Jevon Chandra’s AMSR, ‘The Faraway Nearby’

Jevon Chandra’s AMSR, ‘The Faraway Nearby’

By Jonathan Chan

This is a writer's response to Jevon Chandra’s AMSR. AMSR is an Art & Market project featuring digital and physical small rooms showcasing the practices of emerging artists and writers. For more information, click here.

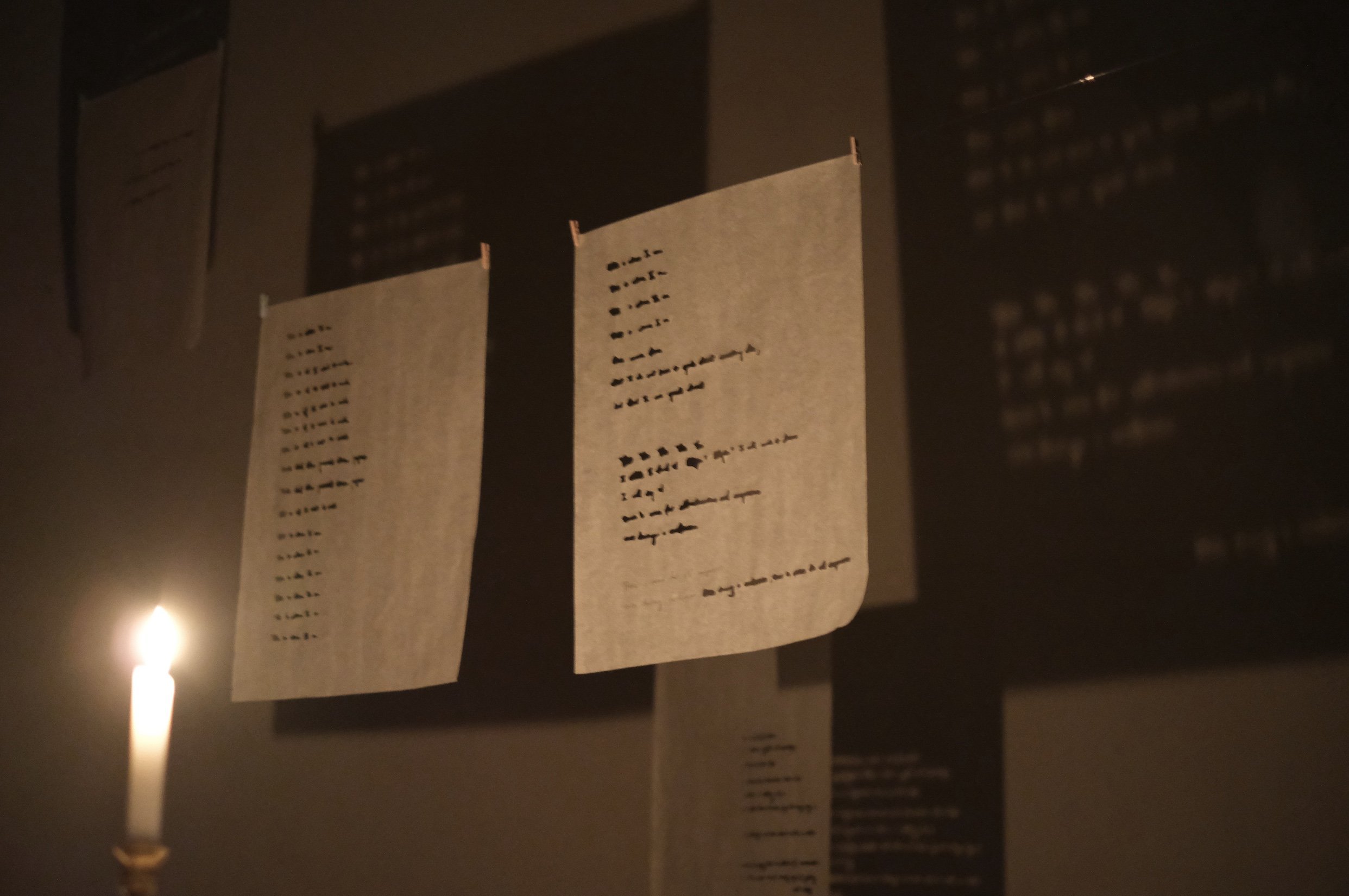

Carved by their edges into sheets of silk paper, the words are a trace, both there and not. They are clipped at the corners, hung by threads. As the pallor of midday fades to night, a candle is lit at the centre of the room. The dark silhouettes etched on translucent paper are made inverse; a sheet of shadow looms, shapes of language letting a flickering gleam through.

Jevon Chandra, ‘Other Things’, 2022, pencil and cut-outs on silk paper, candle, 4-channel sound, paper cut-out: 50 x 37cm; installation dimensions variable. Image courtesy of the artist.

More tentative, more careful is this expression of speech. Language is known both as an absent presence and a present absence, a deferral of legibility, an invitation to examine the contours of what is and what isn’t. Somewhere, along the razor edge of doubt and belief, the artist’s words drift in a still room, known precisely by their lack.

Elsewhere, the words are hammered, nailed to a wooden door. Bodies surround them, swollen and drenched, and they fall:

thud,

thud.

thud.

*

Jevon Chandra, ‘Songs of Companionship #1 and #2’, 2019, laser-cut acrylic, servo motor, die-cut digital print Bristol paper flaps, Arduino, code. Image courtesy of the artist.

Hands, traced in red ink, each reaching across a frame, caress one another. They touch, entwine, thumbs interlocked, move forward, and back. The motion of panels makes it so, one flap after the other. Hands like lace, like the weaving of muslin, tips over texture, tracing curves and wrinkles. Always repeating, leading and following, a dance choreographed in a flurry of paper. Each capsule is a digital copy, code thrumming as the panels recur, hands traced in red, holding, holding. Their clatter like a song, machine like an old instant camera. Hands, feeling, grasping, unclasping, until the flip is switched. The motor’s hum ceases. The capsule is kept in a box, hands in half-release.

*

Peering through the pane of memory, the artist stands in a choir. Their mouths are agape, two girls in dresses of white and red clutch microphones. One has a yellow cord that snakes between small feet, the other is wireless. Beside them are boys, some with red bow ties, one in a t-shirt bearing a cartoon dalmatian. At the side of the choir is a boy in red and white, focus honed on the xylophone laid before him.

Jevon Chandra, ‘This Side of Heaven’, 2022, 4-channel sound, FM radios, dimensions variable. Image courtesy of the artist.

Across the expanse of time sounds a hymn, sung in Bahasa Indonesia, a language of comfort to the artist. It is a translation of a hymn from English. Elvis is said to have made it popular. The artist presents it for us to hear, a single voice stretched without accompaniment. “What happens when we pull that thread? What sustains that? What is distorted?” His questions are laid over a psalm. The children, frozen, are singing, just as the streets begin to tear apart, for a Christian face is often also Chinese.

On the other side of twenty years, Indonesia to Singapore, analogue to digital, the hymn plays:

Jika saya telah melukai jiwa hari ini

Jika saya telah menyebabkan satu kaki untuk pergi

Jika saya telah kehilangan kesengsaraan saya sendiri

Ya Tuhan memaafkan

If I have wounded some poor soul today,

If I have caused one foot to go astray,

If I have walked in my own willful way,

Dear Lord, forgive.

*

Rustle of grass underfoot. Small tree erupting from the earth. The artist feels the island, familiar and not, imagines the lines dissipating from his father’s face, jaw loosened, brow uncreased. Instead, forlorn in this return, he sits by the tombstone, trades old laughter, swallows the distance of an archipelagic dream. The sky is humid, the sky is spotless. One granite cross stands within this plot of land. How poetic, the artist muses with a click of a finger. The whole nation buries its grief. Across the stretch of the Java Sea, the scene is turned into an etching. The texture is awash in navy. It is printed on a canvas of white. See how they sit in remembrance. See how their shoulders almost touch.

Jevon Chandra, Homebound, 2022, line etching, surface print, embossing on Zerkall white paper, paper size 50 x 70cm; image size 17 x 30cm. Image courtesy of the artist.

Jevon Chandra makes no effort to hide. The symbols — sonic, textual, and visual — are laid out for all to see. They are the remnants of an old ecclesial history. In art, a moment can stretch to an eternity. For 24 hours, an installation can bristle against being worn down yet lose no sense of greater meaning. An absence, a loop, a photo, a print: they can all be ciphers for remembering and for moving on, transcendence captured in an instant. Jevon likes to be present, to walk around while talking to people, to turn these experiences over to the idea of psychogeography. How does a landscape, physical and psychic, come into being? How does something affect you? How are you affected?

Embedded in each of his works is the leaping memory of a place: personal scribbles on silk paper in Leipzig, an exhibition by Marina Bay, worship sung in a Bahasa service, a quiet graveyard on Bangka Island. A presence is evidence of an absence, while absence can serve as evidence of a presence. He asks a question of epistemology — how we inch toward not being true but less wrong, somewhere within the warped morass of doubt, conviction, and belief. And he invites us in, asks us to consider how each piece is placed, is framed, how the entirety of an old religious muscle might find itself unsettled. He invites us to see in each image a hint of something lasting.

For more written responses to AMSR, click here.

About the writer

Jonathan Chan is a writer, editor, and graduate student at Yale University. Born in New York to a Malaysian father and South Korean mother, he was raised in Singapore and educated in Cambridge, England. He is interested in questions of faith, identity, and creative expression. His writing has appeared with ‘Quarterly Literary Review Singapore’, ‘Entropy Magazine’, and ‘The Foundationalist’. More of his writing can be found at here.