An Afternoon of Reconciliation

Jevon Chandra’s AMSR, ‘The Faraway Nearby’

By Amar Shahid

This is a writer's response to Jevon Chandra’s AMSR. AMSR is an Art & Market project featuring digital and physical small rooms showcasing the practices of emerging artists and writers. For more information, click here.

Southeast Asia, being a melting pot of uncountable cultural collisions throughout history, is arguably at the very centre of the evolution towards Globalisation. How would the region react? Do we keep our differences? Do we conform to the global narrative?

Jevon Chandra might be the prime example of such an attempt to the answer. As a Jakarta-born ethnic Chinese, Jevon migrated to Singapore in 1997, a tumultuous year for Indonesia, and found himself neither here nor there in terms of cultural belonging. Personal concerns of reconciliation linger heavily in his works.

Faith and doubt are by-products of belonging, of wanting to connect and affirm one’s place in life. Jevon exemplifies this fleeting — yet important — conversation through his works. The executions are often time-based and require multiple sittings in order to be fully appreciated.

His works put forth relevant questions, and invites sharing. They examine patterns, and reward the observant. They long for commitment, and examine the vulnerable.

***

The very nature of his approach put forth the question of how I should proceed with writing my commentaries. How should I add to this? Do I comment or collaborate?

At the end of our video call meetup, I realised that I would have to revisit and reconciliate with my own personal issues regarding faith and doubt. To not do so would be a disservice in appreciating Jevon’s works. To share and relate on such a level would be the best response one could afford. As an art practitioner myself, I certainly would want to see how people reacted to my work, rather than superficially commenting on it.

Jevon’s concern with his educational experience of learning the mother tongue in Singapore contrasted sharply with his early upbringing in Jakarta. I found similar experiences through my experience of learning in Chinese vernacular schools in Malaysia, despite being ethnically Malay. Such a parallel experience clicks instantly, and resonates to the sensitivity of the artist, and the relevance of his concerns.

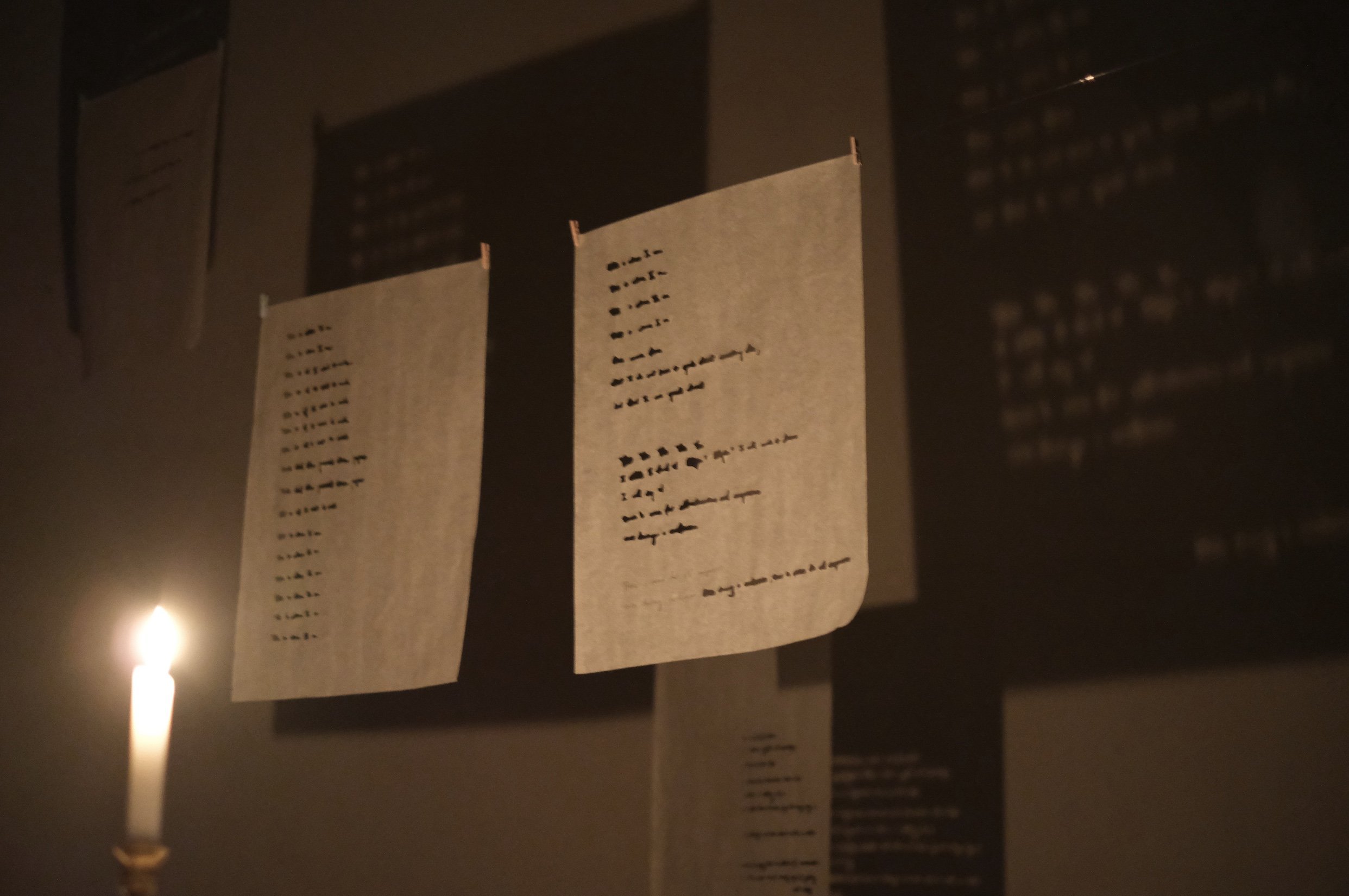

Jevon Chandra, ‘Other Things’, 2022. Images courtesy of the artist.

However, Jevon decided not to confront boldly, but rather to question softly. This is evident in his work ‘Other Things’, where text-like cut-outs on paper are hung, resembling the 95 theses once pinned by the Protestant revolutionary, Martin Luther. The papers are hung and projected with candle lights, as the shadows fall softly on the walls around it. The historical entry point was a strong and powerful one, with questions that linger to this day. Jevon’s treatment, however, does not involve any concrete texts of examination. The mere visual similarities of the two invite insight into our struggle for honesty in our practice, and reconciliation with personal history.

The artist is considerate, and has chosen the path for reconnection rather than confrontation. Such a fleeting method of expression is in itself a perfect vessel for feelings and expression. It suggests a universal question of personal experiences, rather than preaching any concrete ideologies. I found myself attracted to such a proposition, which asserts the finality and the universality of the question. It is not proselytising, and does not force my hand unless I want it to. It does not urge me to bring myself to salvation, or condemn me for what I do not subscribe to.

Jevon Chandra, ‘Songs of Companionship #1 and #2’, 2019, laser-cut acrylic, servo motor, die-cut digital print Bristol paper flaps, Arduino, code. Image courtesy of the artist.

That does not mean that it does not want to speak. The act of candle projection, in itself, signalled the need to communicate and announce. Another analogously animated work, ‘Songs of Companionship #1 and #2’, also speaks to such a need. A looping paper flap animation of hands holding and releasing and holding again, is presented onsite to be examined and appreciated. The robotic nature of the work does not hinder its message. If anything, the rhythmic nature of the sound produced contributes significantly to its immersiveness.

It is ironic that such a connection with Jevon’s work is achieved only through our screens. Current circumstance of the pandemic limited my means towards experiencing the work in person, yet it might as well be that the distance itself had unconsciously created a certain vigilance that enhances our need for connection. Unlike Abramovic’s grandiose and self-idolising display, the artist does not have to be present. It does not demand. It merely asks us to be present instead, which I gladly do.

***

The surreal nature of trying to experience and explain ourselves, arguably, is part of artists’ working narrative. However, I had the privilege of conversing with the artist to understand his personal history. What about audiences that might not have the same luxury? Would this be a hindrance to the whole experience?

Interestingly, the work does not demand it. The connection happens at a cerebral and empathic level, arguably without the need for any prior understanding of its entry points. This is the strength of Jevon’s works: it affords a certain abstract approach. It reminds me on how the need for belonging is inherent in all of us, regardless of previous indoctrination. That is a value that I can certainly get behind.

For more written responses to AMSR, click here.

About the writer

Amar Shahid is a Southeast Asia-based practicing artist, with specialty in linguistics and multi-disciplinary arts. His current work focuses on the intricacies of socio-linguist history with regards to the Southeast Asian social and cultural sphere. Working both in conventional and experimental media, he aims to reflect on the conflicts of cultures and their ecosystems based on his personal anecdotes on the vernacular and conservative educational background of his Malaysian hometown. This clash in values and doctrines shape his works and writings towards a uniquely Southeast Asian narrative.