An Ode to the Monobloc Chair: Symbol of Comfort, Relationships, and Consumerism

Khor Ting Yan’s AMSR, ‘it is light and stackable’

By Elizabeth Low

This is a writer's response to Khor Ting Yan’s AMSR. AMSR is an Art & Market project featuring digital and physical small rooms showcasing the practices of emerging artists and writers. For more information, click here.

There is certainly more to what meets the eye in the mundane spaces that have been carefully captured in Khor Ting Yan’s ‘it is light, but stackable’. They are as quiet and as mysterious as the nostalgic box of old photographs from your grandparent’s attic. Taking what Wikipedia describes as the world’s most common plastic chair, she has carefully placed it against seemingly unexciting spaces and somehow, made this plain and utilitarian object to be a subject of curiosity and quiet allure.

Can the chair be considered a found object in this context? Although she has not physically taken the chair and turned it into a readymade or sculpture, she has heavily adopted its essence in her print works.

In giving life to this ordinary chair and paying tribute to its history and the traces of memories it stores, the artist invites us to pay closer attention to our relationships with people, objects, spaces. The everyday things which we often overlook can sometimes appear to be more meaningful than expected. If we give it a chance, the highlights of life can exist in the mundanity of it too.

“In giving life to this ordinary chair and paying tribute to its history and the traces of memories it stores, the artist invites us to pay closer attention to our relationships with people, objects, spaces. ”

It is red, it is white, it is never out of sight.

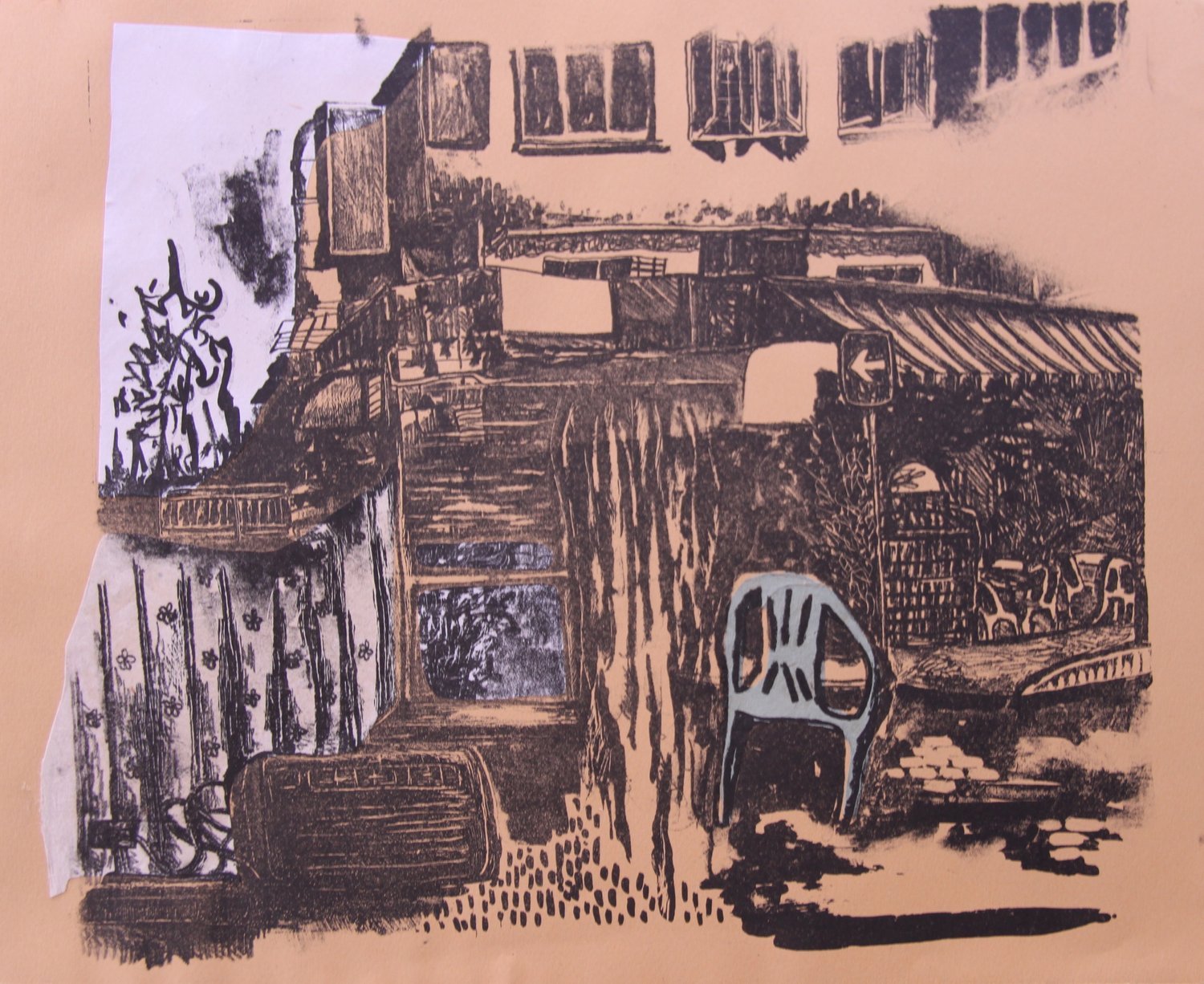

Khor Ting Yan, ‘1 Binjai Park, Singapore 589818 (4/16)’, 2016, lithography with Chine-collé on paper, 36 x 33cm. Image courtesy of the artist.

Although Khor’s artistic journey with the plastic chair began while she was a student in Chicago, her relationship with it ties back to her everyday life in Singapore. Commonly found everywhere and anywhere in red and white, she observed that they exist in environments that are as glaringly contrasting as coffee shops and funeral events.

Yet, despite seeing the plastic chair everywhere, Khor never really saw it as anything beyond one of the many things that existed within the background. However, coming across the familiar object while studying in a foreign country, she was reminded of home. She was conscious that her association with the object differed from most of her peers in Chicago, noting that its presence was more prevalent in Singapore.

The series of lithography prints, ‘1 Binjai Park, Singapore 589818’, features a scene from a coffee shop that the artist grew up walking past every day. Featuring a single chair that is designed with minimal lines to indicate its form, it is contrasted against the elaborate mark-making that make up the structure of the corner coffee shop. Though its position is uncentered within the composition, the character of the chair is highlighted within the busyness of its surroundings.

Khor Ting Yan, ‘1 Binjai Park, Singapore 589818 (Other variations - orange)’, 2016, lithography with Chine-collé on paper, 36 x 33cm. Image courtesy of the artist.

Khor Ting Yan, ‘two chairs, some scribbles and a plant (white)’, 2016, screenprint on paper, 65 x 50cm. Image courtesy of the artist.

On another note, the notion of presence and absence seems evident when comparing ‘1 Binjai Park, Singapore 589818’ and the screen print of ‘two chairs, some scribbles, and a plant’. The former features a single chair, while the latter depicts two. In conversation with the artist, she reflects that the lithography prints potentially captured her longing to be somewhere else amidst the foreignness of Chicago; the single chair represents the loneliness and homesickness she might have felt at the time. However, in ‘two chairs, some scribbles, and a plant’, the presence of newfound relationships in her life were subconsciously highlighted in the second chair. In her subtle suggestions regarding her relationships with the spaces she occupies and the people around her, the chair appears as a symbol of comfort and familiarity.

Does comfort in quantity compromise value in commodity?

Khor Ting Yan, ‘In between Oakbrook and Chinatown’, 2016, lithography on Muslin, quilted, 104 x 140cm. Image courtesy of the artist.

Repetition is visible in the reproduction of the composition ‘1 Binjai Park, Singapore 589818’, and in the imagery printed within individual artworks like ‘my plant is dying’ and ‘in between Oakbrook and Chinatown’. The question at hand is, is this concept of repetition a reflection of the comfort and structure of the familiar? With the artist’s nostalgic and sentimental ties to these spaces, it is not far fetched to assume so. However, the act of repetition goes beyond comfort and into something far more multidimensional.

Khor Ting Yan, Process shot of ‘1 Binjai Park, Singapore 589818’, 2016. Image Courtesy of the artist.

The idea of mass production is not just present in the spirit of the plastic chair, but in Khor’s practice as a printmaker. While the reproduction of prints is a fairly common practice in printmaking, it begs the question of whether reproduced prints are less precious than a unique one? For Khor, the ability to manipulate the image but still reproduce parts of it the same is what excites her as it reflects how she perceives spaces differently with time. In that vein, the reproduction of and the redactions in a series of prints like ‘1 Binjai Park, Singapore 589818’ allows her to look at the same spaces in different ways. Thus, the degree of repetition in the context of Khor’s practice is not about quantity, but in the unique perspectives that each print offers.

Seeing value in the everyday

Like the plastic chair that we so often pass by without a glance, do we take all mass-produced items for granted? Does high supply make something less worthy of our attention? In this consumeristic era, we are often distracted by the frills of material culture accelerated by the market. But if we determine the value of something by its presence in our lives rather than its exclusiveness, we stand to see them in a more appreciative light. This applies to both our surroundings and the people around us.

Through her contemplative depictions towards the more mundane moments and details of our everyday, ‘it is light, but stackable” encourages us to see value in the unexpected. In our fast-paced culture, Khor reminds us that it is worth taking a step back to appreciate the quieter and less refined moments of our day to truly live in the present.

For more written responses to AMSR, click here.

About the writer

Elizabeth Low is an emerging art professional based in Malaysia. She is currently an independent curator and writer who has written professionally for art exhibitions and art festivals. She has an interest in themes of access and inclusion within the Southeast Asian narrative and is a founding member of the new online art platform, In Transit. She holds a MA Degree in Art Management and Curating from Richmond, The American International University in London.