Re: (-producing, -membering, -looking) it is light and stackable

Khor Ting Yan’s AMSR, ‘it is light and stackable’

By Kristi Lim

This is a writer's response to Khor Ting Yan’s AMSR. AMSR is an Art & Market project featuring digital and physical small rooms showcasing the practices of emerging artists and writers. For more information, click here.

“As we grow older, we forget what we need to teach”. Khor Ting Yan made this comment with reference to teaching her primary school students: to place their water holders close to them, peer-critique work with respect and grow through pre-pubescent self-doubt. But there is much that I, too, have been brought to remember and relearn through ‘it is light and stackable’: a showcase of Khor’s work in paper and fabric featuring silent corners, potted plants and plastic chairs. In guiding our attention across scenes typically overlooked as insignificant, her works remind us that the beauty of a thing does not deplete with repetition, and that it is from the smallest moments that our most significant ones bloom.

Khor Ting Yan, ‘my plant is dying’, 2016, monoprint text and screenprint on linen, 366 x 122cm. Image courtesy of the artist.

In her work, two types of repetition bring themselves starkly into view: (1) her thoughtful repetitions of patterns and scenes, rendered in and through varied layers of materials; (2) the motif of the plastic chair, singular in material, factory-reproducible in seconds. A multiplicity of materials, a monobloc chair. Already there is the sense that, transcending the physical singularity of spaces and monobloc chairs, is a non-physical multiplicity. A metaphysical depth to everyday scenes that we encounter through relooking.

Khor Ting Yan, reference photograph for ‘in between oakbrook and chinatown’, 2016. Image courtesy of the artist.

Khor Ting Yan, process shot of ‘in between oakbrook and chinatown’, 2016. Image courtesy of the artist.

With this in view, it is noteworthy to see the diversity of her materials inevitably homogenised and discretised to pixels when rendered in a digital space. I’m reminded loosely of reflections critic Walter Benjamin made in ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’ — that modernity’s love of proximity, coming as close as possible to likeness, kills the uniqueness of a thing, which he describes as an “aura” that one only encounters through distance.

Khor Ting Yan, reference photograph for ‘two chairs, some scribbles and a plant’, 2016. Image courtesy of the artist.

Khor Ting Yan, reference photograph for ‘two chairs, some scribbles and a plant’, 2016. Image courtesy of the artist.

This made listening to Khor reflect on “light” as what animates and transfigures an everyday scene particularly striking. That it is the literal, physical “aura” cast by light that makes each moment of looking unique. Fittingly, these fragile movements of light are captured in delicate chine colle. It is interesting to think of how our flat digital screens, too, emit their own type of light, and what this can mean for the aura of the scenes Khor represents.

Khor Ting Yan, Process shot of ‘1 Binjai Park, Singapore 589818’, 2016. Image Courtesy of the artist.

The intention with which Khor creates moves so contrary to capitalist ethics of monobloc efficiency — to look repeatedly into the life of a thing, and in her words, to “not be afraid to be bored” — that her works give new meaning to repetition, and generate friction on a digital platform slippery with the habit of quick clicks and dispersed attention. In the ‘1 Binjai Park, Singapore 589818‘ series, lithography’s immense tedium is lovingly applied to each iteration of her neighbourhood coffeeshop. I am made more fully aware that even though surfaces can repeat can repeat can repeat, each and every iteration can be dense with the layers of processes labouring to enable them — an awareness that applies to all repetitions, including the code enabling the ctrl+c, ctrl+v used above.

“I am made more fully aware that even though surfaces can repeat can repeat can repeat, each and every iteration can be dense with the layers of processes labouring to enable them — an awareness that applies to all repetitions, including the code enabling the ctrl+c, ctrl+v used above.”

Khor Ting Yan, process shot of ‘1 Binjai Park, Singapore 589818’, 2016. Image courtesy of the artist.

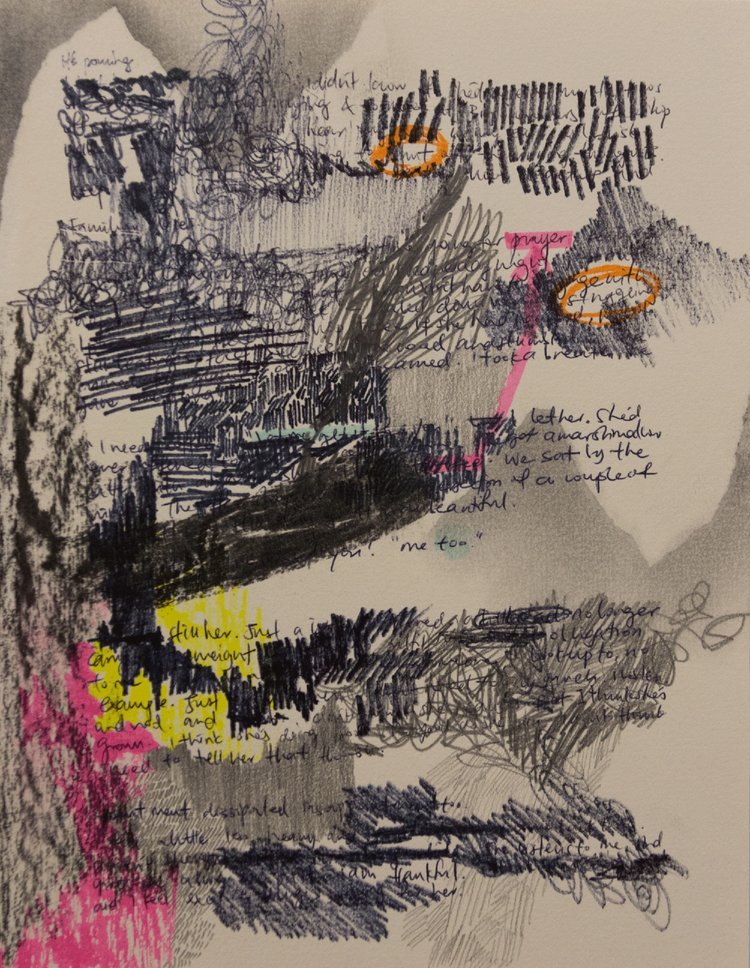

Amidst the patterns and repetitions, ‘two chairs, some scribbles and a plant’ stands out. “I thought you told us not to scribble!” – Khor laughs, imitating a possible reaction her students might have to the print. These scribbles echo a drawing featured on her website, which she describes as a “process piece” – a journal entry, whose text is obscured by fluorescent ink and flowering graphite. The drawing, she says, acknowledges that different individuals have multiple interpretations of a single event. Juxtaposed against the other shapes within the print and in her small room as a whole, these energetic scribbles feel like they tear the work’s representational surface open to interpretation, which we, as viewers, are also invited to participate in.

Khor Ting Yan, drawing. Image taken from the artist’s personal website.

Khor Ting Yan, ‘two chairs, some scribbles and a plant (white)’, 2016, screenprint on paper, 65 x 50cm. Image courtesy of the artist.

The significance of abstraction here feels like it could even apply back to the plastic chair in ‘1 Binjai Park, Singapore 589818”. The slightly abstracted form of the chair, especially when juxtaposed against its relatively representational background, and compared with the chairs in ‘two chairs, some scribbles and a plant’, seems to also invite us to reinterpret it.

The mutability of interpretation reminds me of something else Khor said: that the way we see a single thing can change, not just on account of its external fluctuations, but because we ourselves change internally over time. This brings to light another form of repetition prominent in her work: memory. Khor reflected that her decision to work with fabric in ‘my plant is dying’ and ‘in between oakbrook and chinatown’ had to do with fabric’s durability. Paper appears relatively transient, like its subject: the quickly reproducible plastic chair. Fabric, like a personal memory, lasts.

Khor Ting Yan, ‘my plant is dying’, 2016, monoprint text and screenprint on linen, 366 x 122cm. Image courtesy of the artist.

I think of the interplay between durability and memory in relation to a point thinker Gilles Deleuze once made about stammering and stuttering: that stammering moves forward, makes progress with each repeat, while stuttering stays static, cyclic, unchanged. With each moment of remembering, a memory practices and stutters itself, becoming more durable. But, like stammering, we never repeat remembering in exactly the same way. The repeated patterns in her work, too, are dizzying, kaleidoscopic, dynamic, daring the memory of the scenes she prints to move themselves toward a different conclusion with each iteration.

Khor Ting Yan, ‘in between oakbrook and chinatown’, 2016, lithography on Muslin, quilted, 104 x 140cm. Image courtesy of the artist.

Our interpretations of everyday scenes, and of our memories, change constantly as we ourselves do. I wonder, too, how much of this is retrospective: only after we have seen the most banal, everyday conversations fruit into our most significant friendships and life events do we realise all that sat quietly within them. Khor describes the small snippets of text, transcriptions of conversations, in ‘my plant is dying’ as such: “Really mundane and about nothing in particular, but hinting at bigger issues like relationships, mental health, depression.” I think of these conversations as altering the spaces Khor remembers and reiterates, the way they have in my own memory, my own life.

What does it mean to repeat? In a world saturated with capitalist reproductions, enamoured with novelty, and obsessed with speed, Khor’s small room reminds us to slow down, look and look again at the things that seem most banal, and give our attention to how they never stay the same between moments, constantly changing in ways that can be on account of our own.

—

The shape of the following poem responds to 'two chairs, some scribbles and a plant'. It tries to transcribe, in text, the immutability of the print's bricks, as well as the dynamism, possibility and multiplicity of the patches of light (from the reference photo). Both of these elements respond also to the AMSR's title: light, and stackable — bricks, in place of the chair. I was also interested in expanding on the present continuous "-ing" in the title of Khor's other work, 'my plant is dying'. Death is an event, but all -ings, processes, remain alive. These elements point at time: the sparse text and white space reflect time's spaciousness; the need to give things time if we are to see light move and transform them.

For more written responses to AMSR, click here.

About the writer

Kristi Lim studied comparative literature/linguistics at Cornell University (Class of 2021), where she wrote an opinion column for the school paper, published several poems and played in an experimental music ensemble. She is interested in linear (sound/text) and nonlinear (visual) forms of collage, as mechanisms to retrain perception.