Review of Latiff Mohidin: Pago Pago

Comprehensive show at National Gallery Singapore

By Vivyan Yeo

“you will never understand

the rising of the dawn

between the buffaloes’ legs

cold and stunted

the black waters in the rice fields

reflects in the eyes of the old folks

for centuries”

- Excerpt from ‘You Will Never Understand’ by Latiff Mohidin

Seremban-born Latiff Mohidin wrote the poem ‘You Will Never Understand’ while travelling in Europe. It was composed after he saw Bavarian farmers ploughing with tractors and he speaks of a real sense of tension that exists between people of different cultures. In many ways, ‘Latiff Mohidin: Pago Pago’ at National Gallery Singapore (NGS), curated by Shabbir Hussain Mustafa and Catherine David, comprehensively explores this friction through a wide array of artworks and archival material. Tracking the artist’s journey across Singapore, Europe and Southeast Asia, the survey positions Mohidin as a travelling artist that absorbed a multitude of influences while holding dear the memory of his home village in Negeri Sembilan.

Latiff Mohidin, ‘PROVOKE’, 1965, acrylic on board, 90 x 120 cm. Image courtesy of National Gallery Singapore.

With works created between 1949 and the early 1970s, the presentation narrates the evolution of Mohidin’s renowned Pago-Pago imagery, which is distinguished by its biomorphic forms and pointed shapes resembling fishing boats, shells and stupa-pagodas.

The exhibition succeeds in breaking down the progression of Pago-Pago from beginning to end. “Critics struggled with Latiff’s imagery,” says Mustafa. “They thought that if it was not some kind of abstract expressionism from Germany, then it must be a kind of ‘local’ motif. But the word ‘local’ is insufficient here because Latiff travelled so much.” With this in mind, the NGS survey paints Mohidin in a new light by elaborating on a nuanced set of sources from which the Pago-Pago image was derived. This is effectively done in two ways: by unravelling the artistic networks that Mohidin was embedded in and breaking down both the visual and literary progressions of Pago-Pago.

Latiff Mohidin, detail of a hand-drawn map of Kampong Glam. Image Courtesy of National Gallery Singapore.

‘Latiff Mohidin: Pago Pago’ is productive in using networks as one way of situating the artist in relation to the history of global modernism. It includes an entirely new section with works he made during the 1950s in Singapore. Most notably, it features Mohidin’s hand-drawn map of Kampong Glam as he experienced it, which he produced specially for this show. “I was asked to write something magical,” says Mohidin. “I felt that the map ought to illuminate the sense of joy I felt as a little boy growing up in the area.” This map, as well as an accompanying text soon to be published by NGS, provide vibrant clues as to how he came to know prominent poets and artists such as Abdul Ghani Hamid and Suri Mohyani. Presenting a comprehensive account of his formative years, it uncovers the deep cultural and literary system within Singapore’s Kampong Glam.

The exhibition is enlivened by each segment’s evocative names. For example, the second section, ‘My Fever is Getting Worse,’ details Mohidin’s artistic practice in Europe. Drawing connections to his time in Singapore, the apt title refers to a text he wrote in the 1960s, where he speaks of a fever that followed him from Malaya to Europe and back. This metaphor can be understood as a generative force, or in Mohidin’s words, “the heat of shifting from one media to another and always trying to create something exciting.” He also refers to it as his “encounter with European Modernism and how it simultaneously clashes and fuses with Asian Modernism in Pago Pago.” To further explore this idea, visitors can listen to a speech by Malaysian artist Ismail Zain, who directly inspired the title with his line, “In my entire life, I had never known Latiff without this fever.”

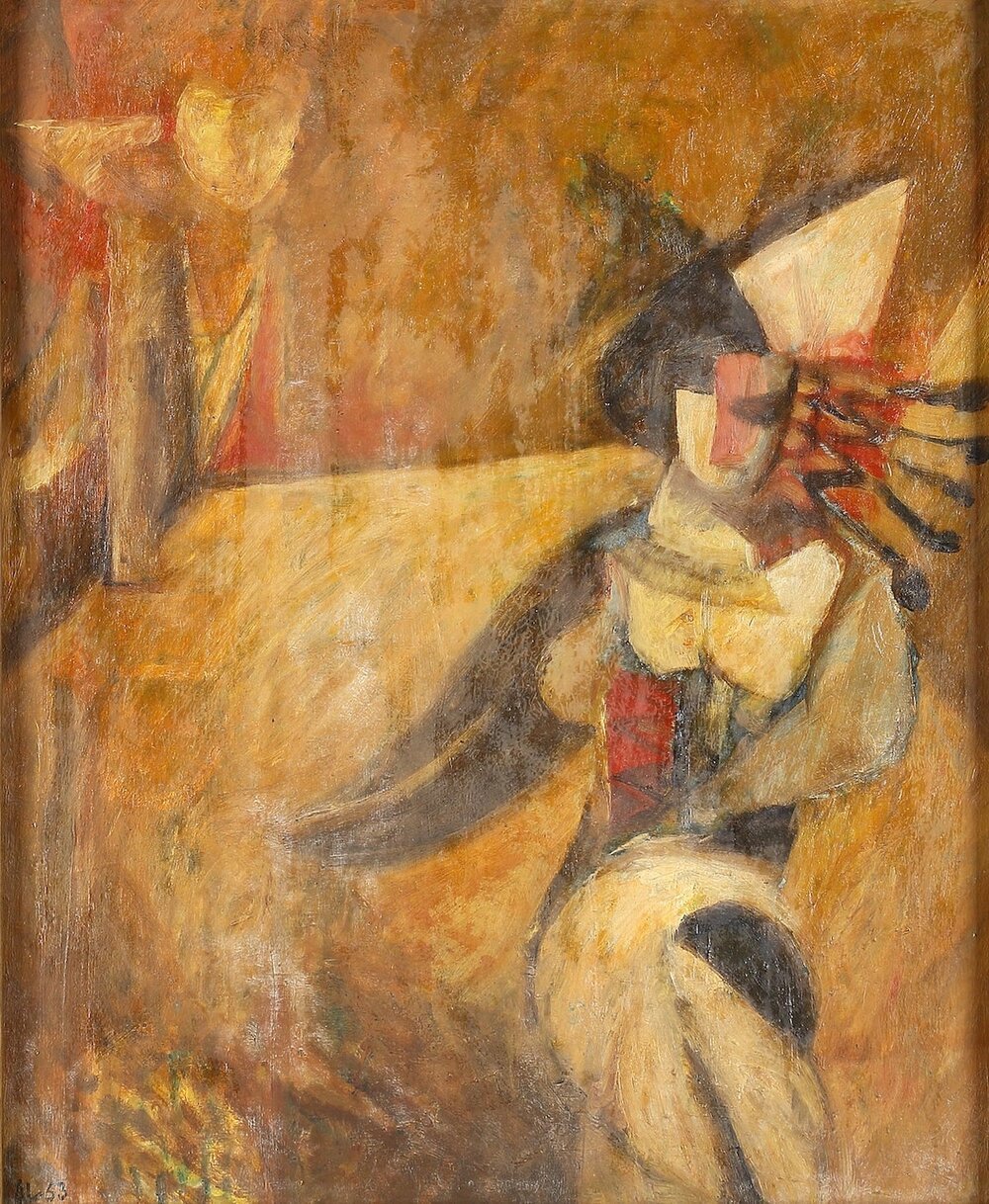

Latiff Mohidin, ‘Circus Dancer’, 1963, oil on masonite board. Image courtesy of National Gallery Singapore.

By displaying a variety of paraphernalia, the NGS exhibition provides an in-depth overview of how the Pago-Pago image grew slowly throughout Mohidin’s travels. “It was not a Eureka moment,” says Mustafa, “but a gradual process.” When seen together, the presentation of newspaper clippings, artist’s sketches and writings help visitors comprehend how living in Berlin exposed Mohidin to a broad range of new material. This consisted of Western paintings, Dadaist artwork, and Khmer artefacts, the last of which inspired his visual use of horns and serrated edges in his portrayal of boats and figures in Berlin.

Another strength of ‘Latiff Mohidin: Pago Pago’ lies in its strategic organisation of visual and written material, which allows visitors a chance to deeply understand Mohidin’s life. One of the exhibition’s most constructive contributions is its timeline, which expounds the artist’s life, influences and significant encounters. It is included at the very beginning of the space and powerfully frames the entire display of works. Because of its high level of detail, however, many visitors might choose not to read the timeline in its entirety. This applies to the selection of paraphernalia as well; the dense information in these materials educate visitors only so far as their curiosity allows.

Installation view of ‘Latiff Mohidin: Pago Pago.’ Image courtesy of National Gallery Singapore.

Expanding from its past iterations at The Centre Pompidou in Paris and ILHAM Gallery in Kuala Lumpur, the NGS exhibition also reveals a lesser-known dimension of the Pago-Pago series through its inclusion of a sculptural work. Sinuous, firm and not easily recognisable, the sculpture reportedly confused critics at the time of its creation. Although it would have been interesting to see more of his three-dimensional works, this solo inclusion is understandable as his sketches and paintings make up most of the Pago-Pago series.

The presentation was also successful in unveiling the literary progression of Pago-Pago alongside its visual forms. It specifically elaborates on what Ismail Zain called a “vernacular cosmopolitanism,” something that Mohidin possessed as an artist and poet. Mohidin could speak German, English and Bahasa Melayu while understanding French and Italian. To illustrate this, the exhibition’s didactic panels emphasise that the term ‘Pago-Pago’ itself was derived from both ‘pagoden’, the German word for pagoda, and the colloquial way of pronouncing ‘pagar pagar’, the supporting structures of Minangkabau architecture in Sumatra. There is a synthesis of cultures that marks Pago Pago as something not entirely Southeast Asian or German, which is contrary to what past critics used to believe.

Latiff Mohidin, ‘Pago Pago II’, 1965, oil on canvas. Image Courtesy of National Gallery Singapore.

‘Latiff Mohidin: Pago Pago’ is an important exhibition for Southeast Asian art history because it exemplifies how categories of art need not be confined to geographical boundaries. Like many artists from the region, Latiff Mohidin created a series that was moulded through his complex interactions with a multiplicity of cultures. Rather than simplifying Mohidin’s journey as ‘Malaysian’ or ‘Southeast Asian’, it is through comprehensive surveys such as this one that museums can constructively add significant artistic practices to the story of global modernism.

‘Latiff Mohidin: Pago Pago’ is open to the public at National Gallery Singapore from 27 March to 27 September 2020. For more information, visit here.