As Above, So Below: Loi Cai Xiang

Bodies mirrored in society for a world in flux

By Deborah Lim

Outside, the world has gone absurd, with science fiction, doomsday prophets and reality converging into one. Yet, this absurdity is framed in silence: the lull of caution in once-frenzied streets; our lips bound by layers that restrict the comfort of speech, breathing and intimacy.

With imposed terms of lockdowns, circuit breakers and movement control orders, we become encased in our spaces. They expand and contract around us, as we so choose. Pressing the eyes shut releases fragments of light, remnants of our refracted views, brilliant against the darkness. Our breath moves within us, natural, heightening with anxiety (and an onset of anxiety is more than common these days).

If we have been convinced to shrink from the touch of others, all we have left is the self, which has been explored through attempts to justify our actions in this time, over-thinking our inner landscapes (“how do you feel” and so forth), a desire for routine and the online or offline documentation of banal activities.

In a pandemic, there is a deeper need to immerse oneself in the arts, which offer consolation, entertainment and the space for imagination. However, the works of an artist that embody these times are difficult to source without seeming contrived; we do not necessarily need antidotes to pain nor should we wallow in suffering. Works of this time require a reality check, a connection with our physical body, sensitivity and, crucially, emotion. They should challenge our placid state, giving rise to room for thought and awareness of the spaciousness within our mind’s eye. Bound in our bodies, we tend to forget the limitless expanse that our brains afford us. Call it what you will: escapism, dreaming, hope or wishful thinking, but let us not underestimate how fulfilling the power of idealism and interconnectedness can be in this present moment.

In such times as these, a phrase playing on repeat, it is important to see that the distinctions between inner and outer spaces, the body and the mind, may not be as far apart as we think. In particular, the comparisons that Hermes Trismegistus drew in his iconic quote hold true: “as above, so below, as within, so without, as the universe, so the soul”.

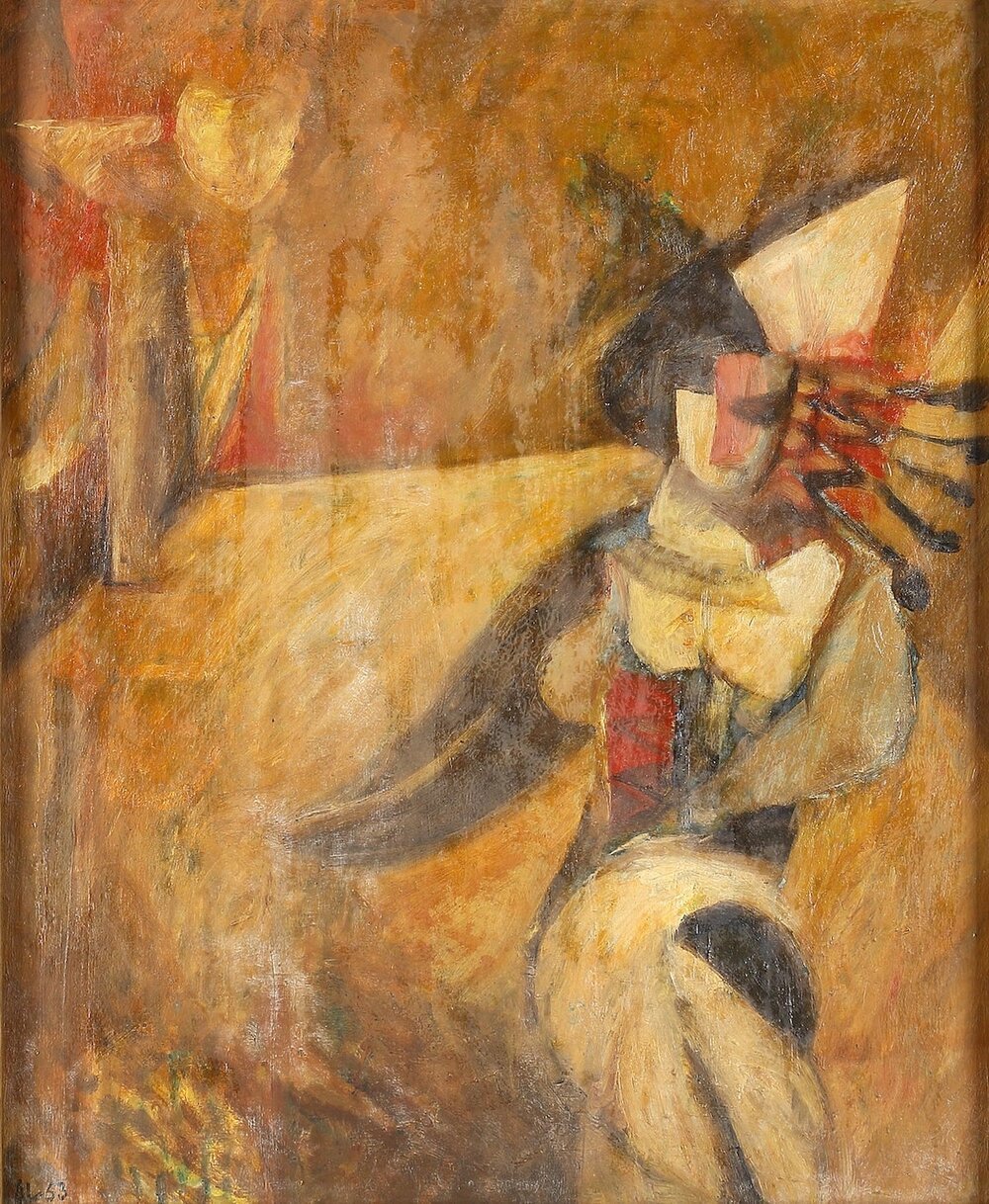

Loi Cai Xiang, 'Constructive Metabolism', 2019, oil on canvas, 102 x 76 cm. Image courtesy of the artist and Chan + Hori Contemporary.

‘Relative Homeostasis’ is an ongoing series of works by Singaporean artist Loi Cai Xiang, the majority of which were featured in his October 2019 solo exhibition at Chan + Hori Contemporary. From the title, we imagine the physical body: muscle twitches, the stinging of an open wound, our foreheads burning up with fever. The sense organs react to information and perceived danger at speeds we cannot comprehend. Homeostasis was once likened to the “wisdom of the body” by Walter B. Cannon, a poetic summary of how our internal system is regulated, stable and constant. It is open, engaging freely with our environment, evolving through processes of destruction and repair. In further bodily comparisons to an accumulation of knowledge, Charles Dickens muses, “there is a wisdom of the head and a wisdom of the heart.”

Aside from titles that point to what is natural and innately human, infrastructure forms the bulk of these artworks. Local landscapes with focal points that are universal and familiar to city dwellers. We observe them daily from our windows, looking outwards at housing blocks, roads and freeways, factories and industrial buildings. They are the blueprints of civilization, and symbolic markers of function and efficiency. One would consider that such hefty structures are built to last – ‘an attempt to make a self-maintaining whole configuration’ – as Christopher Alexander observes. Yet, more often than not, the lives of buildings are as temporary as our own. Like the human body, their parts are similarly built up and torn down, in cycles of regulation and replacement.

(Left) Loi Cai Xiang, 'The Self', 2019, oil on canvas, 61 x 61 cm. Image courtesy of the artist and Chan + Hori Contemporary. (Right) Loi Cai Xiang, 'The World', 2019, oil on canvas, 61 x 61 cm. Image courtesy of the artist and Chan + Hori Contemporary.

Two works, in particular, embody the series. They can be viewed side by side, the first revealing an orb or cracked sphere titled ‘The Self’. This circular structure recurs in Cai Xiang’s works, fragmented layers joined together - a meaty form that could be organic with the fine lines strewn across its surface, or as solid as concrete. It brings to mind the cell, the indication of life at its smallest unit, and us as individuals, with many selves coming together to form a complex ecosystem.

Paired with ‘The Self’ is ‘The World’, a portrait of the artist with his eyes closed, cast in light. In the ancient Greek vision of the ‘kosmos', there exists a harmonious arrangement of parts to form a whole. Both the structures of human beings and the universe parallel each other in possessing ‘elemental body and rational soul’, detailed by Plato. We can thus compare the body to nature, the traces of running rivers that mirror our arteries and veins (volumes of water and blood); as well as the spherical form of the earth, that resembles the shape of our curved skulls.

Loi Cai Xiang, 'Asphyxia', 2016, oil on canvas, 91 x 122 cm. Image courtesy of the artist

With the entire world prostrate at the feet of a virus that we cannot see, links to the Absurd come easily; defined aptly by Albert Camus as a condition arising from the confrontation between rational thought and the ‘unreasonable silence’ of the world. As our familiar structures are overturned, nothing makes sense anymore and this realisation manifests in stress and frustration that consume us.

‘Asphyxia’ is a painting that catapults the burden and weight of tension into the extreme. It appears as an oversized cell or sphere in the heart of the city and a mass of destruction, threatening the structures we build up for productivity and habitation. A literal roadblock manifests as a blood clot in the vessels that supply oxygen to the heart. While the feeling of suffocation is general, we turn to Maslow’s hierarchy to remind ourselves that each person is at the mercy of different needs; and should the need for shelter be fulfilled, the need for love may be left wanting, leaving individuals at staggered levels of distress.

Loi Cai Xiang, 'Homeostasis' (diptych), 2019, oil on canvas, 61 x 91 cm each. Image courtesy of the artist and Chan + Hori Contemporary.

Expanding from its past iterations at The Centre Pompidou in Paris and ILHAM Gallery in Kuala Lumpur, the NGS exhibition also reveals a lesser-known dimension of the Pago-Pago series through its inclusion of a sculptural work. Sinuous, firm and not easily recognisable, the sculpture reportedly confused critics at the time of its creation. Although it would have been interesting to see more of his three-dimensional works, this solo inclusion is understandable as his sketches and paintings make up most of the Pago-Pago series.

The presentation was also successful in unveiling the literary progression of Pago-Pago alongside its visual forms. It specifically elaborates on what Ismail Zain called a “vernacular cosmopolitanism,” something that Mohidin possessed as an artist and poet. Mohidin could speak German, English and Bahasa Melayu while understanding French and Italian. To illustrate this, the exhibition’s didactic panels emphasise that the term ‘Pago-Pago’ itself was derived from both ‘pagoden’, the German word for pagoda, and the colloquial way of pronouncing ‘pagar pagar’, the supporting strExpanding from its past iterations at The Centre Pompidou in Paris and ILHAM Gallery in Kuala Lumpur, the NGS exhibition also reveals a lesser-known dimension of the Pago-Pago series through its inclusion of a sculptural work. Sinuous, firm and not easily recognisable, the sculpture reportedly confused critics at the time of its creation. Although it would have been interesting to see more of his three-dimensional works, this solo inclusion is understandable as his sketches and paintings make up most of the Pago-Pago series.

The presentation was also successful in unveiling the literary progression of Pago-Pago alongside its visual forms. It specifically elaborates on what Ismail Zain called a “vernacular cosmopolitanism,” something that Mohidin possessed as an artist and poet. Mohidin could speak German, English and Bahasa Melayu while understanding French and Italian. To illustrate this, the exhibition’s didactic panels emphasise that the term ‘Pago-Pago’ itself was derived from both ‘pagoden’, the German word for pagoda, and the colloquial way of pronouncing ‘pagar pagar’, the supporting structures of Minangkabau architecture in Sumatra. There is a synthesis of cultures that marks Pago Pago as something not entirely Southeast Asian or German, which is contrary to what past critics used to believe.uctures of Minangkabau architecture in Sumatra. There is a synthesis of cultures that marks Pago Pago as something not entirely Southeast Asian or German, which is contrary to what past critics used to believe.

Loi Cai Xiang, 'Programmed Cell Death', 2019, oil on canvas, 61 x 61 cm. Image courtesy of the artist and Chan + Hori Contemporary.

What is the solution to lift us out of the muck, and into a calmer state of mind? Singaporean poet Marc Nair offers up a line: “we swim towards the shape of safety, drifting against the tides of an uncertain world, grasping life buoys of small mercies”. The keyword here is “we”. While individual needs are different, the absurdity of a world at a standstill is the same. There is safety in the unchanging cycle of humanity: birth, ageing, death. The constant “Programmed Cell Death” takes place as we experience wear and tear, with almost all cells replaced multiple times throughout our lives. Eva Hoffman, noting both “the wisdom of the head and wisdom of the heart” speaks of this passage of time and how cells in our brain and hearts are those that remain unchanged forever.

Returning to the Absurd, it is convenient to suggest that life at this current moment is pointless. It may feel as if suffering is individual, with ‘I’ at the forefront. However, Albert Camus emphasises that with rebellion, read here as the extraction of the self from pity and negativity, suffering can be seen as a collective experience we all face. To combat a mind consumed by the absurdity of it all, the trick is the recognition that this feeling of strangeness is shared by everyone. We need to make sense of the current world realistically, in our own terms, together.

Our interconnectedness goes deeper than we imagine. Carl Jung wrote that dreams unveil primordial or historical ideas that one may not have experienced personally, coupling the rational world of consciousness with that of universal instinct. There is an irony to our dependency, as viruses, our greatest current threat, form about eight percent of the human genome and, contributing to homeostasis, also help to regulate our systems.

Enveloped in our intimate spaces, adapting to new ways of interacting, living and navigating relationships, we should now focus on cultivating the immaterial. Ultimately, it is those that view the universe as a whole and not in isolation, embrace the virtues of others, cherish the details and processes, use the space to dream, ideate and create; and share in actions of love, who will emerge from this crisis as the triumphant ones.

Loi Cai Xiang, ‘Killing Innocence’ (triptych), 2020, oil on canvas, 61 x 61 cm each. Image courtesy of the artist and Chan + Hori Contemporary..

References

Albert Camus: The Madness of Sincerity. 1997. [film] Directed by J. Kent.

Alexander, C., 1979. The Timeless Way Of Building. New York: Oxford University Press.

Cannon, W., 1989. The Wisdom Of The Body. Birmingham, Ala.: Classics of Medicine Library.

Dickens, C., 2016. Hard Times. Macmillan Collector's Library.

Hoffman, E., 2013.Time. New York: Picador.

Jung, C., Henderson, J., Franz, M., Jaffé, A. and Jacobi, J., 1968. Man And His Symbols. Dell Publishing.

Maslow, A., 1943. A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), pp.370-396.

Nair, M., 2020. Performance. [online] Handbook of Daily Movement. Available at: [https://www.handbookofdailymovement.com/performance] [Accessed 16 May 2020].

The Internet Classics Archive. n.d. Philebus By Plato. [online] Available at: [http://classics.mit.edu/Plato/philebus.html] [Accessed 16 May 2020].

Trismegistus, H., 2013. The Emerald Tablet Of Hermes. Merchant Books.

Zimmer, C., 2017. Ancient Viruses Are Buried In Your DNA. [online] The New York Times. Available at: [https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/04/science/ancient-viruses-dna-genome.html] [Accessed 16 May 2020].