Review of 'Awakenings' at National Gallery Singapore

A Window into Art in Society in Asia 1960s-1990s

By Ian Tee

Billboards by United Artists Front of Thailand, exhibition installation view. Image courtesy of National Gallery Singapore.

'Awakenings: Art in Society in Asia 1960s-1990s' makes its final stop at National Gallery Singapore (NGS) after showings in Japan and Korea. The exhibition focuses on the different strategies and socially-charged modes of expression developed by Asian artists during the turbulent postwar years. It is co-organised by the Gallery, the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art Korea (MMCA) and the National Museum of Modern Art Tokyo (MOMAT). In the words of Gallery Director, Dr. Eugene Tan, this partnership "continues the Gallery's trajectory in broadening and deepening the scholarship on the region's post-war art". 'Awakenings' also aims to "critically situate Asia in global art history".

Even though the exhibition is organised into three broad sections, there are many overlapping concerns and approaches: from experimentations with new materials, to interventions in the city, and speaking out about gender issues. One may also loosely categorise the works on a spectrum, from ones that challenge the conventional modes of art-making to others that have a more direct, even didactic relationship to propaganda and activism.

A series of billboards and posters by the United Artists Front of Thailand (UAFT) is a striking example of the latter. Originally displayed in public spaces on Rajadamnern Avenue, they protested against the Thai military regime's support of American intervention in the Vietnam war. It was a site of immense political significance where the 1973 popular uprising toppled the dictatorship of Thanom Kittakachorn, just two years prior. In the exhibition catalogue, senior curator Seng Yu Jin charts the connection between UAFT and Thammasat University, which was a "hotbed for student activism" in the postwar period.

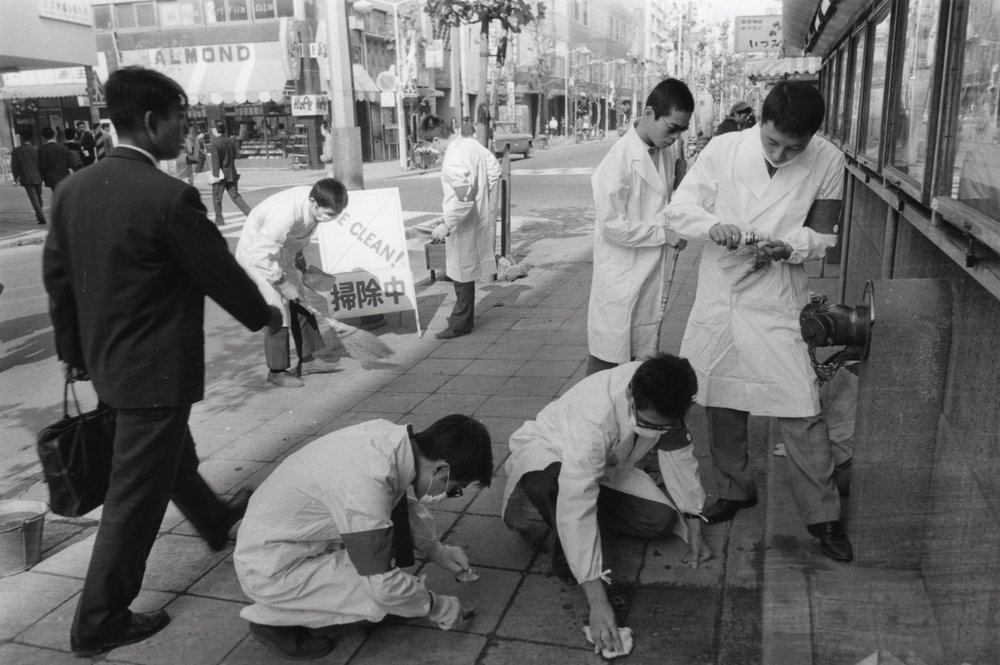

Hirata Minoru, Hi-Red Center’s 'Cleaning Event' (officially known as 'Be Clean! and Campaign to Promote Cleanliness and Order in the Metropolitan Area'), 1964, reprinted in 2018, gelatin silver print on paper, 22 x 33.4 cm. © Minoru Hirata; image courtesy of Taka Ishii Gallery Photography/Film.

Huang Yong Ping, 'Reptiles', 1989, current version remade in 2013, paper pulp, iron and washing machine, 495 x 1300 x 900cm, exhibition installation view. Collection of M+, Hong Kong. Image courtesy of National Gallery Singapore.

However, one need not be confrontational to make a political statement. Hi-Red Centre (HRC) turned to humour in their parody of campaigns initiated by the metropolitan government ahead of the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. The collective took to the streets in white lab coats, armed with cotton balls and toothbrushes for their 'Cleaning Event'. It was an absurd gesture which sought to raise questions about the state's increasing encroachment into public life.

If HRC's performance was one of comic futility, Huang Yong Ping takes the idea of washing for a spin in his show-stopping installation 'Reptiles'. It consists of giant Fujian province tomb structures covered with pulp, made by cycling French and Chinese newspapers in three washing machines. The work speaks to the mixing, cleansing and assimilation of cultures, utilising a paradoxical gesture where the act of cleaning produces an even dirtier result. Aptly, 'Reptiles' was created for one of the first global art exhibitions 'Magician of the World' (1989) at Centre Pompidou, Paris. It was a pivotal moment that not only propelled Huang to international acclaim but also coincided with the Tiananmen Square massacre which led the artist to stay in France.

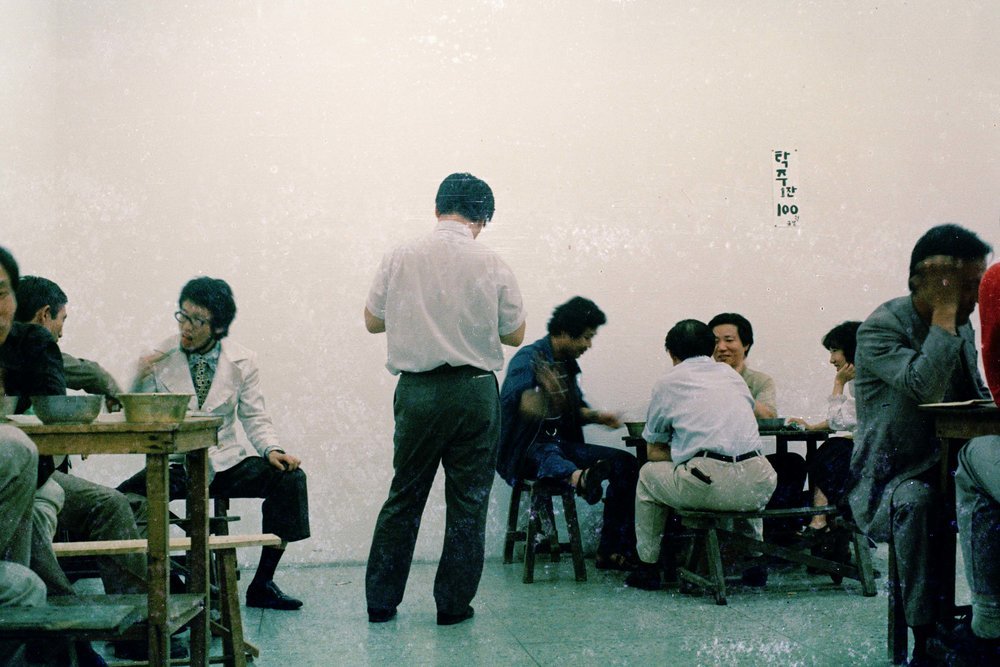

Lee Kang-So, 'Disappearance—Bar in the Gallery', 1973, C-prints on paper, edition 2/10, 6 photographs: 60 x 90 cm (each). Collection of National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea. Documentation of performance at Myeongdong Gallery, Seoul, 25 June 1973. Image courtesy of Lee Kang-So.

Another historically important work on view is Lee Kang-So's 'Disappearance–Bar in the Gallery' (1973), an instance in which a radical gesture in art carried equally profound implications in life. As its title implies, the work transformed Myeongdong Gallery in Seoul into a bar, inviting people to enter and talk freely over food and drinks. It is an early example of relational art, a term coined by Nicolas Bourriaud in 1998. Notably, 'Disappearance' preceded Rirkrit Tiravanija's iconic 'untitled 1990 (pad thai)' by more than two decades. Where Bourriaud's conception of relationality is more utopian in outlook, Lee's piece was a gesture of resistance during a repressive regime that clamped down on congregations of people.

‘Disappearance’ is presented in two guises in the exhibition: as a series of photo documentations from 1973 in the show’s ‘Questioning Structions’ section, and as an installation at a common area between galleries. The setup is activated at selected hours, when visitors can have a meal of local delicacies nasi lemak and nonya kuehs. Markedly, the original context and urgency is lost in this restaging partly due to the advances in communication technology that enable communities to gather in cyberspace.

San Minn, 'Building', 1979, oil on canvas, 61 x 116cm. Collection of National Gallery Singapore. Image courtesy of National Gallery Singapore.

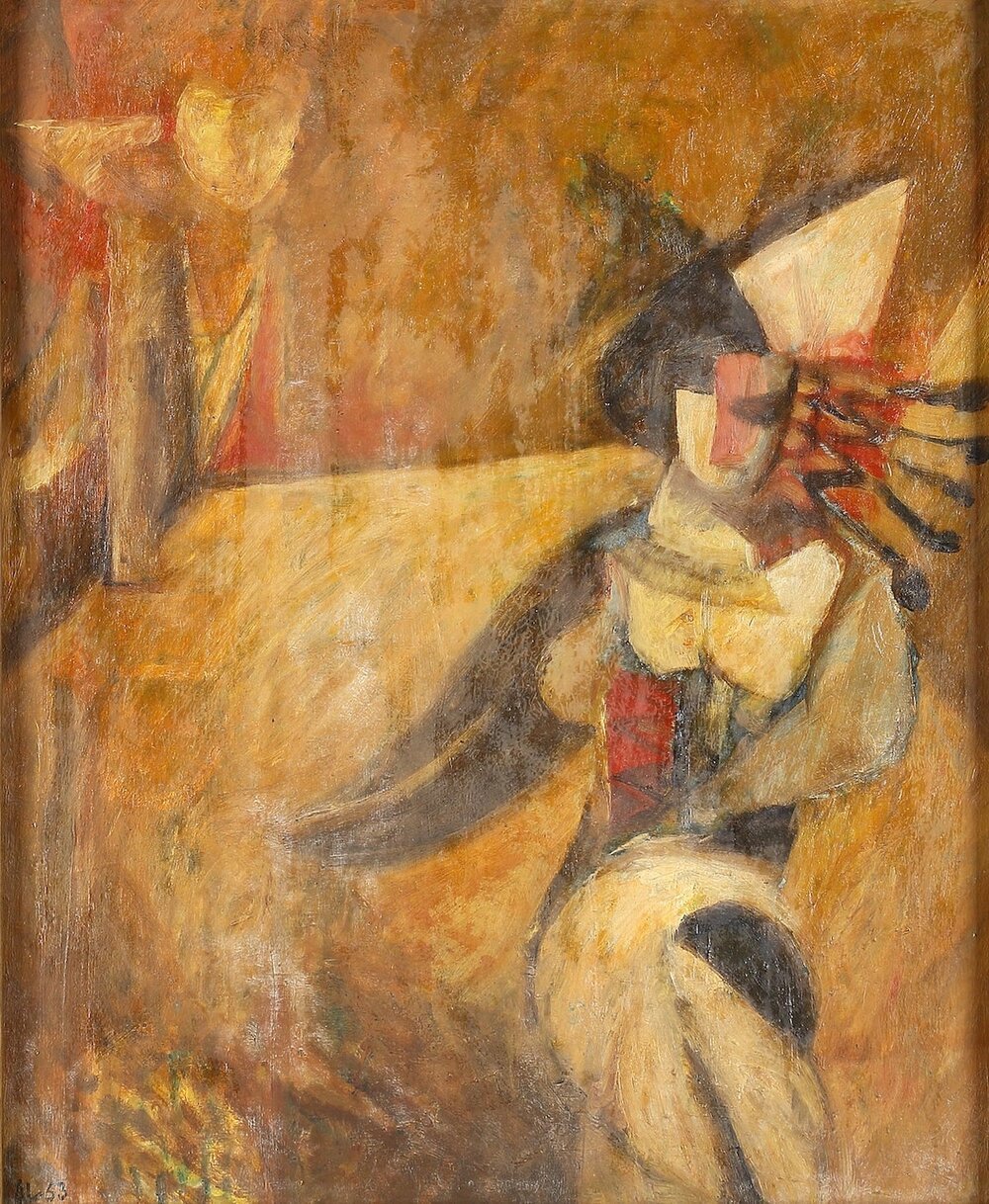

The show closes on a note strikes closer to home. Its final section, titled 'Reinterpreting Histories', is dominated by narrative-based works often laden with social realist tones. Yet, the most potent message is communicated by two works that avoid overt symbolism. Sam Minn's 'Building' depicts a nondescript architecture set against a fiery red sky, the painting's style recalls Cubist experiments with fragmented planes and shapes. What its vague title hides is the fact that the building shown is Insein Prison where the artist was jailed for his participation in the 1974 student protests. This strategy was successful in helping the painting evade censorship in Myanmar, allowing it to be displayed in a group exhibition in 1979.

Similarly, Teo Eng Seng's series of 'D-Cell' — short for detention cell — sculptures deal with the trauma of political prisoners and the pain such incarcerations inflict on their loved ones. In 1987, Singapore's Internal Security Act (ISA) Operation Spectrum arrested 22 individuals without trial for their alleged involvement with a supposed Marxist conspiracy to overthrow the social and political system in Singapore. One of those arrested was the artist's sister Teo Soh Lung, who was kept in solitary confinement for three years. Guided by rough details from their fleeting interactions, these brick-sized clay objects were Teo's attempt at trying to visualise his sister's living conditions.

Largely unknown, 'D-Cell' is the only contemporaneous artwork addressing this black hole in Singapore history. Thus, there is a significant point to be made about its inclusion in 'Awakenings' and its strategic placement in front of 'Building'. The Gallery’s senior curator Adele Tan describes the show as "an act by an institution against forgetting", with the aim of provoking audiences into thinking about issues from the recent past. I find on the bumpy black surfaces of 'D-Cell' a tense discomfort which parallels the effect of art's re-politicisation. It is an unsettling reminder that the artworks on view are not merely artefacts of history, and that the questions they confront are far from resolved.

Siti Adiyati, 'Eceng Gondok Berbungan Emas (Water Hyacinth with Golden Roses)', 1979, remade in 2017, pond, water hyacinths and plastic flowers, dimensions variable. Collection of the artist. Image courtesy of National Gallery Singapore.

Notably, 'Awakenings' geographical distribution leans heavily towards East and Southeast Asia, partly due to collections the show borrows from. Yet it already stands as a mammoth of an exhibition, requiring an investment of time to educate oneself in regional history. This is a tough call for viewers especially when it is easier to appreciate shiny objects and participate in spectacles. But artists are no stranger to making difficult demands, judging by the numerous manifestos written by the UAFT, Indonesian New Arts Movement, Minjung artists and other groups.

If the show's overarching premise is centred on the role of art and artists in society, then by extension, the critical question also applies to public art institutions and their responsibility to content and audiences. Leaving the museum, one comes across Siti Adiyati's 'Eceng Gondok Berbungan Emas' which is a powerful critique of inequality during the Suharto era, artificial golden roses amidst a sea of absolute poverty represented by water hyacinths. Lest we forget, one may also easily envision these golden roses as placeholders for the excesses of art that only serve the intentions of a privileged class.

In celebration of the nation’s 54th birthday and as a venue partner of NDP, the National Gallery Singapore is offering free admission to all exhibitions from now until 12 August, and 50% off tickets from 13 August onwards, including ‘Awakenings: Art in Society and Asia 1960s – 1990s’. This is on view at National Gallery Singapore, from 14 June to 15 September 2019.