With Scars: On ‘Sweet Dreams’ by Ian Tee

First solo exhibition at Yavuz Gallery

By Marcus Yee

Ian Tee, 'EVIDENCE', 2019, acrylic, target paper, collage, song booklet and bandana on destroyed aluminium composite panel, 200 x 150cm. Image courtesy of the artist and Yavuz Gallery.

Ian Tee’s first solo exhibition, ‘Sweet Dreams’ in Yavuz Gallery confronts with its visceral and unsettling emotional geometries. Beyond shock or dismissal, through what other ways can one relate to affectively difficult works of art?

In the seminal essay, ‘From Work to Text’, Roland Barthes wrote, “It is not that the Author may not ‘come back’ in the Text, in his text, but he then does so as a ‘guest’ […] He becomes, as it were, a paper-author: his life is no longer the origin of his fictions but a fiction contributing to his work; there is a reversion of this work on to the life (and no longer the contrary).”

The text, unlike the work, is not “caught in the process of filiation” but “reads without the inscription of the Father”, resonating with his later notion of “the death of the author”. Regardless of the reader’s agency, what if the text is not the temple of polysemic hospitality that Barthes envisioned? How does the play of reading take place amidst dilapidation and ruin, when even authors themselves refuse to return as guests?

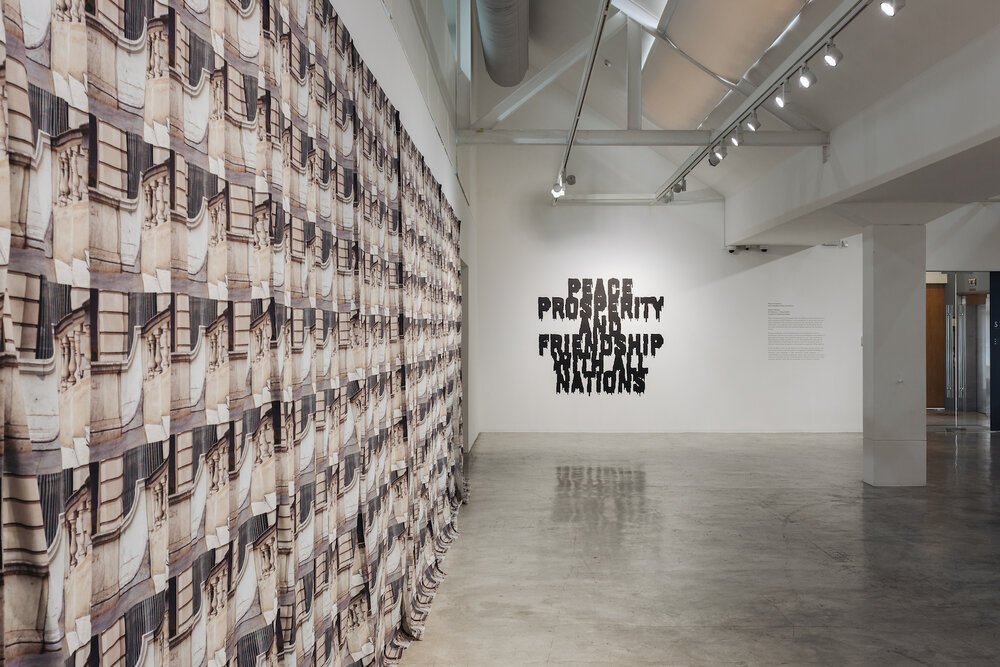

'SWEET DREAMS', 2019, exhibition installation view. Image courtesy of the artist and Yavuz Gallery.

Such is the body of texts, a mutilated corpus, in Ian Tee’s first solo show, ‘Sweet Dreams’, in Yavuz Gallery. Brushstrokes have been seared onto the muddy colour-fields of green-yellows, greys and crimson; they were explosive and desperate in the final hour leading to their failure. They have failed, unlike the crescent-shaped incisions that cut into the aluminium skin. Wounded bodies are strewn across paintings: in one, Kurt Cobain’s cartoon of a hanged soldier; in another, shooting targets torn apart. Another series of works, ‘Fire Blanket’, sees jeans and shirts flayed into its sewing patterns, skinned.

'SWEET DREAMS', 2019, exhibition installation view. Image courtesy of the artist and Yavuz Gallery.

In this gallery of wounds, the sources of violence came to the fore faintly. Assembled onto the aluminium paintings, a bundle of rattan canes and military standard-issue items recall the unsentimental rites of passages— corporal punishment and mandatory military conscription— that initiates individuals into toxic social structures. But such evidences are inert compared to the ongoing violence embedded in the act of seeing itself. Standing passively before pictures of violence, you are complicit in the motors of violence. In one painting, a comic strip from the opening scenes of the X-Men story, ‘God Loves, Man Kills’, depicts two mutant children hunted down by William Stryker’s Purifiers, killing and lynching their bodies onto a swing in an elementary school playground. Pain and spectacle are churned into pleasure and guilt. You become a witness, passing-by, a firer, on standby, aiming your gaze directly at figures on target-papers.

What’s left to read amidst these textual ruins, seemingly oversaturated by scars and overdetermined by pain? How do guests return as guests to inhospitable texts?

Ian Tee, 'YOU POOR SWEET INNOCENT', 2019, acrylic, target paper, comic strips and chain on destroyed aluminium composite panel, 150 x 120 x 5cm. Image courtesy of the artist and Yavuz Gallery.

In her book, ‘Hold It Against Me’, Jennifer Doyle argues against the eschewing of affective difficulty in artworks through controversy or automatic critique relating to identity politics. Instead, Doyle writes, “one actually must look away, and look around”, shifting our gaze from the text to “emotional and identificatory geometries” that surrounds it. Texts are difficult when they demand us “vulnerability, intimacy, and desire”. Following ‘Cruising Utopia’, we could also learn from José Esteban Muñoz’s clarion call for a utopian hermeneutic, a way of reading that finds kernels of futurity in the quotidian and the ornamental, orienting one towards horizons of queerness-to-come and the no-longer-conscious past.

Ian Tee, 'FIRE BLANKET 06', 2019, fibre-glass fire blanket, old clothes, bed sheet, deconstructed backpack, reflective strips and safety straps, 185 x 183cm. Image courtesy of the artist and Yavuz Gallery.

Moments of brittle tenderness are abound in ‘Sweet Dreams’. Even as ‘Fire Blanket’ brings to bear associations of emergency and disaster, feelings of safety, intimacy, and comfort are sewn into the quilt-like compositions. This ambivalence is noted in the exhibition’s title, ‘Sweet Dreams’, borrowing from the Eurythmics’ single, ‘Sweet Dreams (Are Made of This).’ While the title’s overtones of mockery and death are obvious, a trenchant hopefulness lingers on its semantic surface. After all, the hit-song references a lifetime of searching:

“Sweet dreams are made of this

Who am I to disagree?

I travel the world

And the seven seas

Everybody's looking for something”

Later in the song, the bridge makes it clear: “Keep your head up, movin' on/Hold your head up, movin' on.” This turn towards the utopian is not equivalent to unfettered, cruelly naive forms of optimism that drown out other potentialities in memory, mourning, and trauma. It is not the avoidance of scars, as attested by the difficult articulations and silences in ‘Sweet Dreams’. It is also not necessarily about healing. Recalling Muñoz, the project of queer futurity is “a backward glance that enacts a future vision”.

Ian Tee, 'MAN AGAINST MAN, 2019, acrylic, target paper, comic strips and handheld mirror on destroyed aluminium composite panel, 120 x 90cm. Image courtesy of the artist and Yavuz Gallery.

More importantly, the gallery of wounds is not private, or privatised, belonging neither to the artist nor any other individual. This pain is intersubjective, it confronts you, nominating you to tarry along with it. On the bottom left of the painting, ‘Man Against Man’, a military-issued mirror is mounted on another comic strip in the same X-Men story. In this scene, Wolverine reflects in a conversation with Magneto, “But if we use our foes’ methods, my friend... How then are we better than they?” As you find yourself in the mirror, you are interpellated by the text, no longer the unmoved spectator and voyeur, you become a witness and ally, you are not alone with these scars, which are no longer shrouded by shame, instead, they become transports of collective temporal distortion, as we ride together towards the horizon’s warm illumination.

Ian Tee’s ‘Sweet Dreams’ runs from 2 March to 14 March 2019 in Yavuz Gallery.