‘Staggered Observations of a Coast’ at STPI

Charles Lim Yi Yong examines land reclamation in Singapore

By Vivyan Yeo

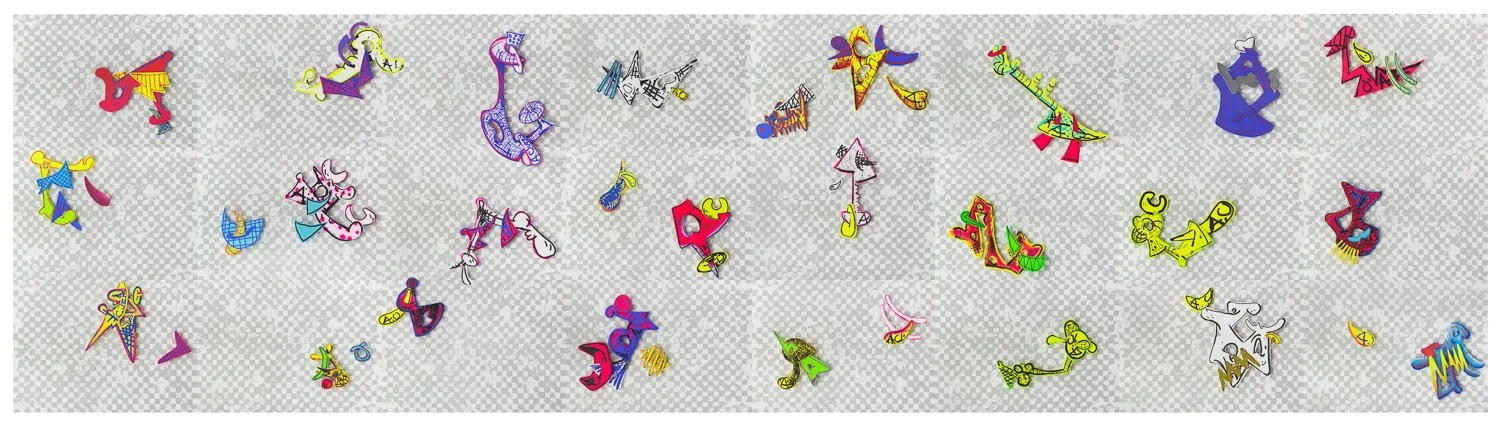

Charles Lim Yi Yong, ‘SEASTATE 9 : Pulau Satuasviewdamartekongmarinajurongcovebranibaratchangilautekongsajahatsenanghantupunggolsebaraokeastsamalunbukomsento’, 2021, laser cut STPI handmade paper, 45.2 x 64.8 x 0.95cm, edition of 2. © Charles Lim / STPI. Image courtesy of the artist and STPI.

The idea of seeing the invisible frames ‘Staggered Observations of a Coast’, a solo show by Singaporean artist Charles Lim Yi Yong at STPI - Creative Workshop & Gallery. The exhibition is a continuation of Lim’s expansive SEA STATE project, initiated in 2005 to reassess the roles of the sea and land in the city-state of Singapore. As hinted by its title, ‘Staggered Observations of a Coast’ values understanding details in an instinctive manner, rather than through a planned or chronological approach. While Lim is more known for his audiovisual works, this exhibition at STPI boasts a wide range of mediums, including magnetic rubber sheets, monotype on paper and sand.

With such diversity in medium and focus on instinctive observation, we might imagine the show to be visually spontaneous and unsystematic. Instead, Lim’s works take on a distinctly sanitised appearance. This cleanliness is not without irony. Upon closer inspection, his works reveal a playfulness that is critical of pertinent subjects such as land reclamation, the boundaries of our nation state, and life at sea.

Lim’s humour can be seen in the series ‘SEASTATE 9 : Pulau’ (2021), a set of 6 laser-cut STPI handmade paper depicting land masses. Embodying a grid system that reminds us of nautical maps, these lands appear purposeful and planned. Each piece, however, is actually an amalgamation of random areas of reclaimed land. Although presented in different shapes, they each take up the same land size in an arbitrary manner. They appear small and movable, similar to toys one can arrange at will.

The arbitrary quality of these works is emphasised in their titles, which are composites of various island names. Take for example the work titled ‘Tekongsajahatsenanghantupunggolsebaraokeastsamalunbukomsentosatuasviewdamartekongmarinajurongcovebranibaratchangilau’. Through satire, we are reminded of the many islands in Southeast Asia that have been modified or lost due to land reclamation. Much like these unblemished maps, the cultures and histories of people who used to live on those islands are wiped clean.

Charles Lim Yi Yong, ’SEASTATE 7 : sand print (400,000 sqm, 2015, Tuas)’, 2021, sand on STPI casted paper, 88 x 65 x 11.7cm. © Charles Lim Yi Yong / STPI. Image courtesy of the Artist and STPI.

Charles Lim Yi Yong, ‘SEASTATE 7 : negative print’, 2021, 3D printed PLA plastic, 93.6 x 66 x 13cm. © Charles Lim Yi Yong / STPI. Image courtesy of the Artist and STPI.

A similar sense of wit exists in ‘SEASTATE 7 : sand print (400,000 sqm, 2015, Tuas)’ (2021), a sculpture reminiscent of a sandbox in a playground. While the work may bring about ideas of creativity and play, our perceptions are soon thwarted when we see its cast on the opposite wall. Immediately, the sculpture, which is actually a replica of the reclaimed area in Tuas, seems artificially made.

Lim's presentation of investigative research through play gives the works unexpected gravitas. They draw attention to how land reclamation is in many ways arbitrary, but also has serious consequences. On the one hand, because this area of Tuas has not undergone proclamation by the Singapore president, the land is still officially part of the sea; it hence exists in a comical and absurd in-between state. On the other hand, we recall that such reclamation of land developed Tuas into an industrial hub. In line with this goal, residents of the island were moved out of their homes in the 1970s. Instead of an area of residence, Tuas is predominantly known today as a heavy industrial area.

Charles Lim Yi Yong, ’Staggered Observations 12’, 2021, monotype on paper, 40 x 52cm. © Charles Lim / STPI. Image courtesy of the Artist and STPI.

Alongside the more conceptual pieces, Lim’s solo exhibition also houses works with refreshing sincerity. His series ‘Staggered Observations’ (2021), and ‘Zone of Convergence’ (2021), honour the practice of understanding our environment through direct experience. For about six months, Lim sailed along Singapore’s east coast. He observed patterns in the waves and clouds, taking note of their changes over a period of time. These observations went beyond the visual to include more tactile components such as taste and feeling. Much like how we learn as children, the monotype prints in ‘Staggered Observations’ encapsulate instinctual responses to our immediate world. In them, we see both realistic and abstract impressions of clouds, the ocean, wind, and elements that might otherwise be invisible to our eyes.

Charles Lim Yi Yong, ‘Zone of Convergence 25’, 2021, collagraph on paper, 31 x 43cm. © Charles Lim Yi Yong / STPI. Image courtesy of the Artist and STPI.

While ‘Zones of Convergence’ adopts a similar technique of making staggered observations, the works in this series assume subtler strokes and paler tones. Its title references a phenomenon known as wind doldrums, where monotonous weather is caused by the convergence of northeast and southeast trade winds. This supposed state of nothingness is thus ironically formed by great forces. The works in ‘Zones of Convergence’ similarly present a tension between serenity and chaos. Within their calm exterior, we find tumultuous waves of movement.

Lim explained that we may find parallels between wind doldrums and the formation of Singapore’s nation state, which is generally believed to have started off on a clean slate. What, after all, was this island before the arrival of Sir Stamford Raffles in 1819? With the large amount of work put into the creation of our history books and in the maintenance of national monuments, most of us do not think of looking too far back.

Charles Lim Yi Yong, ‘SEASTATE 8 : the grid, whatever wherever whenever’, 2021, screenprint on paper, magnetic rubber sheets, dimensions variable, edition of 3. © Charles Lim Yi Yong/STPI. Exhibition installation image at Singapore Art Museum’s Wikicliki: Collecting Habits on an Earth Filled with Smartphones (2021), first presented as ‘SEA STATE 8: the grid’.

The most striking work in the exhibition is ‘SEASTATE 8 : the grid, whatever wherever whenever’ (2014-2021), which highlights the fluid existence of the ocean. Taking the form of magnetic rubber sheets stuck onto a wall with magnetic paint, the work illustrates a nautical map of Singapore. One large piece represents the nation state, while multiple other pieces symbolise the sea state, which can be broken apart and scattered throughout the white wall. This creates a divide between the familiar and whole island of Singapore, and the unknowable, uncertain nature of the sea. In many ways, the ocean seems like a blank slate; its boundaries constantly shift according to our plans for land reclamation.

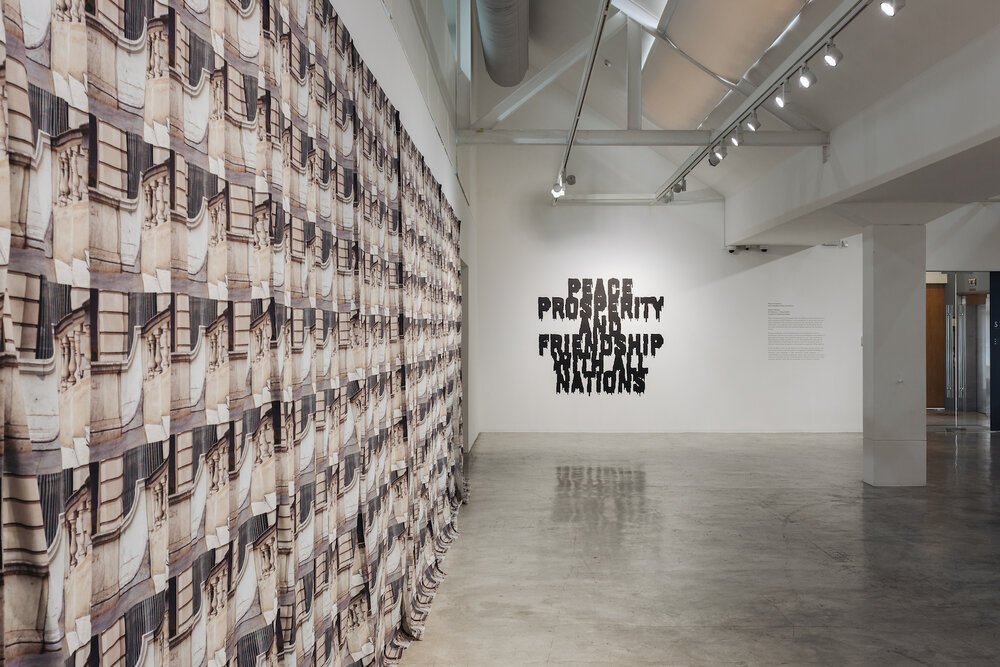

Exhibition view of ‘Charles Lim Yi Yong: Staggered Observations of a Coast’, 2021. Image courtesy of STPI – Creative Workshop & Gallery, Singapore.

Exhibition view of ‘Charles Lim Yi Yong: Staggered Observations of a Coast’, 2021. Image courtesy of STPI – Creative Workshop & Gallery, Singapore.

Likewise adopting a grid pattern is the introductory wall text of ‘Staggered Observations of a Coast’. When entering the exhibition, visitors are encouraged to take a blue or white square sticker. After walking through the show, they can then write their own observations on the sticker and paste it on the grid within the introductory wall. This participatory element invites audiences to reframe the ways they look at the sea and land. While we may be used to checking digital applications for the weather and navigation, perhaps we could try to recognise our surroundings for what they are.

“As a whole, the exhibition prods us to see the invisible, not only in terms of natural phenomena but also in the background forces that mould our understanding of home. ”

With the issue of land reclamation in particular, we largely acknowledge it as a beneficial asset to Singapore in the realms of development and urbanisation. The more invisible effects, however, are in the many communities that had to give up their homes, the islands that have disappeared and the damage it has done to marine life. Through becoming aware of the gaps in our knowledge, we can strive to see important concerns that often go unnoticed, and take action.

'Charles Lim Yi Yong: Staggered Observations of a Coast' is on view from17 December 2021 to 30 January 2022 at STPI Gallery.

In conjunction with the show, STPI Gallery has organised a line-up of programmes that aim to provide a multitude of perspectives in thinking about the development of Singapore. For more information, click here.