Review of 2019 Asian Art Biennial

‘The Strangers from Beyond the Mountain and the Sea’

By Sara Lau and Ho See Wah

Ting Chaong-Wen, ‘Virgin Land’, 2019, tempered glass floor, ultraviolet light tube, neon lamp, raw material of cinchona tree, tonic water, multi-channel video, dimensions variable, exhibition installation view. Image courtesy of 2019 Asian Art Biennial.

Sara: So we’re in Taichung to see the 7th Asian Art Biennial at the National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts. It’s curated by artists Ho Tzu Nyen and Hsu Chia-Wei, from Singapore and Taiwan respectively.

See Wah: Yes, the title of this Biennial is ‘The Strangers from Beyond the Mountain and the Sea’. It’s a poetic way of expressing what the curators are doing: bringing in peripheral and decentralised ways of looking at relevant issues in our world today. For example, the post-Anthropocene, rapid technological revolution, and the ecological crisis. And I love the curatorial diagram. It’s a nice visualisation of the ideas they are exploring.

The Exhibition Diagram of 2019 Asian Art Biennial.

S: It’s definitely refreshing, especially since many contemporary art exhibitions rely on text to explain concepts. This is not inherently wrong, but sometimes the text seem to take precedence over the art.

The curators reference James Scott’s ‘The Art of Not Being Governed’ and Bruno Latour’s ‘We Have Never Been Modern’, both of which present alternatives to modern industrial capitalism. The show is conceptually strong, and I love the title of the show. This year’s Biennial highlights the relationship between East Asia and Southeast Asia, where “mountain” and “sea” are two important geographical elements, especially in Taiwan. It conveys to the audience that where the Biennial is situated is intentional and important.

SW: Thinking about geography is interesting in light of the ‘Out of Taiwan’ theory, which was first proposed by archaeologist Peter Bellwood in the 1980s. It posits that the Austronesian language, and the people who speak it, came from Taiwan tens of thousands of years ago. From this perspective, we’re able to see the overlapping cosmologies and histories across national boundaries more clearly.

Exhibition installation view. Image courtesy of 2019 Asian Art Biennial.

SW: We just came out of the Biennial after three hours, and I think the exhibition has met our expectations to some extent.

S: Yes, that's fair to say. Not all the artworks fit perfectly into the conceptual framework. Even so, it was still cohesive overall.

Researcher’s footnotes at 2019 Asian Art Biennial.

S: We both liked researcher’s footnotes, which are short and digestible components of information that help to contextualise the artworks. They are included in every gallery, with each idea or subject matter explained in a paragraph, accompanied by images and quotes from relevant texts. The reference materials are available for browsing display as well.

SW: Yes, just because there are usually so many ideas being surfaced in a biennial, so sometimes it can seem like there are many loose strands. The footnotes help to tether the artworks to the framework of the show.

Antariksa, ‘Co-Prosperity #4’, 2019, UV-sensitive ink on paper, A4-sized copies (amounts variable), UV light. Image courtesy of 2019 Asian Art Biennial.

S: Moving on to the works themselves, one that stood out to me is Antariksa’s ‘Co-Prosperity #4’. It was a dark room with UV lights and there are sheets of paper with biographies of Japanese intellectuals who worked with the Japanese military’s propaganda department in the 1930s to 1940s. The audience is are encouraged to take these papers, but because they’re UV sensitive, the information is confined to that room. It perfectly represents how certain histories are deliberately hidden, and the gatekeeping of knowledge on a broader scale. I saw a visitor that took one of every sheet of paper, but returned them once she realised she couldn’t read them in regular lighting. It’s a simple but clever idea.

SW: For me, I enjoyed both of Ming Wong’s works in this show. I’ve always been a fan of his videos, because they’re ironically funny and entertaining while sending his messages across strongly.

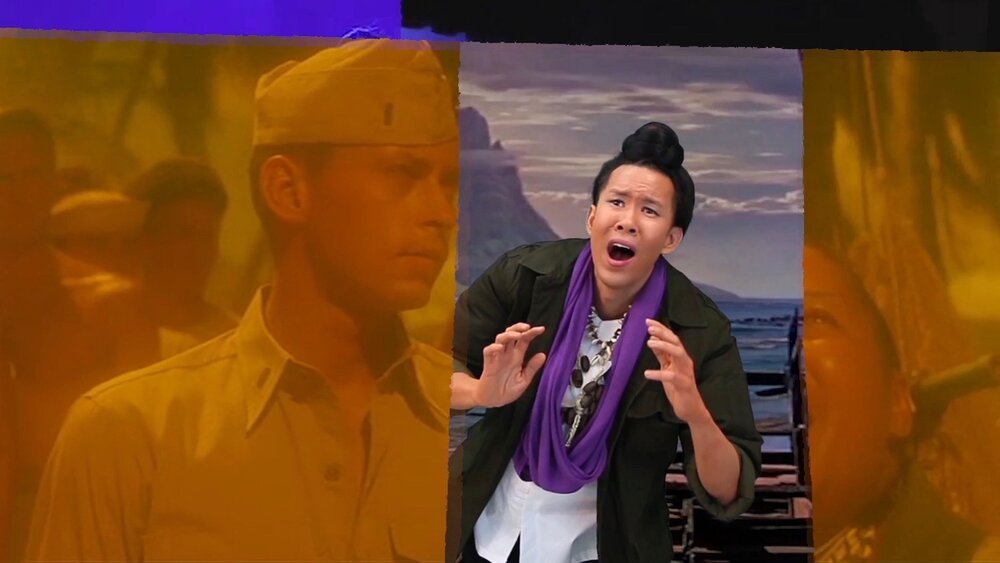

Ming Wong, ‘Bloody Marys – Song of the South Seas’, 2018, mixed media installation featuring a single channel HD video with stereo sound and archival material, 10 min 35 sec. Image courtesy of 2019 Asian Art Biennial.

S: What I appreciated most about ‘Bloody Marys – Song of the South Seas’, is that the aesthetic and form are well-integrated with the concept. By playing the character of Bloody Mary in this musical, he is criticising colonial histories and imagery in an irreverent and satirical way. It’s commenting on the savagery of the pleasure that they took… you know, they turn it into a farce, into a musical, and this is him tossing the ridicule back at them. It seems to have been influenced by meme culture and post-internet aesthetics as well, which I enjoy. It’s a nice break from all the long-form film installations.

SW: It has wonderful entertainment value as well! It’s amusing to take in, and the song is quite catchy! At the same time, you know he’s mocking it, so that makes it even more fun. It’s that extreme self-reflexivity that I enjoy about his works. As for his other video, ‘Tales of the Bamboo Spaceship’, there’s a portion where the artist spliced moments from old Chinese movies and collages them. Below that, he adds his own subtitles such as “Witch”, “Ladyboy” and “Male/Female Impersonator”.

Ming Wong, ‘Tales of the Bamboo Spaceship’, 2019, single channel HD video with audio. Exhibition installation view.

It may not seem like much, but when he “intrudes” with his own quips, you’re made to think about what it means instead of taking it at face value. After all, cinematic history reflects certain cultural values and ideas, but only those that the propagator wants people to see. Ming Wong jibes right at that and asking you to question what it means in the real world.

S: Yes, the show itself is quite depressing, but he reflected on a heavy topic in such a light-hearted way. It’s not that he’s disregarding the seriousness of the issue but he’s saying, hey, we can have a little bit of fun with it, and we can think about how to move on from there. The work offers new possibilities for reconciliation and fills that void the curators talk about.

SW: It makes us think about how we can reclaim back this kind of power through other possibilities.

S: I think we are bombarded by bad news every single day. We know things are not great right now. This has been something that has been brought up by other artists as well – there needs to be some element of hope. It’s easier to give up and say the world is terrible, but how do you project a future that you want, you know? Even if it doesn’t materialise, that kind of “being” is so important.

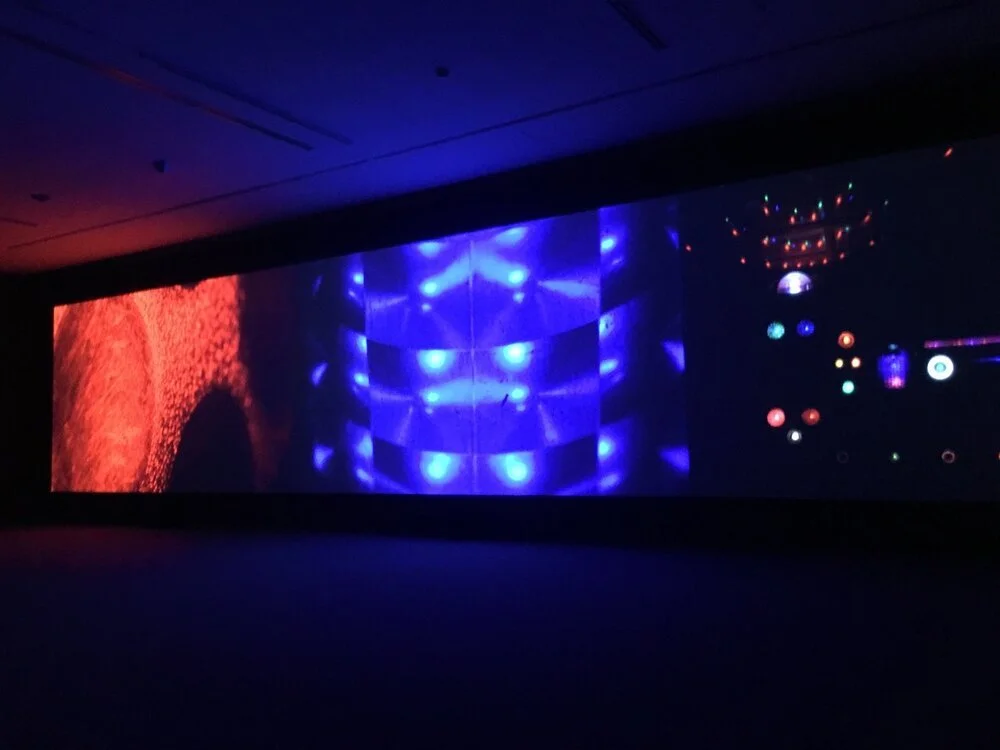

Liu Chuang, ‘Bitcoin Mining and Field Recordings of Ethnic Minorities’, 2018, three-channel video, 4k, 5.1 sound, 40 min. Image courtesy of 2019 Asian Art Biennial.

SW: Another work that I loved – as do you – is by Chinese artist Liu Chuang, titled ‘Bitcoin Mining and Field Recordings of Ethnic Minorities’. The artist weaves together the current contemporary situations and networks of bitcoin mining and the Zomia highlanders in his three-channel video.

S: Yes. At first, I didn’t see how bitcoin mining could be related to field recordings of ethnic minorities. Watching the film felt like a revelation. It perfectly encapsulated the curatorial diagram – your brain starts to make all these connections between the ideas presented through the film’s imagery.

SW: It hits the mark on so many levels. For example, the film elucidates how the state attempts to control these highland minorities, the “strangers from beyond the mountain”, to exploit the abundant resources on their lands for bitcoin mining. Liu highlights a particular aspect of this control: through assimilating them into mainstream digital culture.

At one point, all three screens were showing bright, flashing lights from a home entertainment system, and the experience was intensified with the accompanying blaring music. It overloads you with a ferocity of control. We see for ourselves the relentless impact of the fourth industrial revolution.

Liu Chuang, ‘Bitcoin Mining and Field Recordings of Ethnic Minorities’, 2018, three-channel video, 4k, 5.1 sound, 40 min. Exhibition installation view.

S: It’s a certain kind of violence. It’s hypnotic, almost like you’re about to be brain-washed. I think the film is balanced though, because on the flipside, it also emphasises how bitcoin initially emerged as a decentralised monetary system.

SW: It is. As compared to a state-sanctioned form of currency. At the same time, the film also shows how the bitcoin world relies on these state infrastructures.

S: Yes, on abandoned infrastructures, like those automated mining spaces within Zomia, near places where electricity can be generated through dams and windmills.

SW: It’s an interesting symbiotic relationship. These spaces are re-appropriated, yet these alternative networks are still embedded within the structures that they are trying to distance themselves from.

S: There's no real way to escape the world. You are embedded in a network one way or the other. It's more about how to subvert it. The highlanders are using these resources that have been abandoned, and it’s really them asserting themselves, even if they are putting themselves back into a world they're trying to escape from.

SW: It does end on a sombre note. The concluding footage was of Queen Amidala from Star Wars morphing into ethnic minority women from various cultures which her costumes were inspired by, or taken from. It feels like a violent moment. Star Wars is such a popular franchise, and most people would recognise her even if they haven’t watched it. Yet, I don’t think the origin of her costumes is popular knowledge, so it was almost painful to have this invisibility of the already disenfranchised demonstrated on screen.

S: I can see that. The way I interpret it is a little more optimistic. Maybe the filmmaker is also trying to suggest that this is the future. The fact that an American futuristic film franchise took all these examples, means this form has something of value. It's bringing what people might consider as history into the future, asserting that this will always continue to exist. Of course representation is important as well, and I don't deny that this was what the filmmaker was trying to do.

SW: And that’s the great thing about art. It allows us to think about various possibilities, and not constrain ourselves to one singular viewpoint.

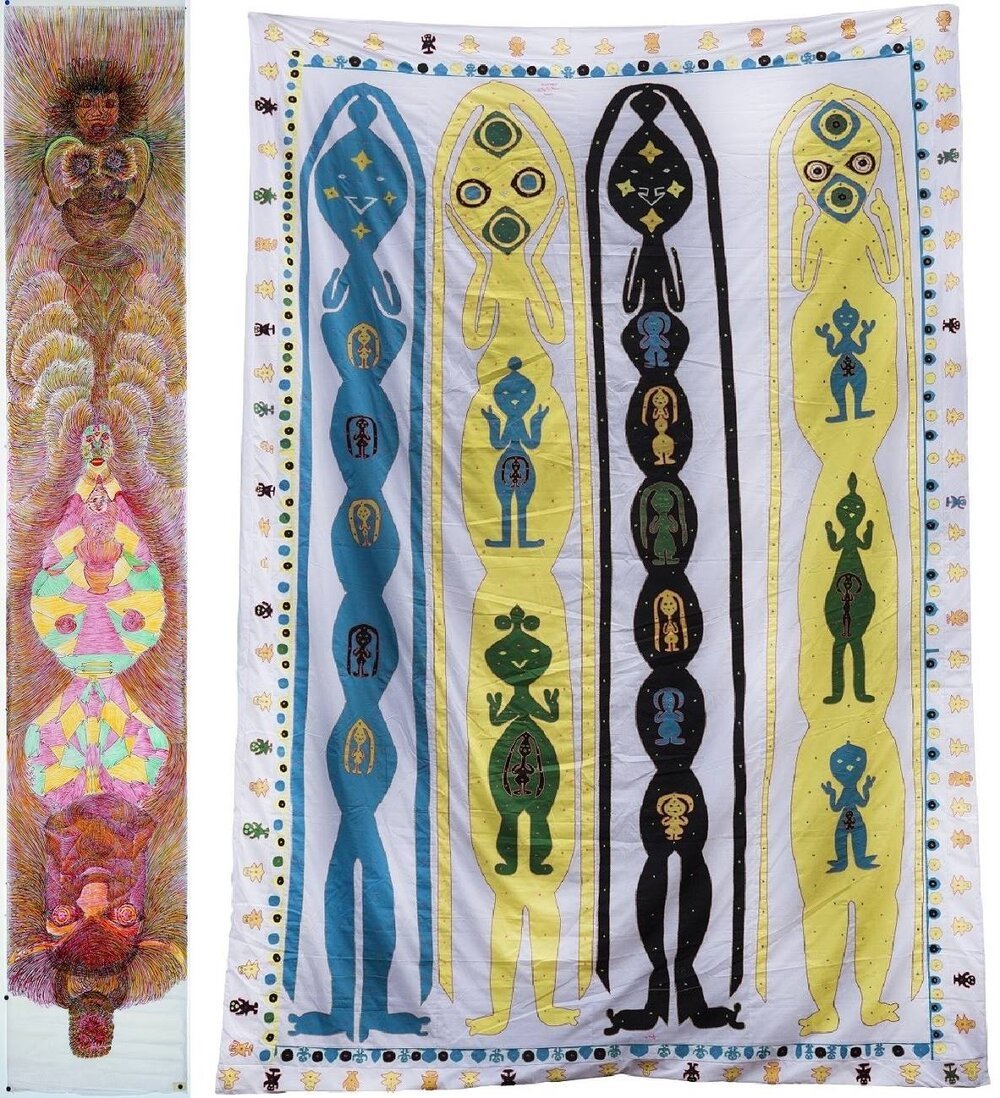

Guo Fengyi, ‘Shaodian (Father of Yellow Emperor)’, 2006, colored ink on ricepaper, 456 × 70cm (left). Tcheu Siong, ‘Three Hmong Protectors 3’, 2018, embroidery and applique on cotton, 423 × 280cm (right). Images courtesy of 2019 Asian Art Biennial.

On that note, I do see how the artworks bring in multiple cosmologies. There were two works that were beautiful in their own right, and at the same time, I felt a conversation going on between them. One is by Chinese artist Guo Fengyi, ‘Shaodian (Father of Yellow Emperor)’, and the other is by Hmong artist Tcheu Siong, ‘Three Hmong Protectors 3’. Conceptually and aesthetically, you can see some similarities, such as the motif of supernatural beings and employing a large-scale hanging presentation. The thing is that they come from two distinctly different worldviews. It’s a lovely visualisation of how multiple worlds can exist together.

Roslisham Ismail (a.k.a ISE), ‘ChronoLOGICal’, 2018, mixed media installation with video, drawing and participatory object, dimensions variable, exhibition installation view. Image courtesy of 2019 Asian Art Biennial.

S: Yes, I liked that aspect too. I also really appreciated the inclusion of the late Roslisham Ismail (ISE). Bringing the Malay world into an East Asian museum is important, and not just from a representational perspective. It is also about acknowledging the similarity across cultures, the connection between East Asia and Southeast Asia. His work is a suggestion of how people move, how things change, and that history is not entirely separated from myth. His work, among others, helps to ground the show. Sometimes, we get too caught up in the post-this, post-that, and we lose sense of what's happening in the now.

SW: After all, when you talk about these other histories, you can't ignore the fact that not very long ago, these areas were interlinked. But because we have been demarcated as Southeast Asia, East Asia et cetera, we operate heavily on this framework. It’s valid, but it’s not helpful to just rely on this structure.

Ting Chaong-Wen, ‘Virgin Land’, 2019, tempered glass floor, ultraviolet light tube, neon lamp, raw material of cinchona tree, tonic water, multi-channel video, dimensions variable, exhibition installation view. Image courtesy of 2019 Asian Art Biennial.

In this regard, I really enjoyed Taiwanese artist Ting Chaong-Wen’s work, an immersive installation titled ‘Virgin Land’. It's in a circular room with five projections lining the walls. There’s also a glass platform in the middle of the room, among other things. As you view the films about the Japanese colonisation of Taiwan and how they exploit the land’s resources, there’s an added sense of precarity and fragility from standing on the glass.

When I was experiencing the work, it felt familiar because it's not so different from when Southeast Asia was colonised. There are converging themes, after all.

S: It was visually stunning, and multi-layered as well, showing how colonialism is linked to environmental issues.

If we just talk about the whole concept of Asian Art Biennial, having a Southeast Asian curator and a Taiwanese curator was an important choice. Whether or not you believe the ‘Out of Taiwan’ theory, you cannot deny the connections between Taiwan and Southeast Asia. There are so many links that we may not see any more due to nationalisation and sinicisation.

SW: The exhibition’s medium size worked as well, because you don’t end up exhausted from trying to absorb too many heavy ideas. Though it also depends on how fast you go, or how much you want to invest yourself in the artworks, particularly the longer video works.

S: I think the sheer number of films and video works can be overwhelming if you stop at every work to watch it in full. Even if you don’t see all the works, there are still many ideas to take away.

SW: I did enjoy how the themes come out strongly for a number of artworks, because biennials are usually done on such a grand scale with so many different works, so it’s a challenge to bring everything together cohesively. As for this Biennial, it attempts to link back as much as possible to its curatorial structure. You also leave the show on a hopeful note: the fact that these works are being presented on a prominent, international platform in such a context is a significant step.

S: There were many good works that communicated important ideas, presented within an intriguing curatorial structure. I definitely enjoyed and appreciated the show in its entirety.

2019 Asian Art Biennial is on show at National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts till 9 February 2020. Read our preview piece here.