The Printed Page: Fine Arts Press and the Publishing of ART and AsiaPacific in Australia (1993-2003)

Australia’s contribution to the idea of “Asian" or “Asia Pacific” art through print

This essay, in tracing the beginning of ART and AsiaPacific now known as ArtAsiaPacific, discusses Australia’s contribution to the idea of “Asian" or “Asia Pacific” art through print. The view that the early essays published in ART and AsiaPacific were formative and remain mandatory reading for students of Asian art do not need further elaboration. I will instead be narrating an as yet little understood coincidence of governance, publishing, and art scholarship for art produced in Asia within Australia at the turn of the 1990s through to the new millennium. At this point, my research does not point to any kind of master strategy for the creation of Asia or Asian art in Australia. Nonetheless, Australians and Australia-based activities had clearly played a significant part in the rise of “contemporary Asian art” as a category.

Australia made concerted efforts to reestablish economic and diplomatic ties with Asia in the 1980s. These efforts extended to art. In 1987, the first edition of Artists Regional Exchange (ARX) brought Southeast Asian artists and art writers to Boorloo/Perth. This biannual artist-led endeavour was informed and supported by Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) funding interests in Southeast Asia. In the same year, Queensland Art Gallery presented ‘Painters and Sculptors: Diversity in Contemporary Australian Art’ in the Museum of Modern Art, Saitama, Japan. Beginning in Tokyo, the newly minted director of Queensland Art Gallery Doug Hall was also searching for a regular collecting exhibition of Asian art for his museum.¹

The Boorloo artists and Hall were looking at Asia, and so were the academics. In March 1991, art historian John Clark organised “Modernism and Post-Modernism in Asian Art”, a conference held in Australian National University, Ngambri/Canberra. The papers were later published by the new Warrane/Sydney-born publisher Wild Peony Press, founded by Mabel Lee, as a book titled Modernity in Asian Art (1993).² Wild Peony focused on Asian scholarship, especially by young Australian scholars. Their purview extended beyond art and they were not deeply connected to the rise of Asian art in Australia. This was accompanied by the efforts of Asialink, based at the University of Melbourne. Asialink Arts, especially through the work of founding director Alison Carroll, directly and indirectly supported the research behind Hall’s exhibitions, which began in 1993 as the Asia Pacific Triennial (APT). APT continues to date, having successfully closed its tenth edition in 2022.

Wild Peony publication in 1993. John Clark (ed.), Modernity in Asian Art. Image courtesy of Wild Peony Press.

Wild Peony publication in 1993. Adrian Buzo and Tony Prince (trans.), Kyunyŏ-jŏn: The Life, Times and Songs of a Tenth Century Korean Monk. Image courtesy of Wild Peony Press.

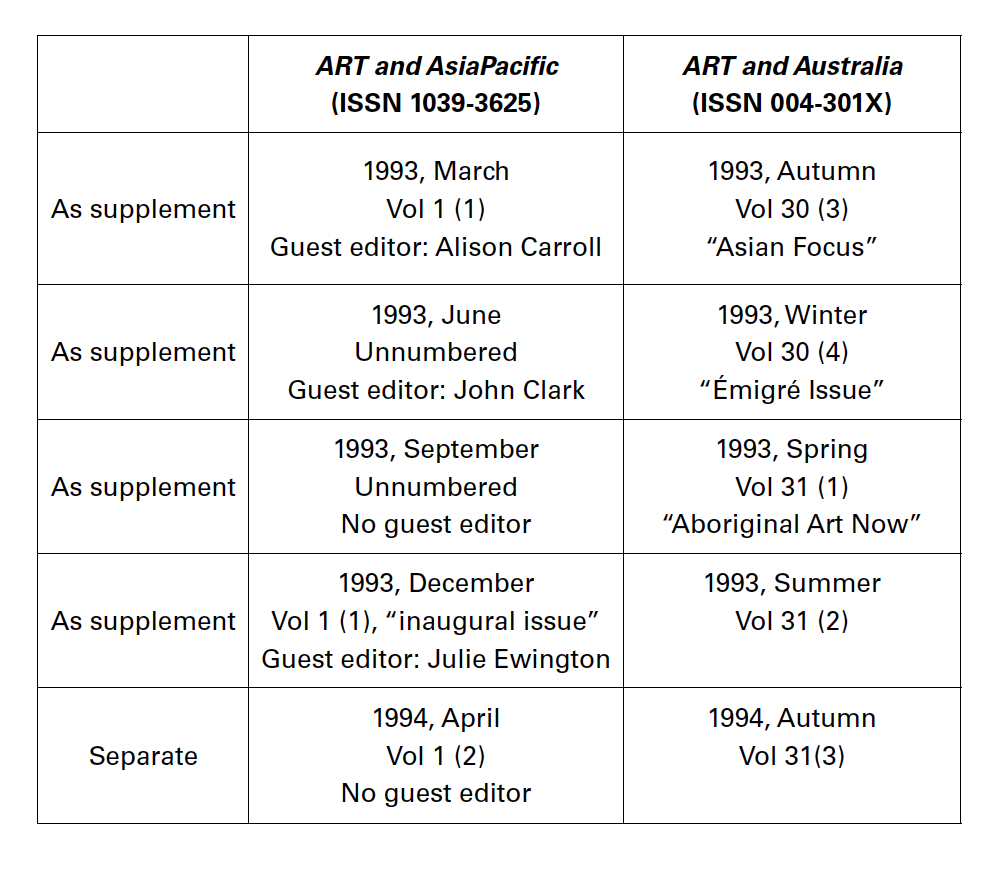

ART and Australia, the preeminent quarterly trade art magazine at that time, was not far behind on these trends. In 1993, they began publishing ART and AsiaPacific magazine, first as a supplement and by November 1993 as a standalone quarterly publication. The dates of the ART and AsiaPacific supplement do not correspond to the dates of ART and Australia. In fact, there were two issues numbered volume 1 issue 1, so the publishing history bears recounting here:

While chronologically aligned, the historical evidence suggests that the birth and rise of ART and AsiaPacific were not related to the changing sentiments of that time. As the magazine’s first editor, Dinah Dysart reminded us when announcing the new magazine in her 1993 editorial, the first 1963 editorial for ART and Australia had pledged to reflect “more of the Pacific, than of European culture. … This magazine will present some aspects of art in countries on our doorstep.”³ ART and Australia has been publishing on Asian art—perhaps, as one may say, before its time. The magazine was already open to supporting and publishing about Asian art and did not need a supplement. ART and Asia Pacific was a different publication made for different intents.

ART and AsiaPacific, Vol 1 No. 1 (Mar 1993), guest edited by Alison Carroll. Cover from Vasan Sitthiket, ‘Sinners are gunmen who serve the mafia and tyranny, oppressing peaceful men to be afraid, doing unlawful business, making trouble everywhere. They will be surrounded by flocks of hungry dogs and crows gatheringly eat them, they will die and be reborn again and again for five hundred kalpas’, 1991, acrylic on canvas, 210 x 210cm, collection of Peera Ditbunjong, Bangkok. Reproduced with permission from Vasan Sitthiket.

ART and Asia Pacific, Vol 1 No. 1 (Dec 1993), guest edited by Julie Ewington. Cover artwork by Junyee (Luis Yee Jr), ‘Gomi Tower from City Things’ series, 1991, nylon fishnet, hi-fi speaker, refrigerator, exhibited in Fukuoka, Japan. Photo by Kazumasa Satoh.

ART and Australia was first published as Art in Australia between 1916 and 1942 by Sydney Ure Smith (b. 9 January 1887, Stoke Newington, London – d. 11 October 1949, Warrane/Sydney). His son Sam Ure-Smith (b. 1922, Warrane – d. 2013, Warrane) began printing ART and Australia after the war, in 1963, and it has not stopped since. It was an emotional legacy for Ure-Smith junior, and he felt an obligation to ensure its continuity.

After almost 80 years of publishing Art in Australia/ART and Australia/art&australia, the Ure-Smiths were exiting the publishing market. Sam Ure-Smith was getting old; he recalled in his interview with the National Library of Australia that he would be 70 years old in 1992. However, his daughters Susan and Ann were not interested in the business.⁴ He found his successor in American publisher Martin Gordon (b. 1933 – d. 19 February 2015, Lausanne, Switzerland), founder of Gordon and Breach (G&B). In 1991, G&B would buy over Ure-Smith’s company, Fine Arts Press, marking the beginning of new leadership for art publishing in Australia.

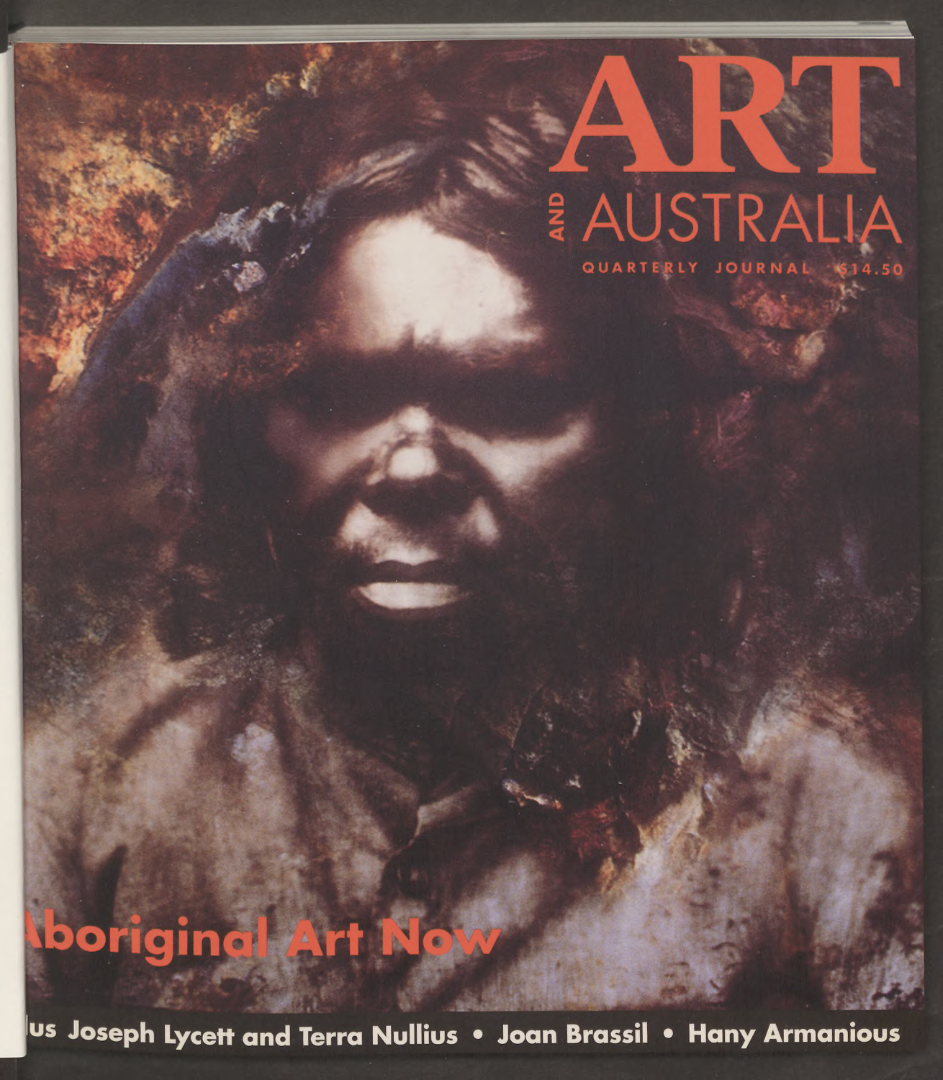

ART and Australia, Vol. 31 No. 2 (Summer 1993), “Aboriginal Art Now”. © 2024 by ART and Australia CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

ART and Australia, Vol. 30 No. 3 (Autumn 1993), “Asian Focus”. © 2024 by ART and Australia CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

G&B went on a buying spree in Australia. Other than Fine Arts Press, Gordon also bought over Craftsman House, established in 1981 by Geoffrey King. Craftsman House was the finest art book publisher in Australia. At that time, he also acquired 21C: The Magazine of Culture, Technology And Science, an international art magazine with a strong interest in new media established in 1990 by the Commission for the Future. From ART and Australia, Gordon began ART and AsiaPacific. From 21C, World Art: The Magazine of Contemporary Visual Arts was conceived. ART and Australia and ART and AsiaPacific shared an office in Warrane, while 21C and World Art was edited from Naarm/Melbourne. Each magazine had their own editorial staff, even if they were housed in the same offices. From the same Warrane office, Hari Ho (b. 1948, Ipoh, Malaysia) oversaw production of all four magazines as well as books by Craftsman House. What this meant was that through the 1990s until G&B’s Australian operations were broken up and sold by Rhonda Fitzsimmons between 1999 to 2003, any writing of note about art from anywhere being published in Australia would have passed through Ho’s desk.

While it is hard to remember in our contemporary present, where digital photography and digital publishing are dominant, physical art books and magazines used to be the only way art could be seen and circulated outside the gallery. Improvements in print were akin to an upgrade to the screen resolution in our devices: everything became much more appealing, accessible and digestible. While there was a critical mass of scholars looking at Asian art in Australia and elsewhere in this period, and high-quality criticism was being published in ART and AsiaPacific, the appeal of this publication was also its practical materiality. Dysart was explicit in her editorial.

We are very proud of ART and AsiaPacific. Modelled on ART and Australia it presents informed criticism and comment on contemporary art supported by high quality reproductions. The emphasis is on visual impact and expert opinion from writers of each region. [My emphasis]

Dinah Dysart, Editorial for ART and Australia, 31:2, (1993).

“High quality reproductions” and “visual impact” distinguished G&B publications from others that may be working with the same writers. They were simply printing better books. Through the consolidation of fine art publishing by G&B in Warrane, including the birth of ART and AsiaPacific, printing standards were being elevated. Lesser understood “Asian” art was seen in Australia and, through G&B’s global distribution network, internationally in a way that was not possible before. Again, art from Asia was already being seen and knowledge was being created about this art from ART and Australia and other publications from Australia, Japan, and elsewhere. What accelerated visibility and definition of “Asian” art in this period was better print. This would not have happened without firm and consistent leadership both from Gordon and Ho.

Ho had joined Fine Arts Press as Production Manager in 1991. He was hired by Ure-Smith a few months before the G&B deal was sealed, but stayed on to work with Gordon, throughout G&B’s entire presence in Australia. In G&B, Ho managed a studio of designers: one each for quarterlies Art and Australia, Art and AsiaPacific, World Art and 21C, one for Craftsman House imprints and other freelancers as appropriate.

At its peak, Craftsman House was publishing 40 books a year. While each magazine and Craftsman House had their own editorial committee and design philosophy, Ho provided overall quality and aesthetic oversight, maintaining an exceptionally high standard. Naturally, improvements in print for one publication would carry over to the next and Ho's design studio was one of the best places for the print craft in that decade. Gordon bankrolled the entire operation at a loss through G&B with minimal intervention. With his support, these magazines and the Craftsman House books became well-regarded books of this decade.

I emphasise the unprecedented physical and material support for art publishing in Australia in the late twentieth century and its impact on the art discussed within the pages. The object nature of these magazines and books, which has largely fallen out of favour internationally, has been crucial in distributing and creating “Asian” art, and the reputation of ART and AsiaPacific, in a world before the internet. Without forgetting the intellectual rigour in the pages, much more remains to be said and researched about the literal pages: the type of paper, quality of ink, colour matching standards, and other “lesser” material concerns.

The author is currently employed as Digital Archive Researcher with Art+Australia. All opinions are her own but facts are cross checked with current and some past Art and Australia staff and contributors. This essay has been proofread by current Art+Australia staff prior to publication.

This article is a part of CHECK-IN 2024, our annual publication, which comes in at 313 pages this year. You can buy a limited-edition print copy at SGD38 here.