Nổ Cái Bùm in Huế and Đà Lạt

Art as Non-Structural Mitigation in Central Vietnam

Melissa Reed wrote that “non-structural mitigation in emergency management involves what people can do on a personal level that is not structurally or physically evident as a protective defense such as a surge wall or a storm shelter”.¹ Taking cultural and political obstacles in Vietnam as natural disasters, the use of Vietnamese contemporary art to deal with particular circumstances could be seen as managing emergencies. To understand the strategies used, this article examines the operation of Nổ Cái Bùm (NCB), an annual contemporary art week in Central Vietnam.

Lê Lan Anh, Âm, 2019, video still. Image courtesy of the artist.

Non-Structural Structure

NCB’s organising structure is a non-structural mitigation enabling the art week to deal with any ‘disaster’ that might occur based on personal connections among Vietnamese art practitioners. Brainstormed and organised within three months firstly in Huế, NCB literally means a ‘boom’, or an explosion characterised by its suddenness. As curator Lê Thiên Bảo imagined, NCB’s structure was like a “rolling ball” that contained creative ideas in itself. Given that Central Vietnam is quieter in the contemporary art scene than Hanoi and Saigon, the art week was born from common interests in making art in the art spaces Mơ Đơ, Nest Studio and Symbioses.

Hoàng Anh, Vô Đề (Untitled), 2020, mixed media. Image courtesy of the artist.

Mơ Đơ is a loose artist collective founded as a wine bar in a junky garden in the formal imperial citadel by Huế-based artists Trương Thiện, Hoàng Ngọc Tú and Nguyễn Thị Thanh Mai, and Phương Linh from Hanoi. The artist bar opened for film screenings and art events besides selling drinks. Nearby, Nest Studio is a combination of artist studios and room rentals founded by artists Đào Tùng and Ngô Đình Bảo Châu in 2019. Besides its resident capacity, Nest Studio also includes artist gatherings, talks, film screenings and art events. Likewise, Symbioses is an art project initiated by curator Lê Thiên Bảo. Interested in the relation between arts and business, Thiên Bảo wants to create a connection between the art world and local enterprises. Via Symbioses, she aims to bring art to casual spaces and to change people’s habits towards appreciating and collecting artworks.

Standing on this structure, NCB in Huế was made up of artworks, performances and presentations of 56 artists between 4 and 9 July 2020. Without any curatorial frame, participating artists tailored their own shows with each other. This organisational structure might have lacked professionalism but artist Đào Tùng noted that it offered an expansive space for liberal minds. In spite of lacking a legal body, the art week received material and and other types of contribution from a number of artists and private donors in the whole country including the Japan Foundation², which enabled it to move forward.

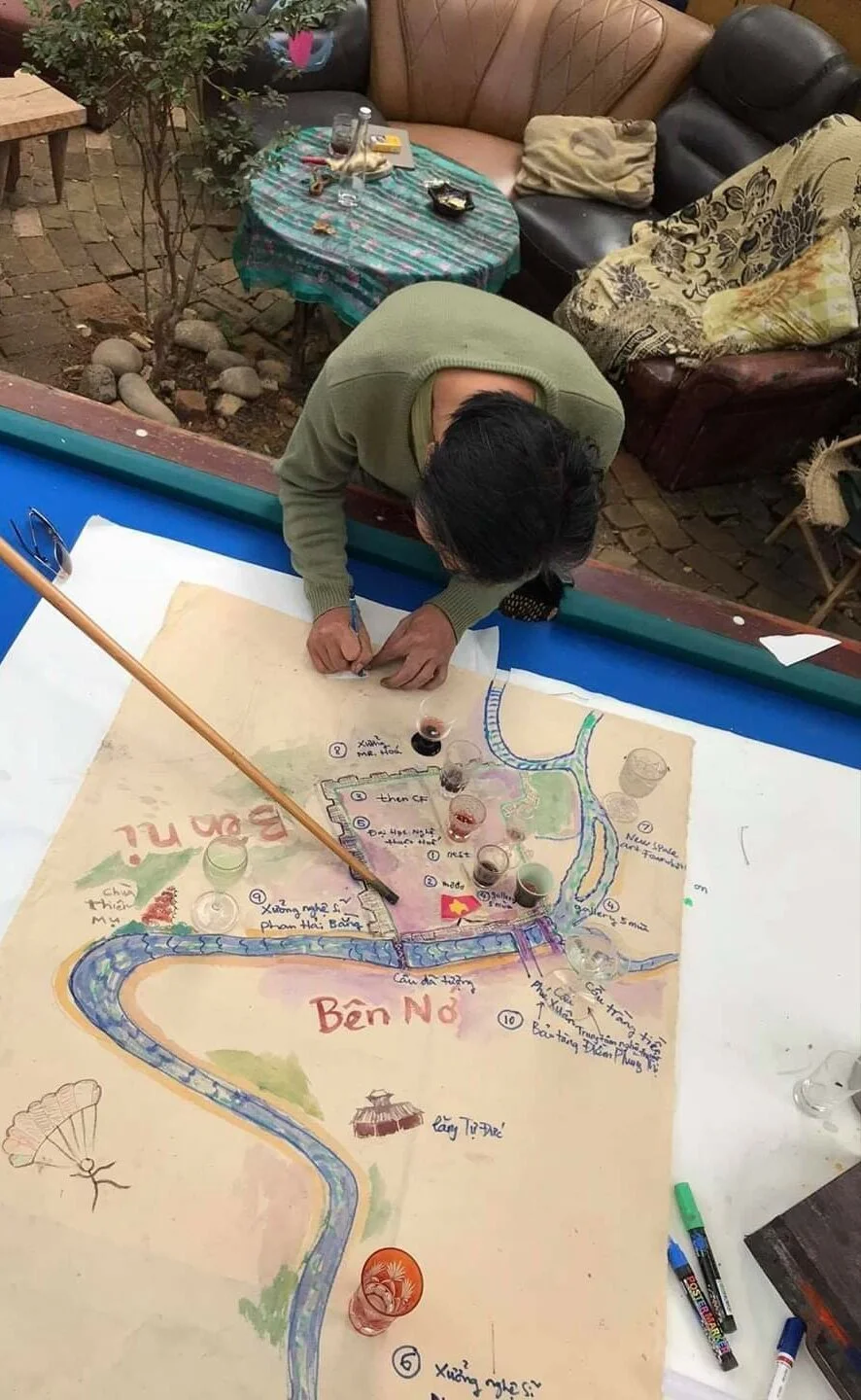

Artist Nguyễn Đức Đạt drawing the NBC (2020) event map. Image courtesy of NCB (2020).

Rolling in The Spaces

Under these conditions, the art week rolled into all possible corners to transform them into art. Artist Nguyễn Văn Hè’s Mazda 1200 from 1966 of artist was used for the performance piece ‘Trước giờ khai mạc’ (Before Opening) by Hoàng Ngọc Tú. In the form of a loudspeaker installed in a car, the pre-opening turned the old car into a mobile art space cruising around the touristic citadel to boisterously announce NCB 2020³. Using exactly the same propaganda instrument as the government, the satirical performance made it past the censoring gaze throughout the programme.

Regarding the serious watch of Huê’s cultural officials, NCB navigated itself flexibly through difficulties. The authorities’ seriousness could be seen in their careful scan of artworks’ contents and their attendance at all art events. During the artist talk by Nguyễn Trinh Thi, cultural security forces rushed in because of an extra screening. Without permission, the authorities threatened the artists to charge 40 million Đồng (or about USD1.735) as penalty and demanded to destroy the movie. The idea of the movie’s destruction could only be assumed as the authorities’ permanent belief in analogue films before the digital era.

Lêna Bùi, Sơ đồ cá nhân #1 (Personal Map), 2020, ink and watercolor on paper. Image courtesy of the artist.

To make sure none of the unallowed artworks was able to slip through their fingers, the authorities carefully scanned around 44 videos, artist talks and performances. Amongst those, 14 artworks were prohibited, one of which was a video artwork by Lan Anh, who had passed away shortly before. The reason for censoring the artwork was its twelve-hour length that challenged the authorities’ patience. The prohibition was announced just a few days before the opening, leading to a rushed rearrangement of the artworks.

Facing this situation, six planned exhibition spaces of NCB were reduced to five. Nest Studio was then excluded and turned into X-space – a hidden place showcasing all censored artworks. Corrections on printed matter and social media were quickly done. Yet, news on the hidden exhibition were spread among friends and the number of visitors was incredibly crowded. Artist Đào Tùng, also the founder of Nest Studio, stood in front of the studio to watch out for the authorities.⁴

Still, NCB’s art spaces were not offered from any local enterprise as the hope had been, except from Huế-based artists and Hue University – College of Arts. The connection with the college came from artists Trương Thiện and Nguyễn Thanh Mai, both lecturers there. According to the artists, the college was relatively open to external cooperation, for it was at risk of becoming redundant with limited funding and enrollment.⁵ Relying on these alternatives, the NCB kept rolling the ball on its own lines of non-structural mitigation.

Nguyễn Đức Đạt & Laurent Serpe, Nghệ thuật Vạn Tuế! (Art Forever!), 2020, before burning view. Image courtesy of Yatender.

Nguyễn Đức Đạt & Laurent Serpe, Nghệ thuật Vạn Tuế! (Art Forever!), 2020, before burning view. Image courtesy of Yatender.

Dancing in Line

This non-structural mitigation, indeed, helped the art week get through not only the censorship, but also some particular obstacles caused by the city’s character. Like dancing in a line, NCB executed the steps rhythmically with any hindrance appearing. Being part of the vanished Republic of Vietnam, Huế contains in itself thick layers of hidden history including the cruel battle in 1968 known as Mậu Thân Massacre or Tết Offensive that resulted in thousands of unjust deaths.⁶ Preserving many traditions related to those kinds of incidents, a fear of another world and a belief in wandering vengeful spirits is entrenched in the local culture.⁷

In NCB 2020, the fear appeared in facing the installation Nghệ Thuật Vạn Tuế! (Art Forever!) by artists Nguyễn Đức Đạt and Laurent Serpe. The object installation performance was inspired from the widely seen worshipping and votive offerings in town. Coming from this area, the artists found these customs touching. Besides, the market for the dead offered everything except art supplies. Within two weeks, an artist studio was built from colour paper, papier-mâché and cardboard. The craftsmanship was not made by casual craftsmen because of high-cost restrictions, but rather for want of a lesser quality. The artists specified that the votive offerings must be real as it would be truly needed in another world. Thinking in English, the work Art Forever! is a tease on what comes next after Art Now – a trendy name for books on contemporary art. Likewise in Vietnamese, ‘Nghệ Thuật Vạn Tuế’ is a play on common political slogans in the country. All of these offerings and objects were set up for a week and burnt on the ground of Hue College of Arts on the final day of the art week. Before burning them, the artist and friends brought in fruits, flowers and burnt the incense for worshipping. Đạt was sentimental as he reflected on other deceased artist friends and his own mortality as the objects vanished in the fire. The artist shared that “it was fun to do something invaluable and nonsensical” when speaking about the non-commercial artwork.⁸

Quốc Thành, Phan Đông Thái, Tăng Xông (Sauna/Tension), 2020, performance. Image courtesy of the artist.

However, the rituality of the artwork scared some Huế’s artists. Coming up with the idea of making all censored artworks as votive offerings and burning them at the opening, Đào Tùng’s suggestion was rejected because of the “bad luck” it might cause. Huế is believed to be a very sacred city,⁹ and is also a city under strict watch. In the end, a votive television was still realised and carried around NCB’s art spaces by Đào Tùng to commemorate the censored art works.

Nevertheless, the fear of ghosts belonged not only to the folks but also the authorities. After crashing the artist talk of Nguyễn Trinh Thi, Huế’s authorities asked NCB’s organizers whether the name of the art week was related to the battle Mậu Thân in Huế. Although the massacre is unwritten in the country, its vivid stories are engraved in the collective memory, including the authorities’. The curator said the historical event was uninvolved for she was but a young girl when it happened and that she simply meant for it to mean a jolly explosion of art. This answer helped her to leave the casual interrogation unscathed. At the same time, the scale of the art week resulted in a warning issued for raising funds abroad by the Saigon police before her departure to France for study.

Scenario at Mơ Đơ. Image courtesy of Nguyễn Anh Tuấn.

The Rolling Ball

Overall, the concept of NCB is not fixed to any permanent form or space but mobilised in different cities. Like a ball that could be kicked off by anyone and able to roll in many different spaces, this year, NCB rolls to Đà Lạt. In a collaborative effort among art spaces Saola – Cù Rú, Mơ Đơ, Nest Studio and Symbioses, NCB will bloom in the Vietnamese central highland city, where a certain number of characters and histories also remain. Dreaming (mộng mơ) is the inspiration for NCB 2021 from Đà Lạt’s character. Depending on upcoming situations including the COVID-19 pandemic, the organisers for this edition of the NCB plans draw its own specific lines, working with over 100 artists between 8 and 15 May 2021.¹⁰ What it will bring to life is waiting for us all ahead!

Notes:

Melissa Reed 2015. “Mitigation: Structural and Non-structural.” PennState Public Health Preparedness: Building Disaster Resilient Communities with M. Reed, May 05.2015. https://sites.psu.edu/workworthdoing/2015/05/06/mitigation-structural-and-non-structural/#:~:text=Non-structural%20mitigation%20in%20emergency,such%20as%20having%20flood%20insurance [Last accessed on March 26,2021]

https://www.facebook.com/103337114583032/posts/160168282233248/ [Last accessed on March 26,2021]

https://www.facebook.com/nocaibum.hue/videos/1209670572751643 [Last accessed on March 26, 2021] and from my chat with Đào Tùng via Facebook Messenger on February 5, 2021.

From my interview with Lê Thiên Bảo via Zoom meeting on January 26, 2021 and chat with Đào Tùng via Facebook Messenger on February 5, 2021.

Cát Tường 2018. “Đại học Nghệ thuật đang chết lâm sàng trên đất Huế.” Lao Động, 31.03.2018. https://laodong.vn/xa-hoi/dai-hoc-nghe-thuat-dang-chet-lam-sang-tren-dat-hue-598671.ldo[Last accessed on March 26, 2021].; Đại Dương 2019. “Hàng chục giảng viên, cán bộ trường ĐH Nghệ thuật, ĐH Huế bị chấm dứt hợp đồng.” Dân Trí,16.10.2019. https://dantri.com.vn/giao-duc-huong-nghiep/hang-chuc-giang-vien-can-bo-truong-dh-nghe-thuat-dh-hue-bi-cham-dut-hop-dong-20191016112220290.htm [Last accessed on March 26, 2021]

Nguyễn Quý Đức 2018. “Revisiting Vietnam 50 Years After the Tet Offensive.” Smithsonian Magazine, Janary/Feburary 2018. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/revisiting-vietnam-50-years-after-tet-offensive-180967501/ [Last accessed on March 26, 2021]; Nhã Ca 1969. Giải khăn sô cho Huế. https://www.vinadia.org/giai-khan-so-cho-hue-nha-ca/ [Last accessed on March 26, 2021]; Liên Hằng T.Nguyễn 2012. Hanoi’s War: An International History of the War for Peace in Vietnam. UNC Press 2012.

Bảo Ninh 1990. Nỗi buồn chiến tranh (The Sorrow of War). Nhà xuất bản Trẻ 2011. Heonik Kwon 2008. Ghosts of War in Vietnam. Cambridge University Press 2008.

From my interview with Nguyễn Đức Đạt via Facebook Messenger on January 27, 2021.

From my interview with Lê Thiên Bảo via Zoom meeting on January 26, 2021

https://www.facebook.com/nocaibum.hue/photos/a.103354111247999/268923324691076/ [Last accessed on March 30,2021]