NFTs: The Good, The Bad, The Uncertain Future

Southeast Asian artists experiment with digital artworks

Jonathan Liu, Turbulence (Super 8), 2017, shot on Super 8 film, digitally processed. Image courtesy of the artist.

Singapore artist Farizwan Fajari, better known as Speak Cryptic, minted his first Non-Fungible Token (NFT) artwork on March 14, 2021. The visual artist, working across drawings, installations, public art and performance-based mediums, was first introduced to the digital asset earlier this year, prompted by the media frenzy surrounding Christie’s auction of Beeple’s Everydays – The First 5000 Days. Beeple’s collection was the first instance of an art auction house offering a fully digital artwork and as an NFT. The work went on to achieve a jaw-dropping price of USD69.3 million, prompting many to ask: what is an NFT, and what does it mean for the future of art?

An NFT is a unique digital asset stored on the blockchain that can refer to digital artworks and collectibles. Blockchain is a digital ledger of data that is distributed across a decentralised network of computer systems. The technology facilitates a record of transactions that is immutable, transparent and entirely traceable. One of its key applications is cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin and Ether. Bitcoin is a fungible asset, as different units of Bitcoin are mutually interchangeable. An NFT, in contrast, is by definition a unique asset. It cannot be equally swapped or exchanged for another. Each NFT is authenticated by blockchain, encoding within it a smart contract, or a string of code and metadata that certifies its ownership and provides information about the asset. NFTs generate and maintain digital scarcity, a feat that was previously less accessible within a digital economy of infinite reproducibility and shareability.

NFTs first entered mainstream consciousness in 2017, with the rise of projects such as CryptoKitties, a collectible-centred game developed by Dapper Labs. But it was only this year, driven by the heightened interests in cryptocurrencies and astronomical prices fetched by works by artists like Beeple, that we observe a widespread, rapid adoption of NFTs by artists across the world.

In Southeast Asia, a growing number of artists are beginning to move into the NFT space to explore new possibilities brought forth by the platform. Singapore-based Jonathan Liu, an image-based practitioner, first became interested in learning about NFTs as he was looking for ways to sell intangible and digital artwork. NFTs are able to refer to digital images, 3D renderings, , sound clips, graphic illustrations, and more, offering artists the potential of selling immaterial artworks that are less conventionally offered in the traditional art market. Malaysian multidisciplinary artist, Chong Yan Chuah, embedded an NFT in the online presentation of his collaborative exhibition, FAC3D, exploring the complex relationships between the human identity and the virtual realm. Chong’s NFT is a video of five 3D-rendered human figures stacked on top of each other, suspended in air, playing on loop. Fashion photographer, Shavonne Wong from Singapore, offers NFTs on animations of her 3D virtual models, an extension of her virtual modelling agency, Gen V. Antonius Oki Wiriadjaja, an Indonesian-American performance and new media artist, sold a 15-second 720p video as his first NFT.

Chong Yan Chuah, ISO_D_ 01, 2021, 30-second video on loop. Image courtesy of the artist.

Artists are also interested in how NFTs may grant them greater artistic autonomy, direct sales channels and copyright protection. Khai Hori, Director and Partner, Chan + Hori Contemporary, Singapore, observes that many artists who have turned to NFTs have a “strong desire to break free from traditional and domineering structures” of the art ecosystem. Chan + Hori Contemporary represents artists such as SpeakCryptic, and encourages them to pursue their interests in venturing into the NFT space independently, while continuing to advise them on longer-term trajectories. NFT marketplaces allow artists to list their artworks directly, bypassing the gallery system that traditionally took large cuts for selling and promoting an artist’s work, as Singaporean photographer, Ernest Wu, shares. Wu, Liu and Wong also note that NFTs allow artists to indicate resale royalties in the smart contract, which will be credited directly to the token creator’s digital wallet as soon as the work is resold. This ensures that artists will be compensated for their works in secondary sales, a fee that is typically tricky for artists to secure in the wider art market.

Indeed, artists are often plagued with concerns of copyright when uploading or screening their works online. After an image or digital file is uploaded onto the web, it is difficult to track and control who is able to view it, download it, reuse it, and for what purposes. With NFTs, however, Wiriadjaja shares that the token is able to authenticate the original creator of the token, allowing the artist to be credited as the asset’s originator, regardless of how the attributed file may be shared.

Antonius Oki Wiriadjaja, Cheese Board Mask, 2020, 15-second video. Image courtesy of the artist.

Paradoxically, rampant art theft has infiltrated NFT marketplaces, as some have claimed ownership and sold NFTs of artworks that are not their own. Indonesian illustrator Kendra Ahimsa, or Ardneks, announced on his Instagram that his artworks had been plagiarised by NFT collective, Twisted Vacancy. While Twisted Vacancy has admitted to drawing heavily from elements of Ardnek’s illustrations and images, the NFTs that Twisted Vacancy has created and stored onto a blockchain cannot be modified or deleted, a characteristic of blockchain technology. Presently, there are not yet established protocols or regulations that ensure the seller of an NFT is the original creator of the attached artwork. However, many have pointed out that art theft has long existed within the art market and is not a problem unique to NFTs.

Another key issue associated with the rise of NFTs is the high energy usage of blockchain, cryptocurrencies and relevant applications. The majority of NFTs today are minted on Ethereum through a mechanism called Proof of Work, which involves a network of specialised computers with high computational powers to validate transactions. While alternative, less energy-intensive mechanisms such as Proof of Stake have been adopted by other blockchains, and Ethereum in the process of moving towards more sustainable processes itself, it remains that NFTs may impose significant energy costs to be created and maintained. In response, artists like Wiriadjaja believe that the community must dedicate research and serious thought into improving the underlying technologies behind NFTs, to develop the platform and improve its sustainability overtime.

Behind the exciting opportunities offered by NFTs, there also lies a dark side to digital asset’s unregulated marketplaces. Andrew Bailey, Associate Professor at Yale-NUS College, and co-author of an upcoming publication on Bitcoin, points out that foul play may have been involved in high level trades of NFTs, which can be traced by following the on-chain transaction data. Dr. Jin Li Lim, Co-Founder of QCP Capital in Singapore, further warns of growing concerns surrounding the use of NFTs for money laundering and illicit activities.

“Artists entering the NFT space are commonly in agreement of the digital asset’s early maturity, especially in comparison to mechanisms within established art markets, and accept the risks and volatilities attached to trading in cryptocurrencies.”

The speculation and hype have led skeptics to question if NFTs merely present another financial bubble that will soon burst. Artists entering the NFT space are commonly in agreement of the digital asset’s early maturity, especially in comparison to mechanisms within established art markets, and accept the risks and volatilities attached to trading in cryptocurrencies. Hori proposes that “artists, collectors, curators and galleries wanting to engage must be willing to do so beyond their existing comfort and power zones.” In this relatively nascent addition to the larger arts ecosystem, artists must learn to navigate and respond to a new set of rules, which presents opportunities alongside its challenges.

Looking into the future, both Bailey and Lim are optimistic about the growing interests, developments and adoption of cryptocurrency and blockchain innovations across Southeast Asia. Commercial galleries such as Mucciaccia Gallery, which has a physical space in Gillman Barracks in Singapore, have begun to accept Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies as payments for their sales. The increased adoption of cryptocurrencies may drive further demand for NFTs within the region, making it more attractive for artists to use the platform as an additional distribution channel for their artworks. At the same time, the increased demand for cryptocurrencies and NFTs will also lead to an increase in gas fees, the amount required to create an NFT on the blockchain. At the time of writing, creating an NFT on Ethereum can cost anywhere between USD100 to USD200, a fee that poses a high barrier of entry to many, especially in countries with weaker currencies.

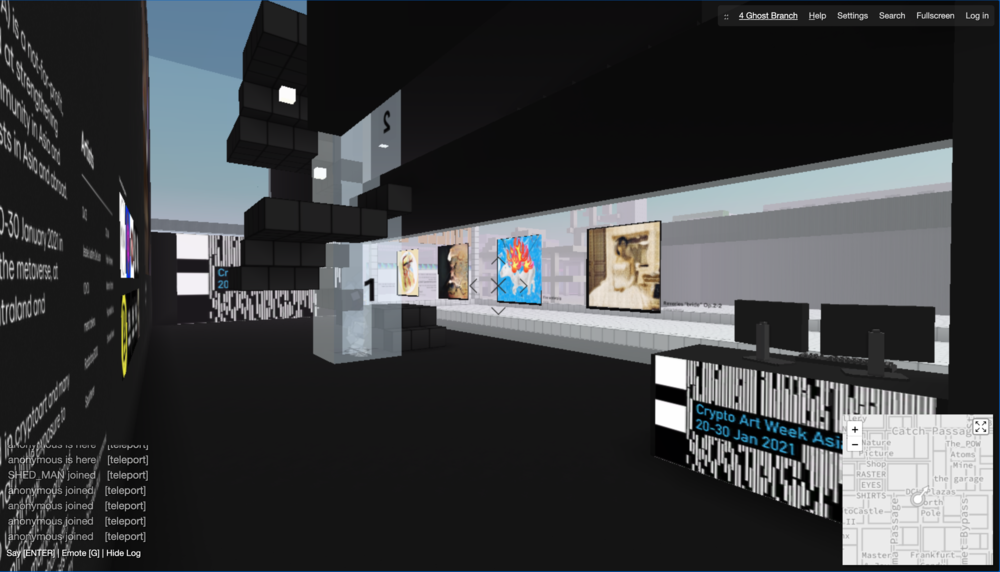

In an effort to make NFTs more accessible to newcomers, the First Mint Fund, managed by Philippine-based AJ Dimarucot, is offering to sponsor artists the fees required to create their first NFTs. Colin Goltra and Gabby Dizon, also based in the Philippines, launched Narra Gallery, an open gallery space in Decentraland, to showcase crypto art and NFT projects. Decentraland is a virtual reality platform powered by Ethereum, where users can buy, develop and sell virtual land. Earlier this year, Crypto Art Week Asia also ran in tandem to Singapore Art Week in late January, with both a digital presence on Decentraland and Cryptovoxels, a similar virtual world, and a physical presence at Kult Yards in Singapore, to reach a diversified audience.

Crypto Art Week Asia.

Globally, many believe that NFTs will play an increasingly important role in visual cultures and art histories in the years to come. While the future remains uncertain, Wiriadjaja shares that it is important to claim one’s space within this rapidly moving scene, and be a part of shaping the conversation. Speak Cryptic also pointed out that, as with any artistic form, those entering this space should respect the medium and format that NFTs offer, and strive to create works that sincerely serve and respond to the platform. Regardless of whether one is a firm believer or a fierce critic of NFTs, the digital phenomenon has shaken up the global—and regional—art world and opened our eyes to the powers and potentials of art in the age of blockchain, and many of us like what we see.

This essay was first published in CHECK-IN, A&M’s first annual publication. Click here to read the digital copy in full, or to purchase a copy of the limited print edition.