Review of ‘The Curious Adventure of Madame Điềm’s Modules’

Điềm Phùng Thị's sculptures at The Outpost Art Organisation, Hanoi

By Vy Dan Tran

Almost 30 years have passed since Điềm Phùng Thị’s last exhibition at 32 Bà Triệu Street in Hanoi in 1995. However, that exhibition is little known, especially to a contemporary audience, for whom Điềm Phùng Thị remains quite a mystery. This is despite the artist’s reputation in the second half of the 20th century in Europe, where she lived and worked. On 22 September 2024, The Outpost Art Organisation opened a show titled ‘The Curious Adventure of Modules’ to introduce Điềm Phùng Thị’s sculptures alongside video installations by Hachul Lệ Đổ, Ngô Đình Bảo Châu, Đỗ Thanh Lãng, Hải Duy and Lê Thuận Uyên. Accompanying the artworks were documents, catalogues and photographs about Điềm Phùng Thị from Vietnam and Singapore collected by artists and curators. According to the organisers, ‘The Modules’ is “a research-focused exhibition dedicated to exploring the evolution of the late artist Điềm Phùng Thị’s unique sculptural language”; but as the show unfolds, the main research subject is ambiguous. For the general audience, this “visual essay” is not coherent, and for the aficionado, it lacks substance, resulting in an unsatisfying experience for both.

One would hear about the Vietnamese modern sculptor Điềm Phùng Thị (1920–2002), whose maiden name was Phùng Thị Cúc if they visited Lê Lợi Street in Hue. Prominently situated on that street is Điềm Phùng Thị Art Foundation, a colonial villa housing 367 artworks by Điềm Phùng Thị, who was also called Madame Điềm.¹ Madame Điềm was born and passed away in Hue, but her most fruitful years happened in France, where she obtained a PhD in Dental Surgery in 1954. She branched out into sculpture in her early 40s, beginning her artistic career at the atelier of Antoniucci Volti (1915–1989). In 1991, Madame Điềm was honoured in the Larousse Dictionary: “Art of the 20th Century”. Her works were showcased in France, Italy, Denmark, Germany, and Switzerland several times before the artist returned to Vietnam in 1992. Since then, Điềm Phùng Thị donated many works to the city Hue and she is very well-known among local artists.

‘The Curious Adventure of Madame Điềm’s Modules’, 2024, installation view at The Outpost, Hanoi. Photo by Vy Dan Tran.

The current exhibition dedicated to Madame Điềm at The Outpost centres around modules, her signature sculptural modus operandi. The critic Đặng Tiến compared her ultimate set of concise seven modules, or signs, to lines in Han characters.² The modules are arranged to assemble variable forms, creating a dominant visual style. The 17 sculptures on display were produced between 1960 and 1994, and are either small or medium-sized, primarily made of bronze, wood, jewel, stone and lacquer. Yet, Madame Điềm’s modules found its ways into broader configurations including public monuments, jewellery, fabric, and so on. For audiences who are familiar with Madame Điềm’s works, it may seem that her most engrossing and impressive pieces are not present at the exhibition. For instance, the enlarged elaborate modular sculptures that are shown in the printed scans of historical catalogues. ‘The Modules’ is rather underwhelming due to the modest scales of both the space and the artworks. Not to mention that three or four sculptures on view are not archetypally modular, and one might ask what their relations to the modular ones are. The restricted choice of artworks insufficiently represents the versatile potential of the distinctive modular vocabulary.

Điềm Phùng Thị, ‘Praying’, green onyx, black marble, 38 x 30 x 30cm. Photo by Vy Dan Tran.

Some of the miniature sculptures displayed on the black table. In front is Điềm Phùng Thị, ‘Untitled’, lacquer, bronze, 5.7 x 2.1 x 4cm. Photo by Vy Dan Tran.

Although ‘The Modules’ belies the inherent verve and profundity of Madame Điềm’s creations due to its paucity of original artworks, it offers a fun and intimate perspective. While the sculptures on display tend to depict human figures semi-abstractly, such as ‘Father and Son’ (1994), one work stands out with its abstract-looking polish and medium size. Sleekly patterned, ‘Praying’ (1978), made of green onyx, is the most aesthetically pleasing work in the show. Nearby are ten miniature sculptures on a black table in a dark room. The modular ones are reminiscent of the tangram with its simplicity, open-endedness and timeless quality. Madame Điềm’s oeuvre is a structural amalgam of organic and geometric shapes, symbolising a universal language of love and compassion.

Without a clear direction guide, the exhibition is presented across four small areas and it is up to the viewer to decide if they wish to begin with contemporary video art, historical photographs or Madame Điềm’s sculptures. This open format can lead to a sense of disorientation. One of the first things the viewers will encounter as they enter the exhibition is an animated video installation by a contemporary artist, the first of the three episodes, envisaging the evolution of Madame Điềm’s modules. However, since the videos do not have a narrative, they do not offer insight on how Madame Điềm’s work have progressed over time. Moreover, there is a dissonance between the mood of the video and Madame Điềm’s sculpture. While the latter exude solemn and tranquil vibes, the animation seems to be jovial and playful. The animation helps bring the modules to life, but at times, it can be distracting with its fairly loud experimental sounds. The videos should be placed at the end of the exhibition, after the visitors have already gained an understanding of Điềm Phùng Thị and her modules. Alternatively, a documentary about the making of the modules might be more engaging and enlightening.

The replica of the set of seven modules. Photo by Vy Dan Tran.

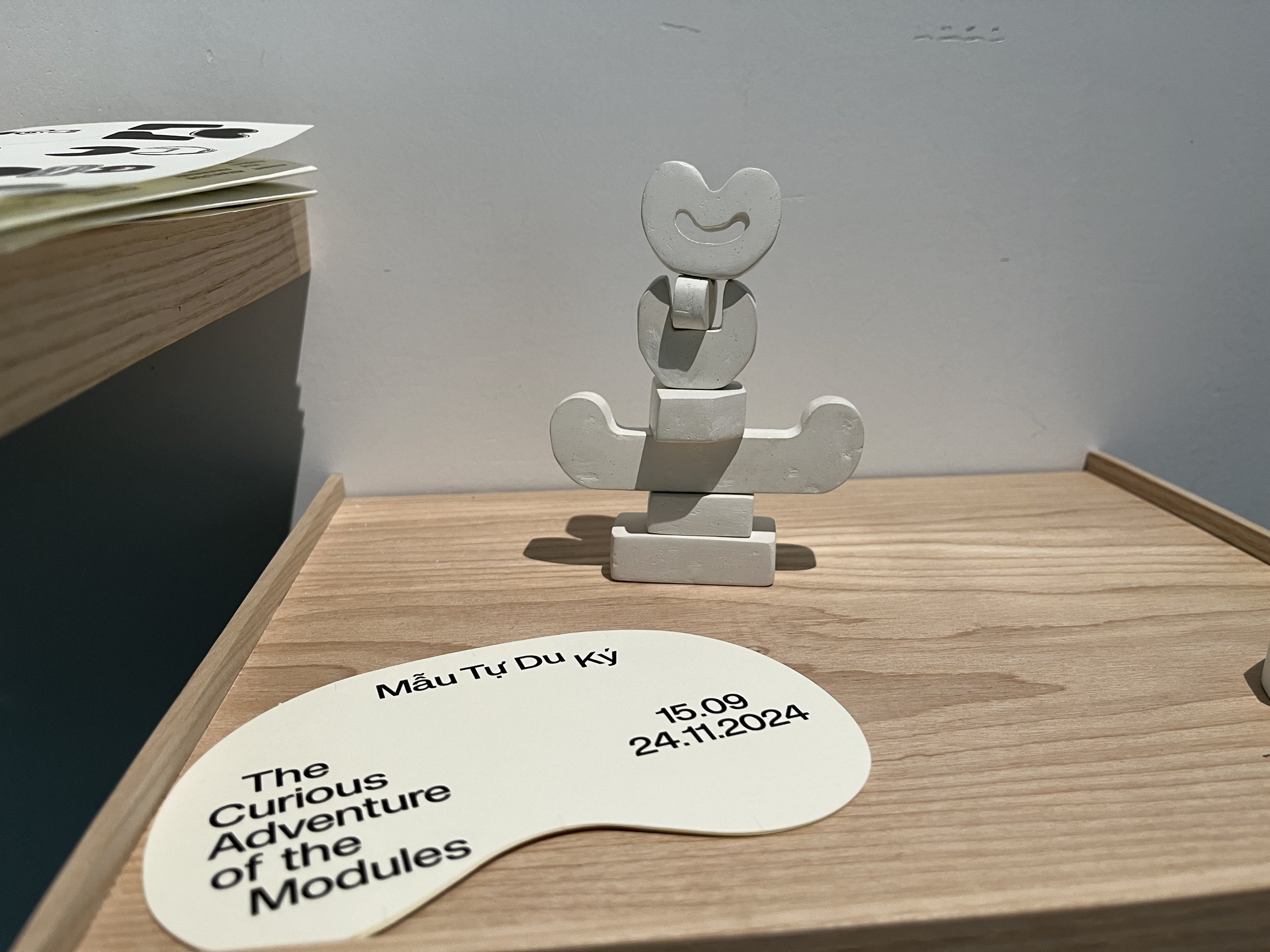

In contrast to the passivity of watching videos, the visitors can also play with white composite replicas. There is one set of ten modules and one set of seven modules, although these replicas are rather small. It would have been more appealing and practical if the organisers could have brought in the colourful modular puzzle educational set designed by the architect Phạm Đăng Nhật Thái. There could also be a label next to the replicas explaining why there are two sets of modules. Initially, the artist worked with 10 modules but later reduced the set into seven, which formed her signature style. It would be helpful for visitors to understand this context.

Archival materials including historical exhibition posters accompanying the show. Photo by Vy Dan Tran.

‘The Modules’ is a creative tribute to Điềm Phùng Thị, an overlooked artist in mainstream Vietnamese art, and it offers a rare chance to explore her work in Hanoi. Neatly curated and nicely lit, this exhibition serves as a starting point to learn about Madame Điềm for those who have not admired her legacy in Hue. Seeing ‘The Modules’ is similar to tasting visual samples; it has a bit of everything including archival materials, sculptures, contemporary video art, and interactive pieces. However, the limitation of The Outpost’s venue as a small private museum also meant that the show was constrained in its ability to explore these sections in depth. There were juxtapositions that did not link up well into an overall cohesive exhibition: modern versus contemporary art, original artworks versus photographs, historical context versus contemporary interpretation. Perhaps a better strategy may be to focus on one thing at a time.

Considering her last temporary exhibit occurred 29 years ago, the original yet obscure sculptor Điềm Phùng Thị deserves a longer retrospective show outside of Hue, where her artworks will be given full attention and investigated in greater depth. ‘The Curious Adventure of Modules’ at Outpost does prompt the visitors to seek Madame Điềm’s multifarious art beyond the museum’s walls,³ and is a good (re-)starting point.

2Đặng Tiến, “Đôi nét về Điềm Phùng Thị”, Hợp Lưu no.10, April & May – 1993.

3For those who would like to see Điềm Phùng Thị’s works outdoor in Hanoi, a large public modular sculpture by her is permanently displayed in Vườn Bách Thảo (Hanoi Botanical Garden).

‘The Curious Adventure of Modules’ was on view at The Outpost Art Organisation, Hanoi, Vietnam from 22 September to 24 November 2024.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect those of A&M.

About the Writer

Vy Dan Tran was born and raised in Hanoi. She graduated in History of Art (major) and Film Studies (minor) from Oxford Brookes University (UK) and completed her Master’s degree in Arts Management at The American University of Rome (Italy). Currently, she translates books, writes for magazines and works as a freelance art critic in Hanoi.