Review of ‘Sewing Discord’ at the Esplanade

Spotlighting craft as contemporary art

By Stephanie Yeap

This is a winning entry from the inaugural Art & Market ‘Fresh Take’ writing contest. For the full list of winners and prizes, click here.

Craft has long been relegated to the domestic and ornamental rather than accepted as “high” art. Esplanade’s exhibition ‘Sewing Discord,’ which takes place from 16 April to 29 August 2021, challenges this by introducing craft’s rich heritages, labour intensive process, and presence in Singaporean contemporary art. Featuring works by five local artists Ginette Chittick, Hazel Lim, Nature Shankar, Berny Tan and Jodi Tan, the exhibition showcases myriad craft techniques and how they articulate ideas of labour, visibility, and agency. With the exhibition consisting of women artists, it is worth considering how the medium of craft has been historically intertwined with the gendering of labour.

Exhibition view of ‘Sewing Discord’ at Esplanade Jendela (Visual Arts Space). Image courtesy of the Esplanade.

Labour — both seen and unseen — is intrinsic to craft and the featured artists interrogate this issue through the lens of process and lived experience. In the online event ‘In Conversation: Sewing Discord’ on 21 May, they spoke about the unseen emotional labour behind working with craft physically. “The physical labour needed mirrors the emotional labour required to go through this whole journey,” Nature Shankar shared. Her practice blends both as the act of assembling and reassembling the threads provides her space to process traumatic racist experiences.

Hazel Lim, ‘The Garden; All Pastels, Twilight behind the Pine Trees; The Dance of the Happy Shade,’ 2021, chromatico paper, acrylic. Image courtesy of the Esplanade.

Hazel Lim, ‘Squaring the Circle,’ 2021, linen, DMC thread. Image courtesy of the Esplanade.

Boasting a rich spectrum of colours and eye-catching textures, ‘Sewing Discord’ is a sensuous experience. Hazel Lim’s intricate woven paper sculptures caught my eye, as they undulate like waves out of brightly coloured acrylic frames. The artist shares in the online discussion that such modular shapes recall the simplicity of square origami, which inspired Lim growing up. Determined to “allow colours to emerge and create monochromatic swatches,” each work reveals new hues as luminous acrylic frames catch the light and cast coloured shadows. Informed by instructional drawings and Jame Elkin’s stance that they are valued as a signifier rather than for their aesthetic, ‘Squaring the Circle’ stems from Lim’s conviction that diagrams “are worthy of being seen as drawings in their own light.” Here, Lim re-contextualises aspects of everyday craft and imbues them with conceptual meaning, shifting away from the hobbyist and instructional associations of craft.

Nature Shankar, ‘Window-view,’ 2021, repurposed fabric, cotton thread, cotton thread, paper, turmeric, dye and graphite on calico. Image courtesy of the artist.

In contrast, Shankar’s works unravel experiences of racism by incorporating hand embroidery and repurposing textiles from both her Chinese and Indian grandmothers. Her practice consists of assembling the threads in a process akin to papermaking, which gives her works a pulp-like texture. Although the process is labour-intensive, its meditative nature allows her to process traumatic events and reclaim agency over them. With historically charged materials and such a cathartic process, works such as ‘Window-view’ enable the artist to give physical forms to her experiences as a mixed race woman while honouring both her heritages.

Ginette Chittick, ‘Echoes,’ 2021, kapok cotton, merino wool, alpaca yarn, acrylic yarn, plywood with pine veneer, corrugated acrylic. Image courtesy of the Esplanade.

Building on Shankar’s practice of making emotional labour visible, Ginette Chittick’s works ‘Echoes’ and ‘This Must Be The Place’ shine a light on the invisible labour of women and their lived experiences. They consist of multiple Shogi screens, from which brightly coloured, cloud-like tufts of various sizes, textures, and materials, such as cotton from local Kapok trees, emerge. Reflecting her role as a mother, Chittick’s choice of furniture proves deliberate as it represents the domestic demarcation of the public and the private, thus recalling how a woman’s labour might go most unnoticed at home.

Close up view of ‘Citations’ (2021) by Berny Tan. Image courtesy of the artist.

Berny Tan’s ‘Citations’ is a series of purposefully illegible works that reflect the invisible intensity and repression of trauma, pain and emotional experiences such as unrequited love. While she frequently incorporates written text in her works, visitors are confronted by a seeming emptiness in ‘Citations.’ Text passages that the artist painstakingly stitched have been unpicked, with only residual fibres serving as remnants of an emotional state that is now indecipherable. This ‘absent presence’ emphasises the invisibility of emotional experiences and how craft might serve as a way to reconcile with and physically preserve them. Hints of the original text lie in accompanying academic citations, which include excerpts from readings such as Griselda Pollock’s work on trauma and aesthetic transformation. In questioning ideas of physical visibility, ‘Citations’ also foregrounds efforts in locating the academic citations that can reflect the artist’s emotional state.

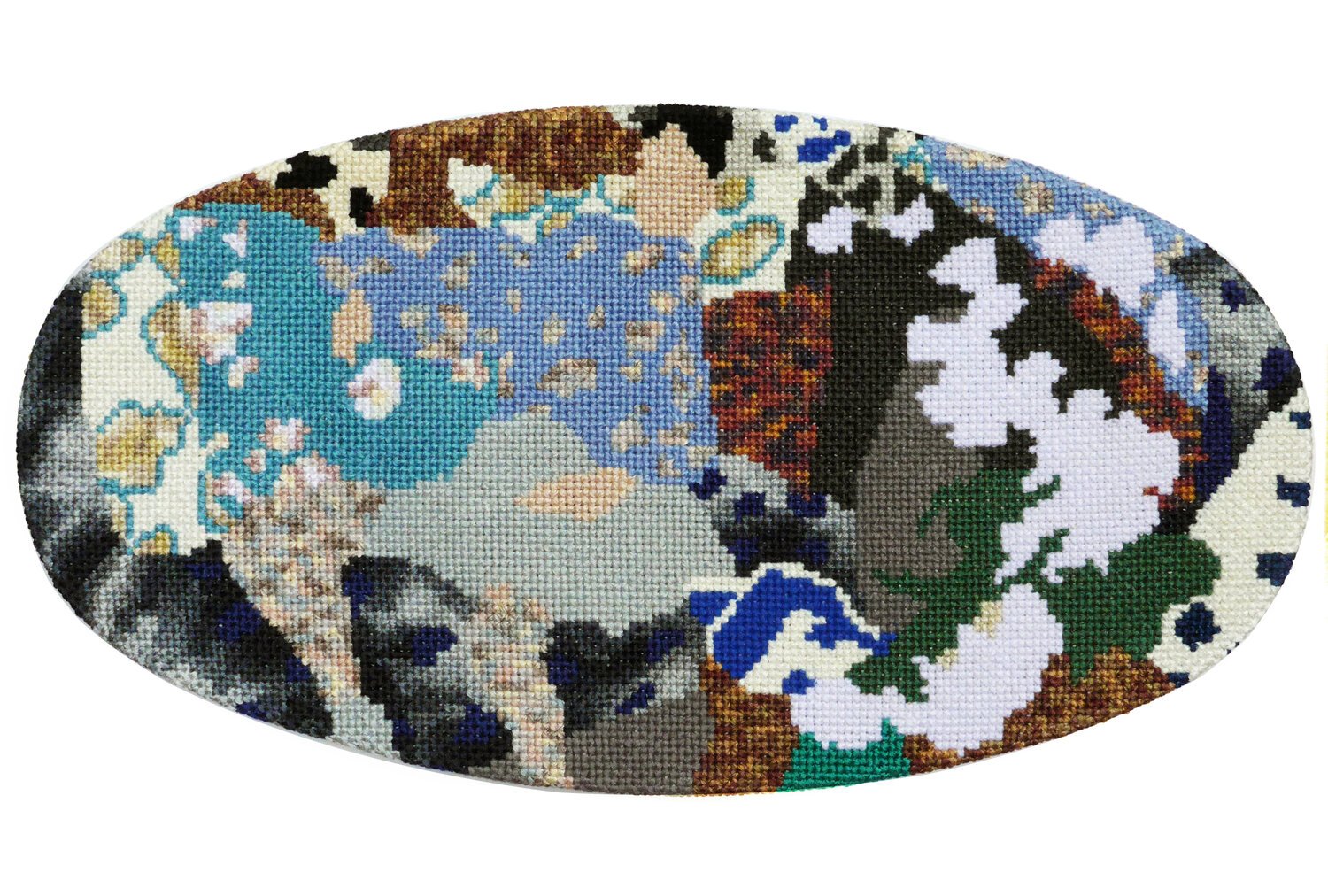

Jodi Tan, ‘Sense of Order #012’, 2016, Cotton floss thread on Aida cloth, 21.5 x 39 cm. Image courtesy of the artist.

The highlight of the show for me was Jodi Tan’s cross-stitch series ‘Sense of Order,’ with most of the pieces measuring 20cm by 20cm. Tan approaches cross-stitch as a painter, resulting in abstract, visually flat works that may not appear aesthetically complex. The simple appearances and small sizes of her works betray the time taken to create them. Tan noted that while she has been cross-stitching for eight years, she has only made 16 pieces because of how time-consuming it is. While the other four artists have cemented craft as a physically and emotionally demanding medium, the slow pace of Tan’s process invites the audience to consider how time might serve as another form of invisible labour.

The mini showcase of each artist’s signature tools was enriching as it encourages viewers to ascertain to which artist they belonged. Nearby, a video plays scenes of artists working. Though brief, Lim tells me that this was deliberate to avoid craft’s traditional, instructional connotations. I found this choice effective as it rendered the creation of the works, which goes unseen until entering the showcase, when it becomes visible. While I initially found the lack of wall text to be curious, I considered the video an effective replacement as it contextualised each artists’ practice.

“Sewing Discord showcases a multi-faceted approach to craft as it reveals how each artist distinctly incorporates personal, emotional, and conceptual associations of craft into their practice. ”

Sewing Discord showcases a multi-faceted approach to craft as it reveals how each artist distinctly incorporates personal, emotional, and conceptual associations of craft into their practice. Ultimately, the refreshing exhibition invites viewers to consider the medium’s unseen relationships with emotions and time, and how the invisible labour of creative processes underpins craft as contemporary art.

The opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed herein are those of author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of the ASEAN Foundation, ASEAN Secretariat, and ASEAN-Korea Cooperation Fund.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect those of A&M.

About the Writer

Stephanie Yeap is a writer based in Singapore. She holds an MA in History of Art from SOAS University of London and is primarily interested in the presence of archival practices in contemporary art.