Review of 'Longings / 寄望 / Jiwa'

Boedi Widjaja and Fyerool Darma at Temenggong Road

By Sara Lau

2019 is a contentious year for Singapore’s history. It marks the Bicentennial, the 200th year since Sir Stamford Raffles landed on the shores of Singapore. When the state first announced this celebration – later corrected as a ‘commemoration’ – reactions from the public were mixed, with many pointing out that Singapore was already a bustling trading port before its “founding” by British colonial powers.

The art world is no stranger to this thorny topic. In 2016, National Gallery Singapore called their fundraising gala the “Empire Ball”, in conjunction with their exhibition, ‘Art and Empire’. Members of the public were outraged at the apparent glorification of colonialism. As Singapore confronts its fraught relationship with its colonial history, so do artists participate in ongoing debates.

Situated in a colonial-style bungalow at 28 Temenggong Road, ‘Longings / 寄望 / Jiwa’ is one such example. Presented by Temenggong Artists-In-Residence Ltd with the support of the National Museum of Singapore, the brief, week-long exhibition features artists Boedi Widjaja and Fyerool Darma. It was conceived as an avenue to explore the themes of migration, representation, and personal longings in Singapore’s history. Its impetus was a donation of a collection of personal letters from Sir Stamford and Lady Raffles and other memorabilia from Tang Holdings to the National Museum of Singapore.

The building itself sets the tone for the exhibition. There is only one way to reach the hilltop bungalow: through a steep, winding road for vehicles, with no footpath in sight. Dense vegetation surrounds the building. Without it, one could supposedly see all the way to the Indonesian Archipelago. Isolated from the city, the bungalow is a time capsule of the 18th century. Previously a site of wealth, power and oppression, it is a most suitable site for the show and its intents.

Boedi Widjaja, ‘Path 10: A Tree (W)(T)alks’, 2019, visual encoding on flags using the semantics of Morse code, dimensions variable, exhibition installation view. Image courtesy of the Temenggong Artists-In-Residence Ltd and the artist.

The artists each utilises one room on the second floor of the bungalow, although Boedi’s work, ‘Path 10: A Tree (W)(T)alks’, first appears on the grounds right in front of the driveway in the form of flags. On first encounter, Boedi’s works reveal little due to their simple, flat structure. They are complex puzzles created through multiple layers of encoding of text into the visual, made in collaboration with geneticist Dr Eric Yap.

At the core of the project is journal text from Boedi’s paternal grandfather, Wu Tong, originally written in Mandarin Chinese. To start , an artificial DNA-sequence is created using a marker from Boedi’s Y chromosome – which transmits patrilineal genes – joined at two ends by a sequenced fragment of the DNA make-up of the Chinese parasol tree, which his grandfather was named after. This genetic code consists of codons that facilitate the synthesis of proteins for 20 amino acids, which are then mapped to 20 consonants in the Javanese language. This is then visually translated using the semantics of Morse code. This work is presented as three flags outdoors, with their counterparts housed indoors. The works ‘Nanyang’ and ‘Jawa’ go through a similar process of transcription. This time, the audio narration of the journal text has been mapped to the I Ching, a Chinese divination system, to produce the images.

Installation view of works by Boedi Widjaja. Image courtesy of the Temenggong Artists-In-Residence Ltd and the artist.

It takes a fair amount of work to unpack and understand these processes, which can appear convoluted. However, the logic and reasoning behind each step taken to create these artworks are what distill their essences: the ideas of visible and invisible cultural inheritances, the connotations of home, territory and belonging, and the plural identities that Boedi constantly grapples with. Works such as ‘Nanyang’ begin to take on new life in the viewer’s perspective: the white spaces against the black grids are akin to the gaps one might find in their personal and cultural histories, and within themselves.

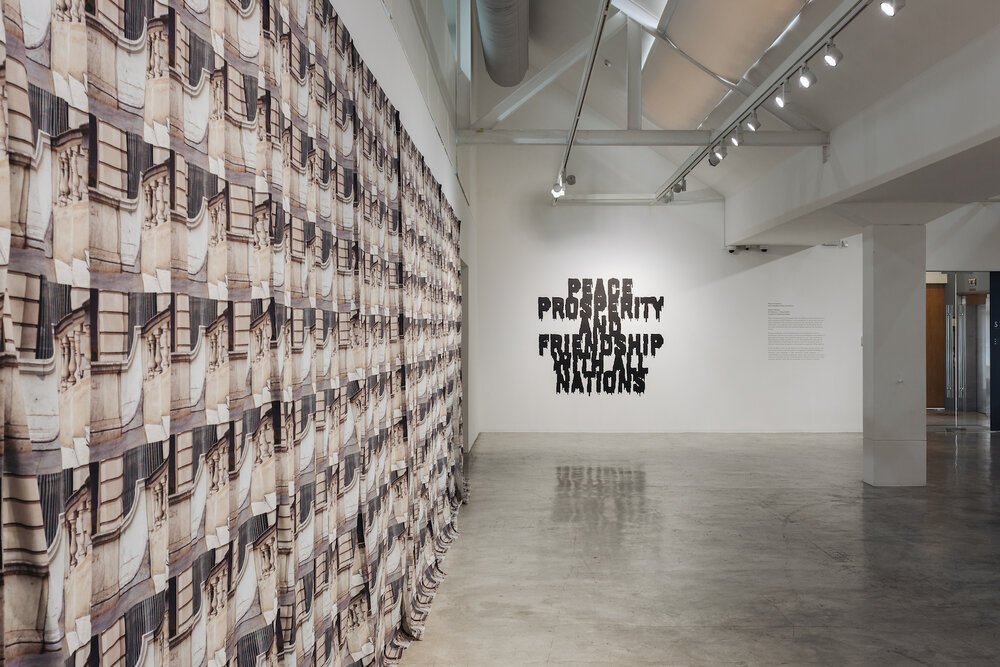

Installation view of works by Fyerool Darma. Image courtesy of the Temenggong Artists-In-Residence Ltd and the artist.

While Boedi’s work is weighed down by its extensive procedures, Fyerool’s artworks appear deceptively simple. ‘The Poseur’ is the next evolution of his series ‘After Ballads’. He has an established visual language that draws from multiple cultural spheres, often employing objects and textiles in carefully composed collages and installations. Those presented in this show are familiar iterations of previous works, such as ‘Sunny, your smile ease the pain’ (2019) at Yeo Workshop and ‘[prep-room] After Ballads’ (2017-2019) at the NUS Museum, employing similar iconography such as palm trees, roses, and a variety of textiles.

Everything pales in comparison to the multimedia installation video at the centre of the exhibition. Adorned with tattoos, the central figure rotates on his axis like a video game avatar, stoic and expressionless. He rotates through several outfits, each more layered than the previous one, to the point where his entire face is obscured by fabric. A ring of emojis circle him, and we see a mix of red and white roses along with yellow sparkles. The backdrop is a saturated background depicting a tropical seascape, comically blue seas and skies with palm trees swaying in the wind. A voiceover reads excerpts from Maria Graham’s ‘Journal of a Residence in India’, which details her encounters with John Leyden’s scribe, Munshi Ibrahim Long Fakir Kandu. The artist’s own text runs across the screen like karaoke lyrics, responding to Graham’s orientalist descriptions of Ibrahim.

Fyerool Darma, 'The Poseur' film still, 2019, video installation with artist textiles, detritus and resin, dimensions variable. Image courtesy of the Temenggong Artists-In-Residence Ltd and the artist.

The installation is nothing short of captivating. The kitschy and campy aesthetics are the crux of the artwork’s subversive nature, confronting the colonial gaze with its own absurdity through the exaggerated tropes of the exotic “Other” in a tropical paradise. It is playful and sarcastic, acknowledging yet mocking in the same breath. It also challenges the viewer to consider their own complicity by using recognisable aesthetics from popular culture to highlight the issues of race and class, drawing a connection between colonial and contemporary perceptions. The strength of the video installation is also the exhibition’s weakness, as the other installations fall by the wayside, adding little to the messages that the video already conveys.

It might seem strange to some that in an exhibition inspired by his letters, Raffles or his words hardly appear at all. Perhaps it was a deliberate choice. After all, the man in question has received more attention than he arguably deserves. As curator and art historian Chang Yueh Siang writes, “These textual finds are taken as another point of departure… the “ephemeral” interacts with the “physical”, providing opportunities to interrogate histories and geographies, to uncover the present, and to enquire into the future.” The works of Boedi and Fyerool turn the exhibition’s impetus on its head, giving voice to unheard narratives and expounding the confluences between personal and political histories. ‘Longings / 寄望 / Jiwa’ provides another avenue to think about historiography and its complicity in political endeavours, and the possibilities of performing public history through artistic practice.

‘Longing / 寄望 / Jiwa’ was on view at Temenggong Artists-in-Residence from 30 September to 6 October 2019.