Interview with Song-Ming Ang and Michelle Ho

Team Singapore at the Venice Biennale

By Ian Tee

Artist Song-Ming Ang and Michelle Ho are representing Singapore at the Venice Biennale Arte 2019. Photo by Olivia Kwok, courtesy of the artist.

The Singapore pavilion at the 58th Venice Biennale is represented by artist Song-Ming Ang (b. 1981) and curator Michelle Ho. Their presentation 'Music for Everyone: Variations on a Theme' takes a series of concerts organised by the Singapore government in the 1970s as a starting point to think about how we relate to music individually and as a society. The exhibition features a three-channel video created with the participation of children following a workshop on improvisation, as well as a series of recorder sculptures and manuscript works created using simple techniques. It proposes inclusive ideas centred in experimental music and conceptual art as counterpoints to state-prescribed notions of music and art.

The collaboration builds on the ongoing dialogue between the duo, who had worked together on a few projects in the past. Both artist and curator have more than a decade of experience practicing, and have been recognised for their work. Ang was conferred the Young Award Award (2011) and was a finalist for the Singapore Art Museum's President's Young Talent Award (2015). Solo presentations of his work include 'Do-It-Yourself' (Camden Arts Centre, London, 2015), 'Logical Progressions' (Fost Gallery, Singapore, 2014) and 'Cover Versions' (Künstlerhaus Bethanien, Berlin, 2012).

Ho is currently Gallery Director of the ADM Gallery at the School of Art, Design and Media, Nanyang Technological University. Prior to this appointment, she was a curator at the Singapore Art Museum, where she led acquisition strategies for its contemporary art collection from 2013 to 2015, and was in charge of its Thailand collection. She has curated ‘Reformations: Painting in Post 2000 Singapore Art' (ADM Gallery, Singapore, 2019), 'Sound & Vision' (Fost Gallery, Singapore 2018) and 'SuperNatural' (Gajah Gallery, Yogjakarta, 2017).

Singapore Pavilion at the Venice Biennale Arte 2019. 'Music for Everyone: Variations on a Theme' by artist Song-Ming Ang and curator Michelle Ho. Photo by Olivia Kwok, courtesy of the artist.

The exhibition's main title 'Music for Everyone' references a series of music concerts in the 1970s by then-Ministry of Culture. I am curious to know how its subtitle 'Variations on a Theme', which connotes difference among iterations, play into the overall concept of the show?

Song-Ming (SM): I discovered the ‘Music for Everyone’ concerts while trawling through music posters from the National Archives, and was intrigued by how the programmes reflected concerns of the Ministry at the time. Fundamentally, it revolved around using Western art music as a syllabus of music education. One could also glean certain agendas like nation-building through folk music and festival concerts, as well as establishing diplomatic relations through concerts involving foreign orchestras.

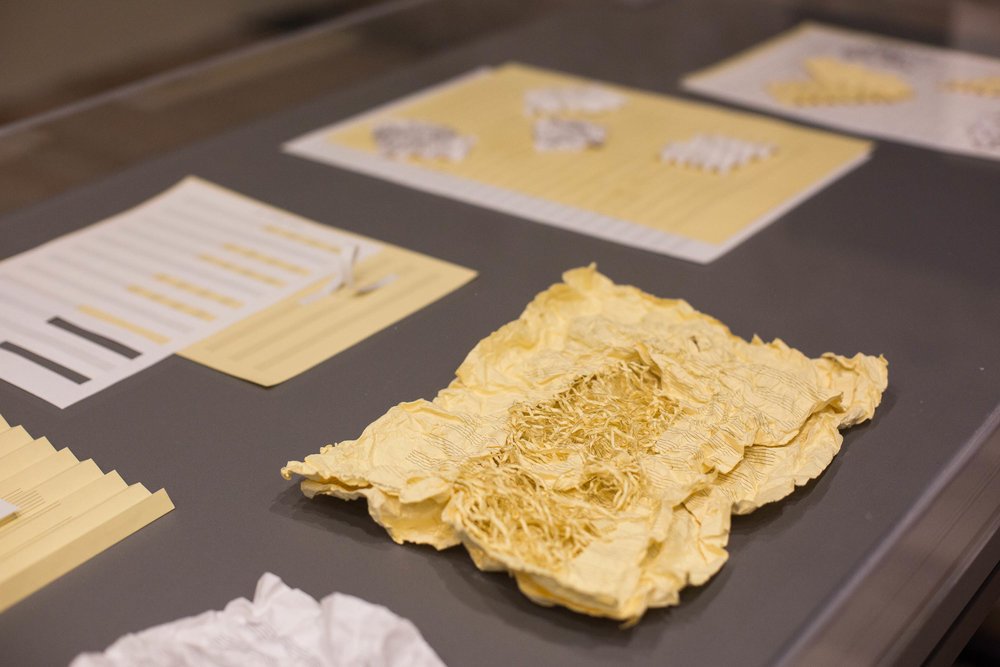

‘Variations on a Theme’ is our own little addition to the title, and it can be seen as an alternative perspective or twist to what was implemented by the state at that time. The variations comprise of artworks that revolve around the ideas of improvisation and play. They are based on a ground-up approach instead of coming from the top-down, employing elementary techniques of art-making. This gives the artworks an amateurish, egalitarian quality. It's important to me that visitors could step into the exhibition and get this feeling that they could have made these artworks themselves, to feel inspired and empowered by the possibilities of working with mundane material like paper and fabric or modest instruments like the recorder.

'Music Manuscripts' at the Singapore Pavilion at the Venice Biennale Arte 2019. 'Music for Everyone: Variations on a Theme' by artist Song-Ming Ang and curator Michelle Ho. Photo by Olivia Kwok, courtesy of the artist.

Did you make any unexpected discoveries about Singapore's music history in your research? What sources did you consult in addition to the National Archives?

SM: The National Archives is a great repository of material. Based on what I have seen, it mostly documented official events so I would not say there was any unexpected material. However, it is a treasure trove in itself for Singaporeans. There are over 2,000 photographs, close to 6,000 oral history interviews and nearly 3,000 audiovisual and sound recordings if you just search for “music” in the online archives.

Of course, we did try to reach out to other sources, and discovered that there are actually more 'Music for Everyone' posters with the National Museum of Singapore. With the help of the National Arts Council, Michelle also managed to get in touch with two ex-Ministry of Culture staff members who worked on the original 'Music for Everyone' series, and interviewed them personally. They helped us with fact-checking and also provided some documentary material and press articles.

'Recorder Rewrite' film at the Singapore Pavilion at the Venice Biennale Arte 2019. 'Music for Everyone: Variations on a Theme' by artist Song-Ming Ang and curator Michelle Ho. Photo by Olivia Kwok, image courtesy of the artist.

The central work in the exhibition 'Recorder Rewrite' is a three-channel film installation which involved the participation of children from various cultural and musical backgrounds. What considerations did you have in framing this engagement and what were the children's responses to the collaborative process?

SM: 'Recorder Rewrite' is an artwork that I’ve been wanting to make for some time. I have always been interested in the potential of the recorder, and thought it would be worthwhile to work with an instrument with such a divisive quality amongst so many people who learnt it in primary school. Partly, I’d say that my motivation is to redress its reputation and find creative ways of re-presenting the instrument. I thought that the best way would be to work with a group of schoolchildren who weren’t necessarily technically proficient on the recorder to show what could be possible.

I was quite intent on formulating a work that synthesised music, visuals and choreography, and to use improvisation and play as ways of creating. Therefore, this formed the film's overriding principle. We ran a two-day workshop for the children to learn creative ways of playing the recorder, and improvisation exercises for them to create their own music. Then, we worked out the choreography on location at the Singapore Conference Hall, and concluded with two days of filming.

Even though it is just a short 15-minutes video, it was challenging to shoot because it’s not a standard film with a storyboard and narrative. We were also shooting with three cameras simultaneously from different angles to create a "symphonic" effect while working with children who had no acting or filming experience. Another issue is that we recorded pretty much all the music on location. There were outdoor scenes with traffic and construction in the background, as well as tricky indoor ones with hard surfaces that caused lots of reverberation. Almost everything required a lot of, well, creativity and improvisation from all the departments. I have to take the opportunity again to thank all 20 performers and 40 crew members for being so flexible and dedicated throughout the process.

Song-Ming Ang at the filming of 'Recorder Rewrite'. Photo courtesy of Dylon Goh for National Arts Council Singapore.

Michelle, you have worked with Song-Ming on four presentations prior to the Venice Biennale exhibition. When did you first come across his work and how this project came about?

Michelle Ho (MH): I got to know of Song-Ming’s practice in the late 2000s, and helped to organise his artist talk at the 2011 Singapore Biennale where we did an impromptu listening party for a public programme. I was very drawn to his practice in terms of how the occasion for art appreciation is also one that is based on the exchange of experiences. This sense of empathy brought about through music resonates strongly in his work 'You and I', which I showed at the Singapore Art Museum in 2014. It consisted of a series of handwritten letters received from the public, which he responded to individually with a customised CD-R mixtape. In 2018, we worked together to develop a new series of work for the 'Rules of Exception' exhibition at the ADM Gallery. In that show, we were dealing with another theme in his practice regarding systems, information and ideas of truth in the post-Internet age. This period of working with him and bouncing off other ideas led to the proposal for the Singapore Pavilion.

How did you navigate the expectations of "representing Singapore" while maintaining criticality within the exhibition? Can you share some of the conversations or negotiations involved in the commission?

MH: We are very heartened that our proposal surrounding the topic of music was selected as Singapore’s submission for the Venice Biennale. This is also telling of how ideas of representation have evolved to encompass the more intangible experiences of our memories with music, and learning about it.

We weren’t conscious about representation in terms of wanting to communicate a specifically “Singapore identity” in the exhibition. That said, 'Recorder Rewrite' and reproductions of the 'Music for Everyone' concert posters convey a Singapore context, along with a sense of history of how music programming was shaped by the state in the 1970s. Audiences are allowed to interpret what this might mean in terms of the relationship between art and control. I would have imagined that the commissioner, the National Arts Council, might have considered these implications. I think it is quite mature on their part to support a project that may bring out these discussions.

The previous two Singapore pavilion presentations, Charles Lim and Shabbir Hussain Mustafa's 'SEA State' (2015) and Zai Kuning's 'Dapunta Hyang: Transmission of Knowledge' (2017), featured overtly political subject matter and expansive regional histories. Both projects came at a time of tension over maritime border disputes and growing interest in an archipelagic framework. In what ways do you see 'Music for Everyone' reflecting current concerns or artistic methodology, especially in relation to the history of Singapore's participation at the Venice Biennale?

MH: 'Music for Everyone: Variations on a Theme' sounds like a simple title, but it also opens up questions such as: who decides what is suitable music for the masses? What were the priorities of early cultural policies in a post-Independence Singapore and have these policies evolved? There are yet subtler dynamics of politics and control that can be read in Song-Ming’s presentation, and he offers a counterpoint within a more egalitarian vision of art and art-making.

'Music for Everyone: Variations on a Theme' is on display at the Arsenale's Sale d'Armi building from 11 May to 24 November 2019.

For more on Southeast Asian national pavilions at the 58th Venice Biennale, read our coverage here.