The Versatility of Video Art in Singapore

Diverse, interdisciplinary and heartfelt

Donna Ong, still of The Forest Speaks Back (I). 2014, single channel video with sound, 5 min 30 sec, edition of 3 + 1 artist's proof. Image courtesy of the artist.

‘Video’ comes from the Latin word 'uideo', which means “I see”. So named, video art takes on a declarative position, expressing what the creator has observed through durational works. The medium requires patience and curiosity, as viewers could either sit through the whole artwork or walk away after watching a snippet.

Singapore artists are increasingly embracing video art, especially at the intersection of photography, dance, and performance art. They have been experimenting with features unique to video, such as pacing, projection, image transitions, voiceovers, subtitles and camera movement. With its time-based nature, I believe the medium’s versatile and interdisciplinary character opens up possibilities for knowledge production and provides viewers with an immersive experience to gain new insights.

Documenting the Unfamiliar Familiar

Donna Ong, still from The Forest Speaks Back (III), 2018, single channel video with sound, 5 mins 31 secs, edition of 3 + 1 artist's proof. Image courtesy of the artist.

One striking method is the juxtaposition of photographs to highlight unexpected connections. In January this year, FOST Gallery presented Somewhere Else: The Forest Reimagined, a solo exhibition by Donna Ong. The artist showcased part I (2014) alongside part III (2018) of her work The Forest Speaks Back. While part I is a film showcasing 18th and 19th-century lithographs of the tropical forest, part III displays photographs of artificial environments such as gardens, greenhouses and zoos. Though captured over 100 years apart, both types of images perpetuate colonial ideals of the tamed forest.

The Forest Speaks Back is not a conventional recording but rather presents towering slideshows of archival and photographic images. Ong explains, "Video projection allows the images to be enlarged, offering an immersive space where audiences can compare their experiences in the real jungle to these artificially constructed environments." She adds, "The medium also allowed me to curate, sequence and provide a smooth transition from one image to the other, lulling the viewer into an almost dreamlike state." Indeed, when I saw the work in person, I was pulled into its slow rhythm and would, at times, fail to realise that the image had already changed. Ong’s purposeful use of pacing pushes the viewer to see just how similar the lithographs and photographs are; they feature lush but neatly arranged foliage, positioned to spotlight star features like waterfalls and ponds.

Dave Lim, still from The Believers, 2020, video installation, 16 min 1 sec. Image courtesy of the artist.

Dave Lim and Adar Ng, still from The Spaces Between Us, 2021, video installation, 19 min 31 sec. Image courtesy of the artists.

Another set of works that use juxtaposition to maximise what the video medium offers is The Believers (2020) by Dave Lim and The Spaces Between Us (2021) by Lim and Adar Ng. Instead of placing contrasting images side by side, these works splice videos of everyday life together. The Believers juxtaposes secular and non-secular rituals by Singaporeans, revealing a common humanity among different identity groups. Commissioned by the National Museum of Singapore, The Spaces Between Us provides a glimpse of the various experiences during the pandemic, inevitably affected by a person's age, ethnicity, religion, and socioeconomic status. In this work, we see how migrant workers could be looking outside the window of their tightly-packed dormitory while a child slurps a bowl of noodles at school and a couple holds a wedding ceremony over a video call, thus revealing the disparity of livelihoods within this small nation.

Why do artists choose this method of juxtaposition? “My art process is rooted in the creation of empathy through seemingly contrasting places,” Lim elucidates. “For me, the video is a formalistic experience that takes after photographers Bernd and Hilla Becher's Water Tower series. It is in this formalism that we can get close to teasing out differences and similarities.” Consistently, the scenes in both works by Lim and Ng employ similar formal qualities. They are shot from afar in a single perspective without additional camera movement. As such, it is easier to compare different scenes. Without being distracted by new formats, our eyes start paying attention to the details, allowing us to understand and sympathise with different perspectives.

Min-Wei Ting, still from Hampshire Road, 2019, video, colour, sound, 7 min 4 sec. Image courtesy of the artist.

The single-take, slow-panning video work Hampshire Road (2019) by Min-Wei Ting demonstrates a straightforward but effective way of encouraging observation. I encountered the artwork in 2021 during OH! Jalan Besar: Refuge for Strangers, an art walk around Jalan Besar by OH! Open House. The participants and I were led into a minibus, which journeyed around the area while we watched Hampshire Road. Ting trailed his camera along the Little India bus terminal for seven minutes. In the video, migrant workers wait in long monotonous lines for shuttle buses to their sleeping quarters. After the video ended, the minibus drove by the same terminal in less than a minute, showing how easily one could ignore such a scene. The slow pace in Hampshire Road forces viewers to come face to face with lifestyles we may choose to disregard in daily life.

Ting’s employment of a single-take video emphasises the architectural qualities of the captured bus terminal. Influenced by the Little India riot in 2013 at Race Course Road and Hampshire Road, the building is equipped with cameras, yellow queue lines, see-through fences and a group of policemen at its tail. Nothing can be hidden from view, whether from Ting’s camera or the police cars circling the area. “I feel that the work has become more salient given the harsh conditions migrant workers have been and are still subjected to,” ruminates Ting. “The building depicted in the film has been unused since the start of the pandemic, underscoring how dramatically life has changed for them.”

Collaborating in Education

Zulkhairi Zulkiflee, installation view of Proximities, 2022, video.

Taking an academic approach, Zulkhairi Zulkiflee's Proximities (2022) uses the format of an essay film to present its main points. Part of Zulkiflee's first solo exhibition at Objectifs this year, the work explores Malay masculinities through the trope of the Malay Boy depicted by Nanyang artist Cheong Soo Peng. As if giving a presentation, a voiceover provides context, poses questions and proposes new ideas. The voice focuses on the word 'trope', which comes from the Greek word ‘tropos’, meaning ‘to turn’. It then suggests a turning away from mass-propagated stereotypes and a turning towards individual voices.

What differentiates Proximities from typical essay films is the inclusion of choreographed scenes and dance performances by collaborators found through Instagram. These segments are not clearly explained, leaving room for the viewer's imagination. “My collaborators’ video posts on Instagram influenced how the scenes were put together,” Zulkiflee expounds. “They embody a form of creativity as people that aligns with mine as an artist, and I felt like I was working with who they chose to be.” This organic mode of collaboration, where each performer has a space to express themselves, works well with the idea of turning towards individual voices. As a collaborator turns his body in dance, we are pushed to interrogate the underlying power systems that come with the representation of Malay bodies.

Farizi Noorfauzi and Nelly Tan, still from XxHaven_KitchenxX, 2022, video, 11 min 33 sec. Image courtesy of the artists.

The work XxHaven_KitchenxX (2022) by Farizi Noorfauzi and Nelly Tan adds a playful twist to the format of an instructional cooking video, now popular on social media. The work celebrates nonsensical forms of knowledge and questions the idea of “bad” cooking. Without a precise recipe, hands are shown drying winter melon seeds, chopping pickles, peeling cucumber skin and more. "I was thinking about the formative aesthetics in easy DIY craft videos and internet how-tos," articulates Noorfauzi. “Our video tutorial functioned as a backdrop to our conversations about cooking, failure and braving individual fragilities.” Indeed, rather than instructional voiceovers, the video employs subtitles of these authentic conversations. They discuss illuminating thoughts, such as an idea to increase the quality of failure instead of reducing its frequency. Subverting the goal of creating a perfect meal in usual video tutorials, the work talks about the joy of making mistakes.

The durational aspect of XxHaven_KitchenxX foregrounds the laborious and time-consuming process of cooking. The video work was shown as part of the group exhibition 'Fated Love Sky', initiated by Chand Chandramohan and Racy Lim, which promoted healing in art-making. In this vein, the work presents cooking as an overlooked act of care. “Food is often taken for granted due to its accessibility in Singapore, and yet it is a privilege to many others,” reflects Tan. “There was a lot of mutual care shown between Farizi and I to make the process as fun as possible. We kept bouncing ideas off each other till we had to pull back because some parts were becoming quite outrageous.” For Noorfauzi and Tan, who did not know each other before the show, the collaborative process was one of connection, acceptance and good humour through food.

Exploring the Performing Body

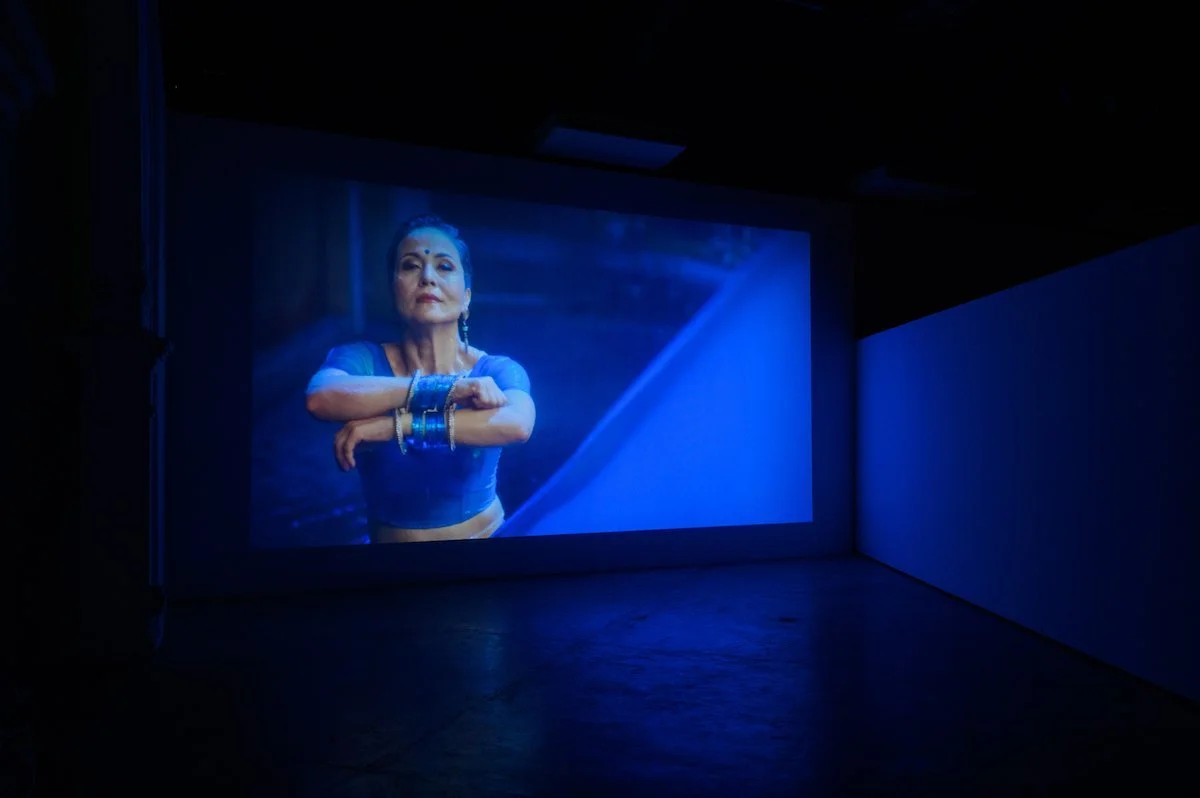

Kanchana Gupta, still from Production of Desire - Take #003, The Gaze, 2021, single channel video installation, 5 mins loop. Image courtesy and copyright: Kanchana Gupta.

The video medium often takes on a documentary function in performance art. Many artists, however, use a combination of video and performance to directly challenge television tropes. Take Kanchana Gupta's performance-based video series Production of Desire (2020-2021), which references the archetype of the sensuously gyrating female body created by Indian cinema in the 1980s and 1990s. Confronting, subverting and reclaiming this constructed image, Gupta presents her own body in an exaggeratedly fetishised manner and uses codes of Indian cinema: chiffon sari, rain, jewellery, provocative movements, suggestive songs and camera angles foregrounding specific body parts.

Gupta takes advantage of the video medium to act as its creator, performer and viewer all at once. “This is a deeply personal series where I assess my own desirability against these cinematic tropes, especially in my vulnerable teenage years,” intimates Gupta. “Video is the best medium to explore the complex relationships between the viewer and performer. While the power clearly lies with the viewer, I intend to shift the agency to the performer, deploying my own body and gaze.” Indeed, when I experienced the works at the duo exhibition While She Quivers, curated by Kimberley Shen this year, I was struck by Gupta's penetrating gaze at the camera. It was as if to say, “I know exactly what I am doing, and what you are seeing.” Truly, Gupta's character is an active force, aware of the misconceptions surrounding the female body, too often presented as a spectacle and an unassuming desirable object in the media.

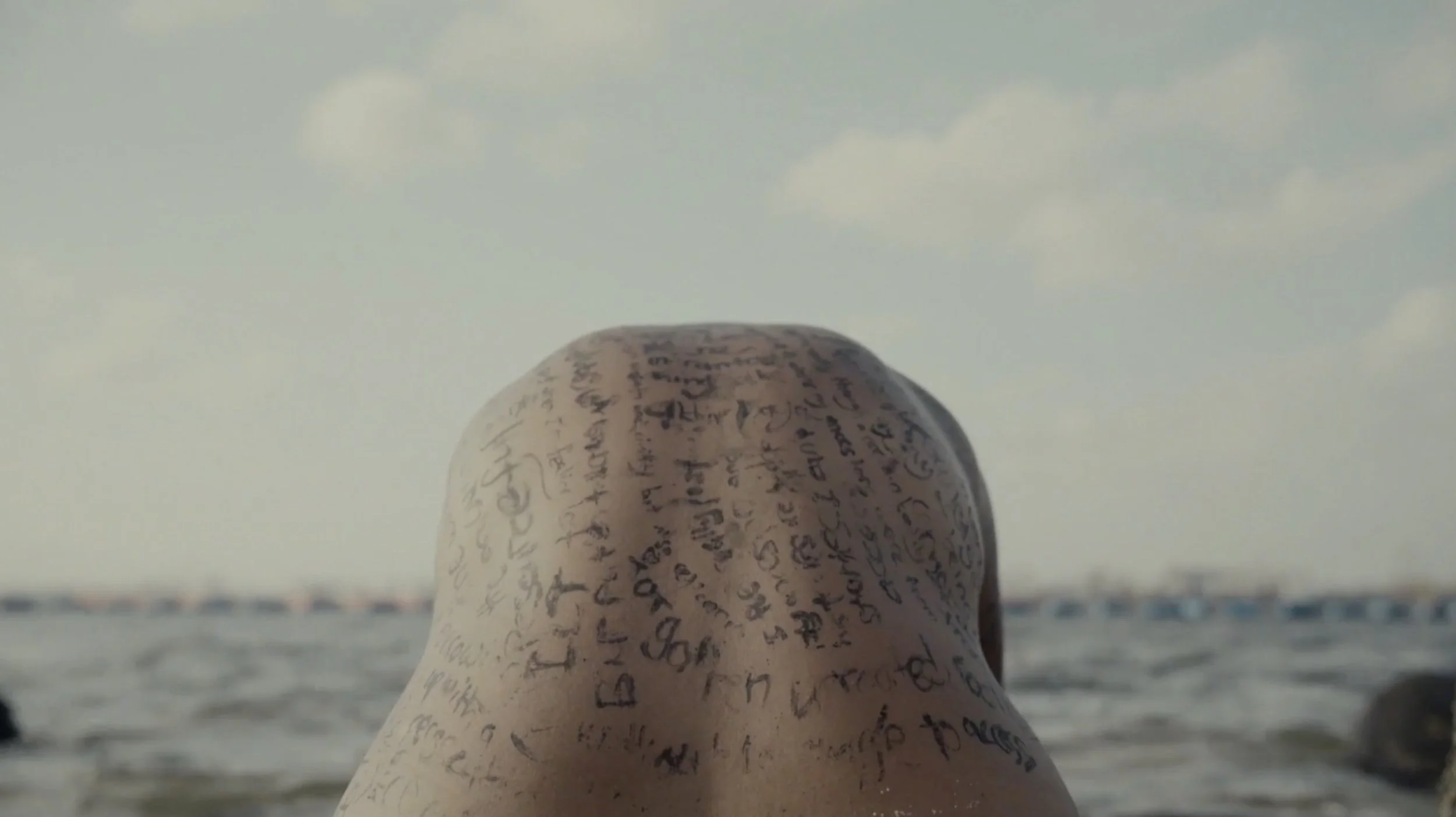

ila in collaboration with Kin Chui, still from bekas, 2019, single channel video installation, 13 min 38 sec. Image courtesy of the artist.

In bekas (2019), artist ila makes use of video to capture performance art in multiple locations, which are important for the work. Created in collaboration with Kin Chui, the short film was exhibited as part of Arus Balik – From below the wind to above the wind and back again at NTU Centre for Contemporary Art Singapore in 2019. In the video installation, ila inscribes text on her bare body and exposes herself to the hot air, sand and sea on reclaimed lands in Singapore. The text narrated ancestral lineages from ‘Malay Singaporeans’, a colonial racial category that muddles the diverse Batak, Boyanese, Buginese, Minangkabau, and Javanese cultures that exist within it. As the body sweats in response to the humidity of the tropics, these texts similarly dissolve into illegible traces. Performed on reclaimed lands, the site-specific performance likewise reminds us of the numerous communities lost due to land expansion.

The video medium compels viewers to focus on subtle details in performance art. The Malay title ‘bekas’ translates to the adjective ‘former’ and the noun ‘remains’ or ‘container’. In bekas, the body attempts to contain the memories of their identity, appropriated and forgotten in post-colonial times. “Within the video, viewers may experience the tactility of bodies and environmental elements,” expresses ila. “As someone who started with live performance art, my body has always been a medium to provoke and disturb; my movements in bekas are reactionary to the context in which I have placed my own body.” Certainly, the close camera angles reveal her genuine discomfort and primal responses to the environment in these reclaimed locations. Rather than a distinctly feminine figure, the body in bekas appears more like a landscape, holding personal experiences and the weight of multiple communities.

Selling Video Art

Zulkhairi Zulkiflee, installation view of Proximities, 2022, video.

Given the sophisticated ways that artists are using the video mediums, from juxtaposition to education to performance, is there an audience for video works? Indeed, video’s digital and often installation-based nature makes it seem difficult to collect. “It may be due to a lack of visibility,” suggests Ting. “There are specific demands of not just showing but also storing video works due to technological obsolescence.”

One challenge in the sale of video works is their ease of dissemination. To control their distribution, many artists make their video works available in editions of five or less. Both Ong and Zulkiflee put up their artworks in editions of three. They also prefer to know the collectors who are purchasing their works. This is in part to make sure that the works will be properly cared for and displayed according to their installation needs.

Dave Lim, still from The Believers, 2020, video installation, 16 min 1 sec. Image courtesy of the artist.

In addition to the video work itself, artists sometimes include documentary material in a sale. Lim, for instance, would sell his work The Believers with a tour to one or two of the sites shown in the film. Cognizant of the medium’s many possible formats, he and Ng would also include one exhibition and one archival copy of their video works. Similarly, ila would pack her artworks with behind-the-scenes material such as sketches, photographs taken on location, a script and other reference material in a box. Possibly due to the medium’s complexity of preservation and display, she observes that video works are usually acquired by institutions such as museums or commercial galleries rather than independent collectors.

Despite its challenges, the medium has gained more recognition over the years due to its acceptance by both collectors and artists. “I think the sale of video as a medium is growing, and many collectors prefer to buy video works,” posits Gupta. “I don't see the medium as a limitation for sale.” Along similar lines, Tan raised that non-fungible tokens (NFTs) have become increasingly popular. “Many creatives have been getting on board during the lockdown, when there was a boom of digital art being made and shared across the world,” she affirms.

From the perspective of an audience member, there have been diverse, innovative and heartfelt video works exhibited in Singapore over the last few years. The medium can emphasise the strengths of other disciplines, as shown through Ong’s slow transitions between detailed photographs, Zulkiflee’s layering of voice overs over expressive dance movements, and ila’s employment of camera angles to focus on delicate motions in performance art. Through its unique qualities, the medium can also encourage audiences to reevaluate everyday experiences. Lim and Ng’s use of juxtaposition, along with Min’s one-take film, highlight the differences of livelihoods within Singapore; Noorfauzi and Tan’s work subverts the format of the instructional video to embrace failure; and Gupta’s gaze into the camera lens confronts traditional tropes in Indian cinema. While the market for video art may still seem to be in its nascent stage, I believe that the rise of the metaverse and the appetite of artists to generate new knowledge are promising for the medium’s long-term sustainability in Singapore.

This essay was first published in CHECK-IN 2022, A&M’s second annual publication. Click here to read the digital copy in full, or to purchase a copy of the limited print edition.