Review of 'Shaping Geographies' at Gajah Gallery

Wulan Dirgantoro, Michelle Antoinette, and Southeast Asian women artists

By Ian Tee

Anida Yoeu Ali, 'White Mother #1' (Concourse), 2014, digital inkjet print on archival paper, 112.5cm x 75cm. Image courtesy of Studio Revolt.

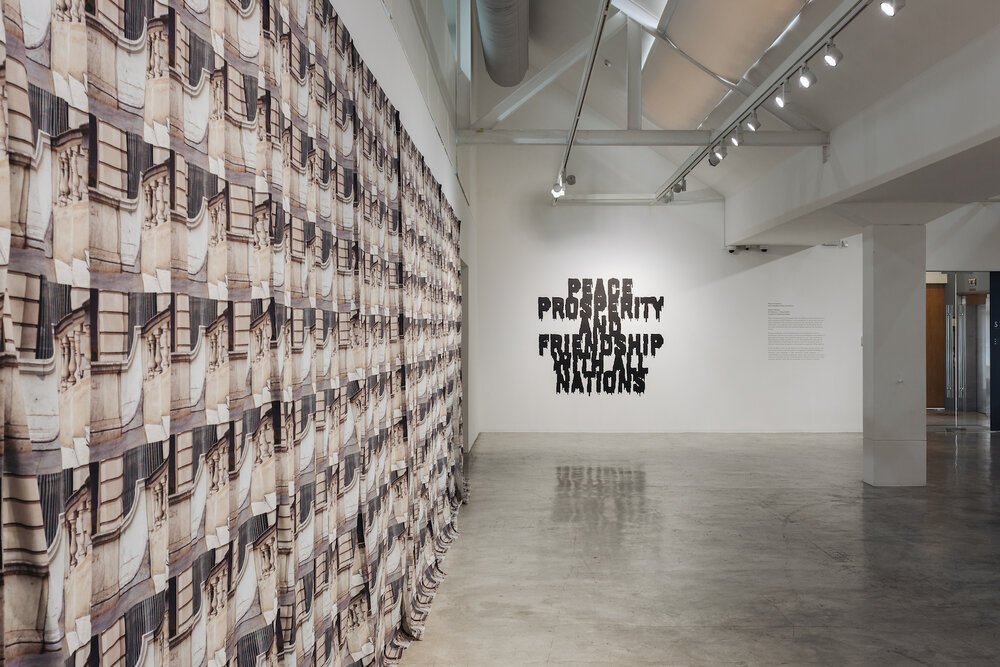

Gajah Gallery closes 2019 with an ambitious exhibition more than a year in the making. Titled 'Shaping Geographies: Art | Woman | Southeast Asia', it is curated by Michelle Antoinette and Wulan Dirgantoro, two prominent art historians working in the field of Southeast Asian contemporary art. It features an intergenerational group of 11 contemporary female artists whose works span across a variety of mediums, methodologies and subject matter.

Connecting gender and geography, the curators are interested in the idea of "intimate geographies as a way of understanding the region through proximities and the personal". For Dirgantoro and Antoinette, the intimate is a framework for rethinking and challenging larger political ideologies such as the geopolitical construct of Southeast Asia. Their academic backgrounds are also evident in the exhibition essay, which foregrounds significant exhibitions of Southeast Asian women contemporary artists, such as 'Womanifesto' (Thailand, 1995-2008), 'Women Imaging Women' (Philippines, 1998, 1999) and 'Text and Subtext' (Singapore, 2000). In this regard, 'Shaping Geographies' distinguishes itself through emphasising a new direction and alternative urgency for many women artists rather than seeking to rediscover forgotten works in mainstream history.

Geraldine Javier, 'Seascape (Blue Hour II)', 2019, ink transfer, finely cut plastic, acrylic, encaustic on wood, aluminum laminate, 275 x 183cm. Image courtesy of the artist.

Geraldine Javier, 'Seascape (Blue Hour II)', 2019, ink transfer, finely cut plastic, acrylic, encaustic on wood, aluminum laminate, 275 x 183cm. Image courtesy of the artist.

It is a curatorial framework that serves well for complex micro-narratives to emerge. However, the flexibility can also be seen as a lack of structure for the exhibition. Even though there are overlapping themes across the works on show, the display does not intuitively guide viewers through them. Potential dialogues and lines of sight are broken to accommodate larger installations as well as other works that fit into specific spots. Indeed, Gajah Gallery's space is challenging, with awkward shaped rooms joined in one continuous layout.

Therefore, 'Shaping Geographies' may have benefitted from a tighter edit. In fact, the point made about collaborative or community-based practices is layered enough to fuel further exploration into a standalone show. Works by the Muslimah Collective speak to the reality of living in conflict-ridden Patani, while Geraldine Javier's new paintings and "pool" installation of finely cut plastic bottle rings respond to environmental pollution by transforming waste through labour intensive processes. Just as Javier's practice shifted after moving out of Manila into Batangas, Yee I-Lan's latest tikar works also mark a new direction since she relocated back to her hometown in Sabah. Created in collaboration with local weavers, Yee reflects on this everyday utilitarian object as a performative space, saying: "When laid on the ground, it invites a gathering of some sort… holding people together, to commune."

Suzann Victor, 'Promise', 1995, human hair, velvet, bread, woks, baby rocker, dimensions variable. Image courtesy of the artist.

Suzann Victor, 'Promise', 1995, human hair, velvet, bread, woks, baby rocker, dimensions variable. Image courtesy of the artist.

Another approach that could have been taken is to chart the development of specific women artists across time, though only Suzann Victor is given this treatment. The Singapore artist has two works in the show: a 1995 installation 'Promise', restaged for the first time in Singapore; and 'She Is Closer Than You Think' (2019) which depicts her friend's grandmother who was a "comfort woman" during the Japanese Occupation. The painting is obscured with circular Fresnel lenses that distort or magnify sections of the image. Their surface also displays burnt cracks or tributaries, which allude to broken bloodlines and the idea of transgenerational trauma. Both works bear witness to histories of violence against women's bodies, connecting Victor's personal vocabulary of symbols with larger narratives that are censored in the public sphere.

IGAK Murniasih, 'Aku Susah Bernapas', 2000, acrylic on canvas, 90 x 95cm. Image courtesy of Gajah Gallery.

Rightfully, the contributions and voices of women can no longer be ignored. "The emergence of Southeast Asian women artists is not new, however, it is only now that industry professionals are paying more attention to them," comments Gajah Gallery Director Jasdeep Sandhu. "The general perception of a woman artist as performative or superficial compared to a male artist may be reflected in the art market. But the demand for works by women artists is increasing and I think that progress is long overdue." Sandhu also notes that the exhibition is an opportunity to build a show around the artists they are in contact with, while introducing exceptional talents such as the Muslimah Collective whose works had never been exhibited in Singapore till this show.

In spite of its limitations, 'Shaping Geographies' is an inspired endeavour which sought to highlight shared concerns and approaches by Southeast Asian women artists. There are multiple strands in the show that can be further developed to illuminate narratives absent in art history. Thus, it is especially commendable that a commercial gallery is putting their weight behind such an initiative, not only growing a market and audience for these works but also supporting new scholarship. Even as new opportunities arise in today's socially-conscious climate, Dirgantoro and Antoinette remind us, "The demand for equality should also be maintained otherwise it is easy to continue the illusion that everything is working now for women artists." The responsibility for this task falls not just on females, but also their male allies.

‘Shaping Geographies’ is on view at Gajah Gallery from 22 November till 31 December.