Midpoint: Sherman Mern Tat Sam

Criticism as a form of activism

By Ian Tee

Midpoint is a monthly series that invites established Southeast Asian contemporary artists to take stock of their career thus far, reflect upon generational shifts and consider the advantages and challenges of working in the present day. It is part of A&M Dialogues and builds upon the popular Fresh Faces series.

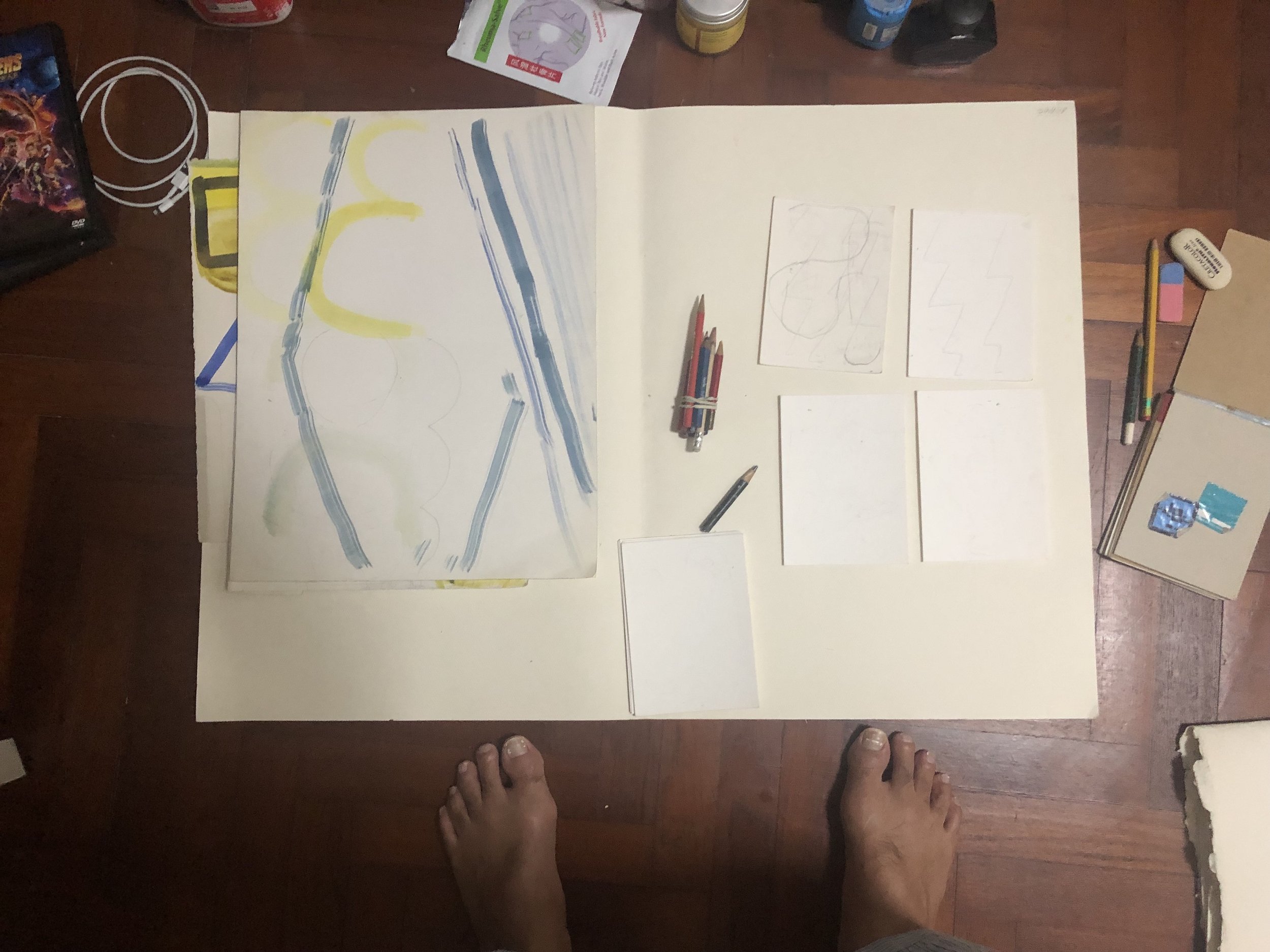

“In Singapore, my studio is my bedroom floor from which I draw. It is about a metre by a metre.. just enough space.” Image courtesy of the artist.

This month’s guest is Sherman Mern Tat Sam. Born in 1966 in Singapore, he is an artist and critic living and working in London and Singapore. Sherman’s intimately-sized abstract paintings and drawings have an improvisational quality, with forms that unfold over time. He describes them as “slow objects for a speedy world”. He was contributing editor at www.kultureflash.com, and has written for Artforum, The Brooklyn Rail, and various British art magazines.

In this conversation, Sherman speaks candidly about his formative experiences, his thoughts on the differences between art writing and criticism, as well as what it means to think of art as a way of life rather than profession.

Sherman Mern Tat Sam, ‘Walk on by..’, 2006, oil on panel, 25.4 x 21.8cm. Image courtesy of the artist.

Could you share a decision and/or event that marked a significant turn/moment in your path as an artist?

I went to the Parsons School of Design. At the time, in 1987, there were three branches: New York, Paris and Los Angeles. I was in Paris, but I took a course with a teacher from the LA branch in the summer of 1988, Robin Vaccarino, who recently passed. She convinced me that LA was the place to be. Take note, they say this about LA every two decades or so... That small piece of serendipity changed everything for me. After that, I understood that there are many artworlds and many kinds of artists depending on where you are. For example, East Coast art versus West Coast art, which from afar just all seems like American art. But also that there can be a right and wrong place for you and your art… I always think I’m in the wrong place. Ha!

I also learnt that what is represented in the news only presents a small slice of reality. For instance, riots in Paris tend to happen within a few blocks, and life goes on as normal for everyone else. Likewise, when you read about what is happening in art, it is highly limited by where the eye of coverage falls. There are many, many artists inventing interesting things that editors, for one reason or another, do not think are as interesting as you do.

Sherman Mern Tat Sam, one-person show at The Suburban, 2007, exhibition view at the Suburban, Chicago. Image courtesy of the artist.

‘Slow Painting’, 2019-20, a Hayward Gallery Touring exhibition. Installation view at The Lewinsky Gallery, Plymouth. Photo by Alan Stewart.

When have been milestone achievements for you as an artist, and why have they been particularly memorable?

I consider my solo exhibition at The Suburban in 2007 my first grown-up show. It is the artist, writer and curator, Michelle Grabner’s project space in the suburbs of Chicago, which has since relocated to Millwaukee. I made works that were hand-luggage sized. Prior to that, pieces that size were little “practice” studies on off-cuts of panels; things that were done for the movement of the hand. But I made one that felt just right. In that, I mean I sensed it could become a painting. This grew into ‘Walk on by..’ (2006). Those works showed me the way. Why bother with big paintings when you can fit it all into hand luggage, metaphorically speaking? That winter was the coldest in Chicago then, and The Suburban is a pretty hands-on place. So I was handed a hammer and nails, and got on with it. All in all, it made for a very memorable show.

I think the best shows are the ones that come about when you have not agitated for it. Someone knows you or your work, and they put you in something. Two recent opportunities came about that way: the Hayward Gallery touring exhibition ‘Slow Painting’ (2019-20), curated by the critic Martin Herbert; and my forthcoming two-person show at Kingsgate Project Space, organised by Dan Howard-Birt.

Could you walk us through a typical work day, or a typical week? What routine do you follow to nourish yourself/your artistic practice?

I think for creative people, rhythm is very important; rhythm in work, rhythm in life. I have, and like, a disrupted rhythm, so I feed and fight that. I tend to paint at night, vampire time, but on a good day I spend a lot of daylight looking or glancing at the work while trying to tidy up my space. This usually results in more mess though. You know you have to build up heat to paint. Waiting is important; I feel that today we are in too much of a hurry all the time. One part of my annual routine is to make my panels in the summer.

I do yoga, read (philosophy, art history, comic books, airport junk), watch football and read about it. Reading football criticism is a big diversion. Everyone should get a football team! Because you know your suffering ends once a year, and then you get to do it all over again. On a weekly basis you get to end the week on a high... or have to wait a whole week to be happy. Actually I think it is a kind of male soap opera. It provides a nice distraction from our over-serious industry–I say over-serious because we do not save lives, prevent violence, stop wars or make peace, etc... I am not denigrating it but… Better yet, everyone should practise yoga or some martial art or body work. It makes a nice complement to being an artist. Making art is a kind of awareness work, so working on body awareness is also enriching. I practise yoga a couple times a week, either at a studio or at home. When I get annoyed with art people, it is refreshing to hang with yoga people and vice versa, because you know they can all be really really really annoying!

Once a week I see a good painter friend and we look at shows, discuss and analyse the work. I keep saying we spend more time dissecting the bad stuff, of which there are many, than the good things. He says, “they’re good, what’s there more to say…” Ha! On a good day, after wading through all this rubbish, I think I am a genius. On a bad day, I think I will never have success. But it is important, especially as you get older, to be reminded that what you do is not where it is at. I think it is important to have a sense of what is going on and how things are changing. Information you get through devices, digital or analog, is mediated. It is important to see work unmediated.

Finally, and most importantly, since I live where I work, I go out for coffee every morning.

“Information you get through devices, digital or analog, is mediated. It is important to see work unmediated.”

Sherman’s studio in London. Image courtesy of the artist.

“My studio floor is a carpet that I found in a skip decades ago. It has been in my last four or five studios.” Image courtesy of the artist.

Could you describe your studio and how it has evolved over the years to become what it is today? What do you enjoy about it, and what do you wish to improve?

Well, I have been in this studio since around 1999. First, it was empty and now it has become a lot fuller... I blame collectors and museums! I face one wall where I paint, and eventually the finished works move to the wall behind me. My studio in London is where I also live. It is open plan, so the studio becomes a live/eat/writing space and kitchen. The result is I can look at my work blurry-eyed every morning, while trying to wake up. At any point in the day, no matter what I am doing, I can take surreptitious glances at the paintings that are growing. Also, my studio floor is a carpet that I found in a skip decades ago. It has been in my last four or five studios.

The football manager Jose Mourinho said that at Chelsea, he practised transitions each week; transitions from attack to defence for 2 days, then from defence to attack for two days, etc... I feel that my studio/living situation moves from chaos to order and then from order to chaos, sometimes all that in a single day.

In Singapore, my studio is my bedroom floor from which I draw. It is about a metre by a metre.. just enough space. You could say that, for now, I paint in London and draw in Singapore.

How could things improve? A bigger space.. but isn’t that what everyone says? I hear that Imi Knoebel uses a three-storey factory building as a studio. Now that would be nice. Actually I would rather have my front door open onto the sea. There is nothing like a morning walk on the beach. Every year I try to take a beach vacation; same beach, mostly same restaurants, same coffee shops. It makes things boring. Baldarssari once said that he only made art when he was bored. I agree with him. I think boredom encourages the creative juices, but we live in a moment when we can easily stave off boredom. It is so important to get nourishment.

In addition to your artistic practice, you are also a prolific writer. During an artist talk with Ian Woo, you brought up the “problem” of not fitting into neat categories. How have you navigated the identity of wearing multiple hats? Were there moments in your career when you felt that this was challenging, or even disadvantageous?

I think there are two not-fitting-in problems that I mentioned.

The first is what you are alluding to: painting and writing. It seems in our industry, it is difficult to conceive of artists who write criticism, despite the fact that there have been many. Or for that matter doing anything else in the industry. You can only do so when you are famous or successful. But it is fine to think of artists being electricians, technicians, teachers. If you want to have a picture of artists in the industry, Pace Gallery organises an annual summer show of its own employees. I say this because they, that is the other people that populate our industry, would rather I write about them, for them, than make a studio visit. A friend in New York says that he does not write about living artists any more for that same reason. I cannot recall anyone ever coming to my art through my writing. But I have had a few visits from people through being a writer, although this has been extremely rare.

I did not intend to write. It is just that I have a second degree in history of art, and someone asked me to write something, and that led to another and so on. A decade later, you’re a critic. I emphasise “critic” rather than “art writer”. That genre of writing encapsulates a lot of things that includes journalism. The latter is not criticism, it is news. Valid but not useful. I think of criticism as a form of activism; you see, you report, you interpret, then offer opinion. There is a very fine example of this by the late Peter Schjedahl on Stanley Whitney in the New Yorker. It is one of their short reviews, merely eight lines long. And yet he achieves just this, and with gusto; genius. I think artists should write, if they can. We provide another kind of insight, and it is usually opinionated–a quality that I think we seem to be drifting away from. It cannot be criticism without opinion.

As for the second part of your question, I am not sure I navigate it well. I think I treat the writing seriously, rather than as a networking tool. I think some of us do that. I often think writing, for the reasons I have stated above, sets me at a disadvantage. On the other hand you have access. As someone who landed in the London artworld cold, it was very useful.

“I think artists should write, if they can. We provide another kind of insight, and it is usually opinionated–a quality that I think we seem to be drifting away from.”

Recently, I penned an essay reflecting on artist writings (texts written by artists). I am curious if you think artist writings should be considered its own “genre” or category unto its own, akin to how we think about art criticism, exhibition texts and art historical research? Is this delineation helpful/ productive?

Yes, definitely, but personally I am not fond of a lot of it. Sometimes it reads like pseudo-wise ruminations or obscure fun. Why not read philosophy like Jacques Derrida or writers like William Burroughs, Samuel Beckett or James Joyce, who work at the edge of writing. Maybe I have lived in the Anglo-American world too long. I think writing here has a direction, i.e. more linear, moving from point to substantiation… Whereas in Continental philosophy, i.e. Europe, writing is meandering, or circular till meaning becomes apparent.

There is definitely a place for artist writings. Many artists have logorrhea; I include myself here, so we should have a vent that is creative. Also our terrain is very often defined by others: critics, historians, theorists, and journalists(!?) so it is good to put a marker down. But if you are talking about an art form that uses the written word, why not? However, unlike other forms, it is required that you know that particular language. The beauty of the visual arts is that it is open, in theory anyone from anywhere can look at an artwork.

Personally I like Chris Burden’s notes to his performances–very dry. Jeffrey Vallance’s stories about his “adventures” read like amateur or folk anthropology , but are all absurd, hilarious and poignant. By the way, you should all read him. He is hilarious. Julian Schanbel’s autobiography, CVJ: Nicknames of Maitre D’s & Other Excerpts from Life, written age 36, that is at the peak of his fame, is a great read and should really be considered in this genre rather than autobiography. On his website it says, “often perceived as an early autobiography, but written by the artist as on-the-job training notes to share his experiences as a painter.” I won’t comment, but read it and see if you think it helps with your on-the-job training. I think there are exaggerated truths in it. But, hey, his life reads like an exaggeration…

As a painter, I enjoy reading painters on painters–but that is not artist writings. Sometimes what they do not say about themselves, they say about others. For myself I have no thoughts when it comes to inventing that sort of writing. It is all abstract to me!

Sherman Mern Tat Sam, ‘seen better days..’, 2022, oil on panel, 31.5 x 21.4cm. Image courtesy of the artist.

What has become easier or more difficult to do as time has gone by? You could anchor your observations through specific examples.

If you are a painter, I think it seems easier when you are younger. There is a lot of self-discovery then. As you get older, there are less discoveries, although I think that is when it becomes more interesting because you start to break new ground, but also more difficult. This is where you have to find your space and grow into it.

I think our “industry” has changed a lot. The first Venice Biennale I went to was in 1988. I saw Jasper Johns, Cy Twombly, Jannis Kounnelis in the main exhibition. Relatively speaking, we associate them today with–what we call–commercial galleries. I say “what we call” because I think the institutional world also has a kind of “commercialism”, in that they also need and collect money. They just use different vectors to get it. In England, that measure is “foot fall”. Yes, time has moved on and art has changed, but today I think there is a divide between what we consider gallery artists and biennial artists. Of course biennial artists have galleries, and every year the top hot things inevitably land in them. I think this divide has been created by the proliferation of biennials and art fairs, not to mention curators.

Right now, in 2023, there is a kind of “wibbly wobbly” figuration that is prevalent in galleries–the fashion in the Anglo-American art worlds right now, and figurative painting in general. So either you fall into that category or the biennial one - which is perceived as the “serious” art. The other tendency is towards a very worthy or virtuous type of messaging. In a way, all art is serious art, it is just a matter of where you place the emphasis. The virtue lies in the art, not the subject matter. From my point of view, the subject matter is merely the inspiration. I am making this very black and white. It is of course very grey with many exceptions. But what I mean is that there are thoughtful and interesting artists who do not fall into these categories and are often excluded… until they become fashionable, of course. I have said this before, but if I could embargo art fairs and biennials for a decade, I would. If you really want to know what artists are doing? Go to their studios and their one-person shows. Unfortunately, that means visiting their galleries regularly, for those who have them. A one-person show is an expression of considered thinking. The other things are expressions of dealers or curators.

Secondly, it feels like big business now, whereas when I started even the big galleries then felt like cottage industries.

“If I could embargo art fairs and biennials for a decade, I would. If you really want to know what artists are doing? Go to their studios and their one person shows.”

What do you think has been/is your purpose? Has your purpose remained steadfast or evolved over the years?

Hahaha.. This is a trick question, right? When I was a student, I set out to make great art. That is still what I want to do. The question is, and it is always the question, what is great art? I think this is where things change. Or I have changed. I think that idea or ideal evolves as time goes by. Everything else is negligible.

Sherman Mern Tat Sam, ‘Heaven must be’, 2022, oil on panel, 28.7 x 15.9cm. Image courtesy of the artist.

Could you talk about current/upcoming projects?

At the moment there are two forthcoming shows. As you may or may not know, I am a very slow painter. Things can take years to come to fruition. So I do not talk about projects or even groupings of works. Things overlap, ideas seep from one work to another. Both these shows will contain groups of works from a range of years.

They are both two-person shows. The first is at Kingsgate Project Space in West London this September with Alice Walter, a playful young painter, who is based in Bexhill-on-Sea. It is part of a year-long series of painting exhibitions. Dan Howard-Birt, who is the director and also a painter, has instigated a series of pairings; some with artists who are friends, and others, like this one, by bringing two artists together.

This will be followed in January 2024 with a show at Mamoth Contemporary in London. It is with Nancy Shaver, a wonderful septuagenarian artist based in Hudson, New York. Nancy makes a kind of assemblage, so I think the show will be paintings of mine interspersed with her floor pieces and a few reliefs, which she calls “Blockers”, constructed from blocks wrapped with fabric.

I think there is a bricolage sensibility that runs through the three of us, and a sense of play. The characteristic of playfulness is what I think runs through our works.

And finally, what would be a key piece of advice to young art practitioners that they can learn from to apply to their own careers?

Haha.. I like that you think I am successful. It certainly doesn’t feel like it. But I think it is human to feel that we can be better off. Giving advice is hard. We work in an idiosyncratic “profession”. Each person finds their own route, and no two roads are the same. No two people get lucky the same way. There is no corporate ladder…

First off, I think everyone should try to see art better. Emphasis on see. Today, I feel that people read art rather than see art; it takes a while to see something, so sometimes many glances are required for the work to percolate through your brain. And then many more glances before the words that are in your brain clear out of the way of the object. Try not to read the press release. The information does not lead you to the art, despite what the artist, gallerist or curator might tell you. We live in a time where we talk the “about”, I am more interested in the “is”. Conversely there is a fashion for art today that is made to be read–essentially a kind of graphic design with conceptual perfume. When I am in France, I call it “bijoux conceptualism”. Even then there is still an “is”.

Secondly, I think you should all be aware that there are many artworlds. There is a kind of international artworld, partly defined by art fairs and biennials, and a local one. Artists of course cross over both. But there are some artists who are very local, and known only to those who are there or some lucky visitors. Of course, international artists are also local ones. To pick an obvious example, Ed Ruscha is a quintessentially LA artist, yet is also a very big name internationally. Since the 1990s, the artworlds have become more international, via cheap travel and, latterly, social media. Also artists are diverse, much more than institutions, survey shows, magazines and media make out. The buzzword is “diversity”, but notice how they all look the same? There is always some weirdo somewhere in the world, burrowing deep and creating some wonderful eccentric things that will inevitably force us to change our view of the world.

Which leads me to the third point: try to see as much art as you can–in the flesh. I meet lots of artists and art workers now who know a lot, but it is always through the internet or social media. There was a running joke in the 1970s in New York about the art coming out of LA–the light and space school–that it was shiny because they were looking at art magazines which were all printed on shiny paper. I think today there is a kind of instagram-friendly version of that effect.

If you are a young artist today, the world is your oyster. You cannot see it when you are young, but the art world is ageist. It is interested in you if you are young or old. Maybe when we are young, we are more brash, or is it because the prices are lower? I do not know. I think there is this idea of discovering a bright young talent as well. I know so many curators that are interested in discovering the next young thing–and they like it more if this young thing is from another country. If you are a young artist and no one is interested yet, do not worry. You will just become a juicier steak for the future.

Try to live somewhere else for a time. I mean another country, preferably one where you do not speak the language, and not as a student or at a residency. I know this is very difficult. But sometimes when there is nothing behind you and nothing ahead of you, there are real discoveries to be made. All our job is on-the-job training; you make, you learn. There is no short cut around this. So get started! And keep going! I think the people who succeed are the ones who are able to recognise their situation. In this I mean you work with the means or temperament at your disposal. For example, if you have very little time and no space, then you have to make do with, say, an hour a night at your kitchen table before bed. Or if you have very little money for your grand installations, you have to figure out how to make something out of nothing. Look at early Robert Rauschenberg. If you do not have the temperament of someone who has to touch their artwork a thousand times, realise that sooner rather than later. Do not be tripped over by what you think your art should be, and realise what your art can be.

I think it helps if you see this as a life, rather than a career or profession–at all levels. There is very little money in it. Well, there is a lot of money but it is not very evenly distributed. Look at the current actors and writers strikes in Hollywood, an actor said that after he factored all his expenses he was working at a loss. Think of our work that way, if not more so; at least when you act you are paid for that. So if things are rosy, don’t act like an ass. Things change quickly. If you can find a simple low-maintenance job that you do not mind, which helps things tick over, keep it as long as you can. Curators, that does not mean slacking off as a bureaucrat in an institution and drinking the cheap booze!

Finally, to work in our industry, at all levels, you have to have very thick skin or lots of backbone. If you need to be constantly told how wonderful you are, or cannot take no for an answer, go work in Hollywood. At least I imagine that that’s where they blow sunshine up your ass.

‘Alice Walter, Sherman Sam’ is on view at Kingsgate Project Space in London, from 22 September to 14 October 2023.

Access the full Midpoint series here.