Conversation with Abhijan Toto

The Forest Curriculum, GAMeC, Subhashok Arts Centre

By Ian Tee

Abhijan Toto. Image courtesy of the Forest Curriculum.

Abhijan Toto is a curator and co-founder of the Forest Curriculum. Established in 2018 with Pujita Guha, it is a multi-platform project for research and co-learning around naturecultures of zomia, the forested belt that connects South and Southeast Asia. Abhijan has worked with the Dhaka Art Summit, Bellas Artes Projects (Manila) and Council (Paris), and was awarded the 2019 Lorenzo Bunaldi Prize at the GAMeC, Bergamo.

In this interview, Abhijan talks about the Forest Curriculum's indisciplinary — as opposed to interdisciplinary — approach to artistic research, the ethics of collaboration and his first project as curator at the Subhashok Arts Centre (SAC) in Bangkok.

Pujita Guha. Image courtesy of the Forest Curriculum.

I'd like to start by asking how you met Pujita? And are there specific conditions The Forest Curriculum is responding to?

Pujita and I have known each other for a long time, because we were from the same hometown and moved in a lot of the same circles. The forest curriculum came about when we reconnected during the student protests in the Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi. I traveled there as part of a contingent of students to support the movement, as an act of solidarity. We were sitting there in that context, listening to these speeches and questioning what the nation state is right now. We started the conversations that would ultimately lead to the Forest Curriculum.

For us, it was never about making exhibitions, nor was it about participating in the art world in ways that we have become overly accustomed. Instead, we are always looking at ways to leverage on the infrastructures and frameworks within which we are forced to operate in and move towards another form of engagement.

This structure is informed by my time working for Council in Paris, which is a curatorial collective founded by Grégory Castér and Sandra Terdjman. Terdjman also co-founded KADIST. They pioneered this form of curatorial practice called the inquiry, which focuses on a specific group of artists and geography, looking at the ways in which artists can intervene and create situations around specific subjects. The first project I worked with them on is The Against Nature Journal, which started as a response to colonial penal codes that criminalise "acts against nature", such as Section 377 in the Indian and Singapore Penal Codes. We worked with legal agencies in different parts of the world to challenge such laws on a legal basis, and think about what nature means with regard to the law. It's lovely to talk about this right now, because the first issue just came out.

In a strange way, art is obsessed with contemporaneity and speed, but at the same time, it allows for certain things to happen over a long period. We are used to artists being like, oh I've spent 10 years on this and I'm so conditioned to continue to work on it. This is very different from academia, wherein one is constantly able to produce new engagements and move into different directions, and create an open situation that pulls the world in. We were thinking about these forums together when we launched the Forest Curriculum. It can act as an institution, a framework, a collective, or whatever it needs to be when occupying a particular space and responding to it.

In your essay 'Notes Towards Imagining a Univers(e)ity Otherwise', you wrote about artistic research as a model for indisciplinary thought. What does "indisciplinarity" entail, as opposed to terms like "interdisciplinary"?

Essentially, the essay was talking about Forest Curriculum. One way to describe it is the first draft of a future University, thinking more from the perspective of the undercommons. The idea of indisciplinarity came about through conversations with our colleague, Jessika Khazrik, was mentioned in the essay as well. When we talk about interdisciplinarity or multi-disciplinarity, it still foregrounds an existing disciplinary structure to which we are making mere amendments or supplements to. This plays out across the formation of institutions like middle schools, labs and study centers, which then become reified into universities. We are interested in looking at ways to interrupt this form of knowledge circulation and ask what power structures give us these disciplines.

Hence, we foreground this idea of artistic research as a way of moving from practice towards other forms of circulation and research. We also wrote about indigenous thought as an alternative to the anthropocentric worldview. Artists and filmmakers in Southeast Asia were already doing this, even though their artworks are seen as objects rather than methodologies for framing thought. For example, Apichatpong Weerasethakul's 'Uncle Boonmee' (2010) can be taken as not just a film, but rather as a series of proposals that can be enacted in other forms as well. This is how we can look at indisciplinarity as the thing that gives form to these modes of working with artistic research.

“Therefore, when we talk about responsibility, it is precisely thinking of how to work and think with, as opposed to about, as the fundamental mode of being.”

How does this mode encode forms of responsibility into the process of knowledge production?

This responds to questions of extractivism which is fortunately gaining more currency within academic and artistic discussions. The way we approach it owes a lot to contemporary anthropological discourse, such as the work of Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, looking at how to invent forms of circulation and production which are not extractive. A fundamental dismantling of disciplinary form is crucial to us being able to do this, because these disciplines are built on certain logics of extractivism, via their histories of colour within colonialism and imperialism. To move within disciplinary form is to perpetuate such extractivist forms of being. Therefore, when we talk about responsibility, it is precisely thinking of how to work and think with, as opposed to about, as the fundamental mode of being.

We are also referencing the work of our colleague Erik Bordeleau, who is a philosopher of finance, and experiments with reengineering financial capitalism as a liberative force. It has to do with structurally changing the relationship between knowledge and value, such that it belongs to all of us instead of a select few. Through our work, we began to see mirroring between the bank and the university, as well as the ways they are entangled.

The Forest Curriculum's Summer School in Bangkok, 2019. Image courtesy of Luthfan Nur Rochman.

The Forest Curriculum has collaborated with a number of institutions and organisations. How would you qualify or frame a successful meaningful collaboration?

Collaborating comes from with others. Therefore, it is always a negotiation borne out of working in a space that belongs not only to us. Fundamentally, we look for mutual stake holding, by asking what the stakes are for those who come into conversation with us and the ways in which cultural capital is distributed via collaboration. An example would be the heavily criticised IdeaCity festival at NTU CCA in Singapore earlier this year, a platform funded by Goldman Sachs and supported by the New Museum coming into Southeast Asia with this kind of extractivist modality. This premise seems like an odd kind place for us to be. However, the curator Vere van Gool placed a huge amount of trust in us to not do anything in Singapore and instead we went to our community in Los Bānos, Philippines, and created an engagement there.

Coming back to this point on the redistribution of cultural capital, it's important that things go out of our hands so situations can emerge on their own. When we ran the 2019 Summer School in Bangkok, all sorts of beautiful projects, collectives and even new romantic relationships formed as a result of spending a month together. The programme drew in participants from various backgrounds, from club kids to academics and activists. It was a space for sharing time and energy together. So when we talk about a successful collaboration, it is not just about us collaborating with an institution, but rather creating an overall collaborative environment where many things can happen organically.

“Fundamentally, we look for mutual stake holding, by asking what the stakes are for those who come into conversation with us and the ways in which cultural capital is distributed via collaboration.”

Speaking about the Summer School programme, the second edition was supposed to happen in August 2020.

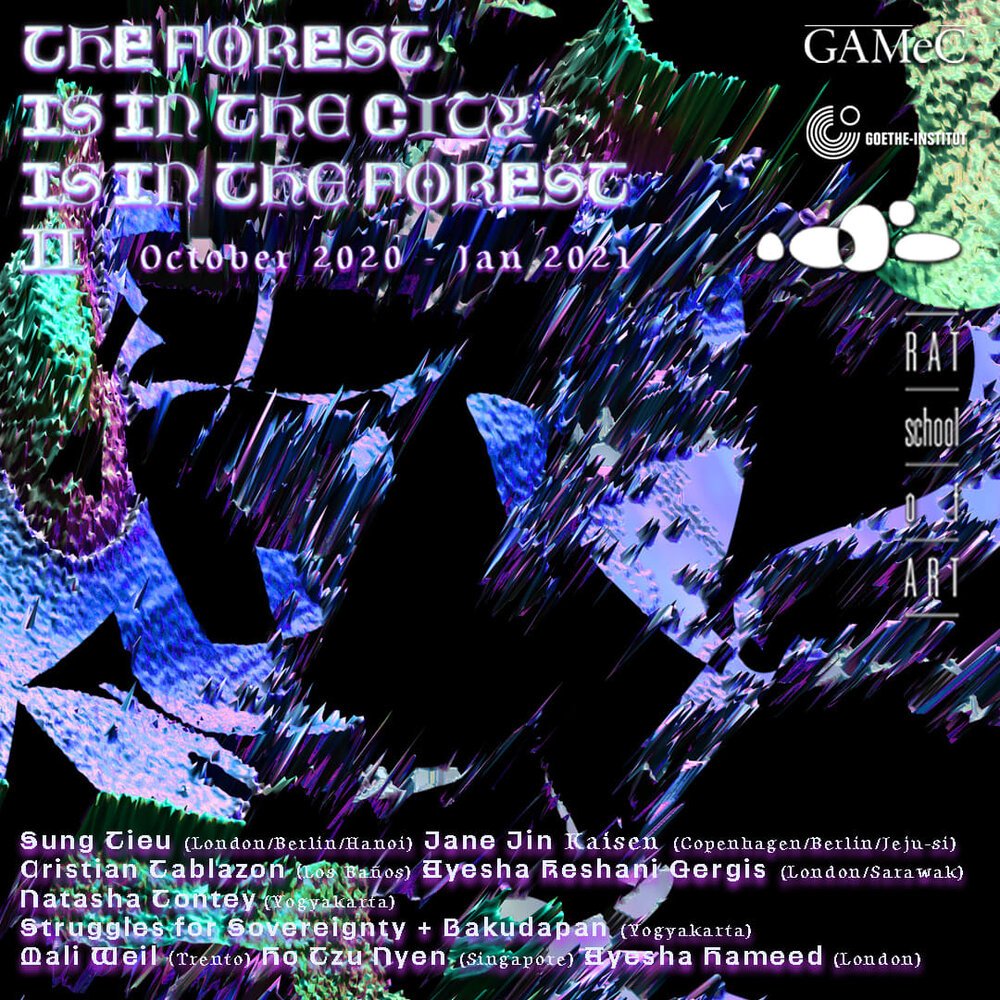

One of our longtime collaboration partners has been Mijoo Park, who runs the RAT School of Art in Seoul. We were supposed to work with her on the summer school and organise a programme in Jeju Island, Korea. Due to the current pandemic situation, it has evolved into a series of online talks happening over four months, involving collaborators we have known for some time and participants from the last summer school who are returning as speakers. The series will start on 13 October 2020 and goes on until the middle of January 2021.

It is also a great opportunity for us to invite people that we would otherwise have had a difficult time flying into the region. For example, one of the first speakers is going to be the Danish-Korean artist Jane Jin Kaisen, who was one of the artists exhibiting at Korean Pavilion in the 2019 Venice Biennale. We see it as a continuation of the programme I mentioned earlier in Los Bānos called 'The Forest is in the Cities in the Forest'. We are thinking about what it means to occupy the space of the forest right now, but not also drumming on about the pandemic.

Visit to the Rabor Zoological and Wildlife Collection as part of ‘The Forest Is in the City Is in the Forest’, a two-day workshop in Los Banos. Photo by Mijoo Park, image courtesy of Nomina Nuda.

The Forest is in the City is in the City – II, public programme curated by The Forest Curriculum and hosted by RAT Projects in Seoul.

How are you two sustaining your respective practices? Is there a piece of advice you were given or a lesson learnt you could share?

People always ask us: how is Forest Curriculum funded? How do you continue running this? And there's a very simple answer, which is that we're very poor. We have been lucky to receive funding for certain individual programmes, but there haven't been any structural grants that entirely supported us. We are also fortunate to have friends and supporters who are constantly on the lookout for us. Recently, a friend of ours Kai Altmann (Hityasha) nominated us for a COVID-19 relief grant. Even though it's not a large sum of money, it means a lot in our situation when we are already struggling and our programmes are being cancelled.

I do not like the word advice, but I think that it is important to gravitate towards people who are as deeply invested in the ideas that you are working on. It creates conditions to work together and solve problems, whether it is finding a couch to crash on or some money to invite some speakers over.

I think that a lot of this came from my time working at the Dhaka Art Summit in Bangladesh, which is a logistically challenging country. Looking from the outside, it seems like a private foundation with unimaginable resources at its disposal, but you will be surprised by how much of the exhibition is actually carried in on backpacks into the country. We like to call it a zomian attitude of continuing flows and finding different channels. That is how we approach and structure the way that we work.

Exterior view of Subhashok Arts Centre, Bangkok. Image courtesy of Subhashok Arts Centre.

‘There is no Thai Park’, 2020, exhibition installation view at SAC Gallery. Image courtesy of Subhashok Arts Centre.

You recently joined the Subhashok Arts Centre (SAC) in Bangkok as a curator. Could you talk about your work there?

SAC was founded by Subhashok Angsuvarnisiri, a prominent Thai collector. Today, it is a very significant gallery in Bangkok, which has been doing the work of supporting some great practices in the city. I joined the SAC team this year at a very exciting moment when Jongsuwat Angsuvarnisiri took over as the new director. It was through conversations with him and hearing his vision for the gallery that prompted me to want to work with them.

I think SAC has great potential in what it can offer to the Thai art scene. We are already seeing galleries such as Bangkok CityCity and Nova Contemporary that are expanding what we tend to think of as a traditional gallery. In that vein, SAC is an institution with a gallery, art and design labs, a residency program and a conservation center. Thus, my colleagues and I are creating a programme that speaks to a wide variety of interests, as opposed to merely acting as a commercial gallery.

The first show I am curating is titled 'There is No Thai Park', realised with the un.thai.tled collective in Berlin, comprising Thai diasporic artists, filmmakers and creatives. This show looks at the history of the Thai park in Berlin, which was started by Thai women as a Sunday picnic spot to find community and it turned into this huge outdoors, Asian street market. It had a significant impact on the ways in which Asian identity was constructed in Berlin. The un.thai.tled collective produced a lot of documentation of the park itself, and of German media coverage over its 20-year history. We are thinking about what it means to engage with those histories from Bangkok, where there's a totally different tenor and framework to understand marriage, migration and diaspora cultures.

This is the first project emerging out of a long-term inquiry into Thai diasporic creative practices as well as the larger question of Thai identity and the entangled narratives that go into producing it.

'In The Forest, Even The Air Breathes', 2020, exhibition installation view at GAMeC, Bergamo. Presented as part of Premio Lorenzo Bonaldi per l'Arte - EnterPrize, 10th Edition. Photo by Lorenzo Palmieri, image courtesy of GAMeC - Galleria d'Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Bergamo.

The latest project emerging out of the research you have been doing is 'In the Forest, Even the Air Breathes' at GAMeC, Bergamo. It consists of an exhibition and a series of five publications produced in collaboration with RAREditions. How do the two components relate to each other and what do you hope to get out of the project?

To provide some background about the exhibition, 'In the Forest, Even the Air Breathes' is organised as part of the 2019 Premio Lorenzo Bonaldi prize which I was awarded. As you mentioned, the exhibition draws from the research we have been doing and is a kind of bookend to this phase in our practices. It moves within three key themes: natural history and the representation of nature; histories of violence and issues of occupation; as well as the relationship between tales of the spirit and the world of humans.

As for the publication project, they are in dialogue with the exhibition but not explanatory pieces. Each contributor goes into totally different trajectories. For instance, Pujita wrote about opium while Cristian Tablazon delved into the church's construction of natural history during the Marcos regime. Wong Bing Hao dealt with trans-ness as a kind of organisational principle.

Going back to the idea of stake holding and successful collaborations, when we work with an institution outside of the region, we always ask: how is this going back to the people in our community? How is this not just a shiny catalogue and an exhibition for a couple of white people to see? We use this money to fund research on topics that people have been dying to do but have no access to resources for. We also use this space to talk about issues that are politically sensitive in their own countries. These considerations take shape in the course of our conversations and we began to think about them in an indisciplinary vein by tying together different methodologies and approaches.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

'There is No Thai Park' is on view from 24 October to 29 November 2020 at SAC Gallery, Bangkok.

'In The Forest, Even The Air Breathes' runs from 1 October 2020 to 14 February 2021 at GAMeC, Bergamo.