Conversation with Singapore artist Jimmy Ong

Negotiating home, sexuality and community

By Ian Tee

Jimmy Ong (b. 1964) is a Singaporean artist best known for his large scale, figurative charcoal drawings on paper, marked by a distinctive fleshy quality. He came into prominence in the 1980s, with early works that focused on sexuality identity and gender roles in the context of the traditional Chinese family. Now based in Jogjakarta, Jimmy's projects interrogate the colonial figure of Stamford Raffles within Javanese history. His key exhibitions include 'From Bukit Larangan to Borobudor' (FOST Gallery, 2016), 'SGD' (Singapore Tyler Print Institute, 2010) and 'Sitayana' (Tyler Rollins Fine Art, 2010).

We speak to Jimmy on the occasion of his new solo presentations: 'Poverty Quilt/ A Year in Java' at the Asian Civilisations Museum (ACM) and 'Visual Notes: Actions and Imaginings' at NUS Museum. In this interview, he talks about the premise behind both exhibitions, Singapore art scene in the 1980s, and how growing up as a gay man informed his work and outlook.

Jimmy Ong, 'A Year in Java', 2019, exhibition installation view at the Asian Civilisations Museum. Image taken by Ian Tee.

I'd like to begin this interview discussing your new show at ACM. Can you share more about the exhibition's title 'Poverty Quilt/ A Year in Java'?

Poverty Quilt come from the idea that "there's purity in poverty", a Taoist sentiment I felt most acutely this year. The poverty also refers to my grandmother’s year of economic independence as a seamstress when my grandfather was stranded in Java. The work in ACM is more of a patchwork than a quilt, involving a group of assistants and artisans I have come to depend on. It's a social relation that's based more economics than aesthetics.

'A Year in Java' refers not only to my grandfather's and my time spent in Java, but also points to the year Raffles was missing, soon after founding Singapore. It is the very year, two centuries ago, which we are celebrating now. My grandmother would be 100 this year if she's alive, and that's something to celebrate too.

Jimmy Ong sewing buttons onto 'A Year in Java', at the Asian Civilisations Museum. Image taken by Ian Tee.

When we last met, the work exhibited at ACM was still in progress. It was at Waterloo Street where you invited people to contribute and sew a button or two to help finish it. The exercise was a test-run of sorts, to figure out how audiences might respond. What insights did you glean from it and were there any changes you've made to the set-up after?

Thanks for coming to help during the test run. The opportunity came up because the space was sponsored by a sports shop. I didn't quite make it as public as the attendees were mostly my friends. I had just returned from the US after hosting a memorial for my husband who passed away. And it was moving that all my Singapore friends turned up at the test run for what seemed like a secret memorial.

A few of them brought buttons from their late mothers so what struck me was the idea of private memorials in public spaces… It is done in the presence of others, a necessary element for grieving. So after the test run I just knew that I needed to mirror such private memorials against a national commemoration. I have added a sewing performance which calls for participants to perform a wake.

Jimmy Ong and Han Chung, 'Covered Causeway', 2019, presented as part of OH! Open House 'Passport'. Image courtesy of OH! Open House.

This shift towards creating artworks with a participatory element is a relatively new development in your practice. What is driving this new direction? Is it related to your explorations in performance?

The drive is two-fold. I kept hearing how it is easier to get state support with “community interactive projects”, although I hadn't really applied for any grants in last 30 years. At first, I thought it would be a social relational work so I kept the door open to try to involve the community.

Subconsciously, I also think I am emerging from a long slumber of being isolated from people. Moving from the United States to Indonesia provided the chance to break that habit of privacy. It seems performance allows artists to do what they cannot in real life. And lately it's becoming more urgent for me to relate and share beyond the mundane.

I am also thinking of 'Covered Causeway' (2019) which was an "experience" you and your host Han Chung developed for OH! Open House this year. Could you talk about the process behind this collaboration and the questions it hopes to provoke?

The process hinges on trust and letting the conditions and materials direct you. We both got paired off in a perfect storm of a situation. It was liberating for me as I found out how the audience shared so many of the questions I have about making choices. They were mostly about where one chooses to live versus which country one calls one’s own.

'Visual Notes: Actions and Imaginings', 2019, exhibition installation view. Image courtesy of NUS Museum.

Currently, the NUS Museum is exhibiting your early sketches, paintings and photographs in the prep-room presentation 'Visual Notes: Actions and Imaginings'. These are drawn from a shoebox of archival material you've donated to the museum, which also includes some personal effects such as postcards from your time abroad. Why is it important to you that this archive is in a public institution? Are there specific reasons why NUS Museum?

My initial thought is to try to get a collector to buy the entire lot of studies for larger works for the museum, so that I can have some money. The shoebox of materials was secondary to the collection of drawings and sketches, but I was too "sayang" to destroy them.

Then NUS pointed out to me how the photographs and postcards were more interesting to them as clues to the 80s when there was hardly any young artists in Singapore. I picked NUS because they accepted Ng Eng Teng’s lot of small sketches and marquettes, or "unfinished" works that have more teaching value than art market collectability.

Jimmy Ong, 'The Children of', 1987, exhibition view at Arbour Fine Art Gallery. Image courtesy of the artist and NUS Museum.

You had your first solo exhibition at Alliance Francaise in 1984, which was followed by other one-man shows at Arbour Fine Art Gallery, Art Forum, Goethe Institut and Cicada Gallery in Singapore. What was your experience navigating the market and gallery system at the time?

There were fewer art galleries in those days. It became a matter of whose nest I could put all my eggs in, as I was adamant about not being involved with the art market. I guess I was lucky being one of only a few artists in the 1980s. Everyone knew each other, so things just fell into place. I would not know how to begin as a young emerging artist now.

Who else were showing their works at these galleries and do you recall any memorable exhibitions from that period?

Two artists stayed on my mind: Wong Mei Sheong who also showed at Arbour Fine Art and Ho Soon Yeen's exhibition at the Substation. They both happen to be women artists.

You've exhibited together with Wong Mei Sheong in the 1980s. Could you speak more about what drew you to her practice and your relationship? I recall a two-part show 'Transfiguring' (2011) at The Private Museum which revisited works made in that period. You are both artists who worked from outside Singapore.

I met Mei Sheong 2 decades later in Singapore, only to know that she stopped painting since she married and had been busy raising children in Australia. I felt compelled to ask her if we could do a “Two Women Show”, hinting at my own domesticities. We have since become friends.

Jimmy Ong, 'Heart Sons', 2004, charcoal on paper, 216 x 126cm. Image courtesy of the artist and FOST Gallery.

Henri Chen was a mentor to you in your formative years as a young artist. You also spent a lot of time at his studio, talking and hanging out with friends till late. Who were at these gatherings and were there older artists you felt connected to?

The curator Choy Weng Yang and Taiwanese artist Yu Peng were there often, and Pan Shou was the oldest artist. There's also a sensitive writer named Tan Siew Kia who has fallen off the grid.

Could you share a piece of advice from Henri that remained with you?

That one should cherish time with friends? Circumstances can change one’s proximity to them quickly.

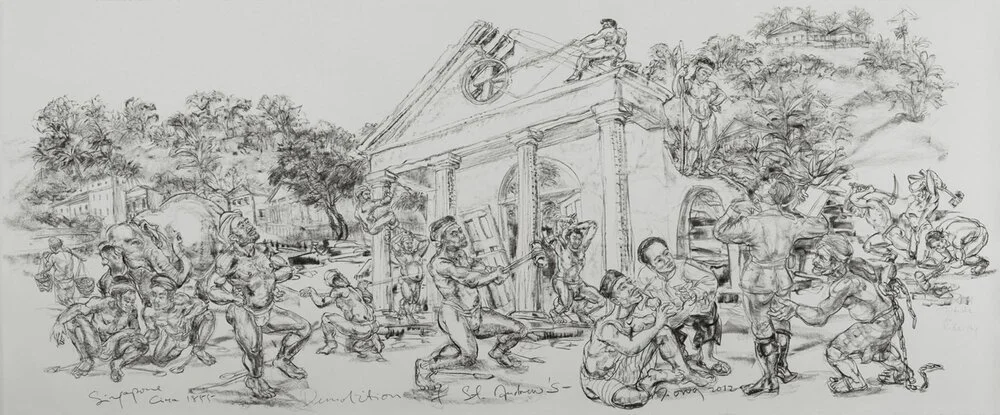

Jimmy Ong, 'Demolition of St Andrew's', 2012, charcoal on paper, 128.5 x 309cm. Image courtesy of the artist and FOST Gallery.

In your interview with Shabbir Hussain Mustafa ('Recent Gifts', NUS Museum), you mentioned that in the 1980s, you were "spending most of the time coming out as a gay man rather than being an artist". I want to ask you about the social climate for queer people in Singapore at that time. Were your friends also art practitioners? And what gave you the confidence to come out publicly in the newspaper in 1990?

My confidence came from gay friends such as Ivan Heng and Alan Seah whom I hung out with during National Service. Later, I met Russell Heng, Joseph Lo and more through 'People Like Us' in the early 90s at the Substation, which seemed like a homecoming. The Substation was an eye opener for me with so many like-minded people gathering to help ourselves. We were not just educating each other about coming out and safe sex, but also our rights as citizens when dealing with the police. That was the time of police round-ups at gay bars and clubs, and plain-clothes police entrapments at Fort Road.

The Straits Times has always censored my interviews as a gay man. The last one was a lengthy full page feature in 2011 about my family. Details about about my domestic life as a gay spouse in the USA was omitted, such that only half of the interview remained. The heavily edited article made me sound whinny as opposed to being celebratory about the domestic bliss I found.

In your interview with T.K Sabapathy ('From Bukit Larangan to Borobudor'), you described 'Demolition of St Andrew's' (2012) as a seminal work which spoke to Christian homophobia in Singapore. These are sentiments you've considered "personal up to this point". I'd like to ask what provoked this shift for you? And are there issues which you would not address in your art?

I think I was making 'Demolition of St Andrew's' around the time of AWARE Saga and when City Harvest Church’s congregation was at its peak… That's a whole decade ago.

I am certain there are issues which has yet surfaced for me or ones I have not to learn about.

Jimmy's studio in Jogjakarta, with assistants working on soft sculpture effigies of Stamford Raffles. Image courtesy of the artist.

You have a studio in Jogjakarta now where you began employing assistants who help you with your community projects and textile works. In this interview with Portfolio, you spoke about how for the first time, "your work involves another person's livelihood, that if you stopped working, this person will go hungry the next day". You were also reflecting on growing old, getting sick and dying.

I have changed my mind about being always able to make a living off one’s artwork alone. Short of asking for a handout from the state, individual artists will not always be economically independent. Nevertheless, I think the state should look after its artists when they are no longer useful, or young. But the true creative will always find joy creating, not always for money, so there's nothing to despair about.

What does home mean to you today? Has that sentiment changed over the years?

I am still working on this (smiles). I know I have left home. Twice now.

'Poverty Quilt/ A Year in Java' is on view from 20 September to 17 October 2019 at the Asian Civilisations Museum Singapore; while 'Visual Notes: Actions and Imaginings' runs till 31 December 2019 at the NUS Museum.

Jimmy Ong's recent works are included in the group exhibition 'In Its Place' at FOST Gallery, which is on show till 10 November 2019.