How Have Artist-Founded Galleries Engaged with the Market?

Approaches for long-term sustainability in Southeast Asia

Use Your Illusion, 2020, installation view of group exhibition curated by Zarani Risjad. Image courtesy of Edwin's Gallery.

Following 'Why Have Artists Started Independent Spaces and Galleries?', which delved into the history of artist spaces in Southeast Asia and how they impact their founders' artistic practice, this article focuses on the economics of keeping them afloat. It looks at how artist-founded galleries have engaged with the market and considers the question of long-term sustainability.

Edwin's Gallery presentation at the inaugural Art Basel Hong Kong 2013.

While artist-led spaces tend to favour more experimental works, one would be remiss to think that all of them shy away from commerce. Edwin Rahardjo and Chua Soo Bin are two veteran artist-gallerists who have held leadership positions in their respective art scenes and shaped local art markets in their infancy. Rahardjo is the owner of Indonesia's oldest gallery, Edwin's Gallery (1984-present), and currently the chairperson of the country's gallery association; while Chua is the founder of SooBin Art Int'l (1990-present) and the fair director of ArtSingapore from 2000 to 2002.

Tapping into their networks in wider Asia, both of them introduced Chinese contemporary art to the Indonesian and Singapore markets in the 1990s and worked to promote local artists abroad. "I met Johnson Chang from Hanart TZ Gallery in Hong Kong through seminars, and he recognised the work we do in Indonesia," shares Rahardjo. "The gallery's reputation in promoting young Indonesian artists allowed these doors to be opened quite easily." Entang Wiharso, Heri Dono and Christine Ay Tjoe are among the celebrated artists Rahardjo supported with exhibitions at his space or collaborations with institutions and international galleries. Today, Edwin's Gallery continues to showcase the work of the next generation of emerging artists such as Meliantha Muliawan and Gabriel Aries.

Soler Santos, founder of West Gallery. Image courtesy of West Gallery.

Mariano Ching, Today, 2020, exhibition installation view. Image courtesy of West Gallery.

At times, the generosity of established artists is needed so that younger generations of artists can gain a foothold. Soler and Mona Santos started West Gallery in Manila (1989-present) with a space offered by Soler's late father Mauro Malang Santos (Malang), who is an acclaimed cartoonist and painter. The gallery was created in response to the lack of exhibition opportunities for emerging artists, and was sustained by Malang's works until the mid-2000s when the local market for contemporary art started to pick up.

Recalling the Philippines art scene in 1989, Soler says that it was a time when senior artists dominated the market even though there were many working young artists. "I met Roberto Chabet when I was studying fine arts at the University of the Philippines. He was my professor and eventually, a very good friend," he shares. Chabet would receive four to five exhibition slots every year to show works by his students at West Gallery. In fact, the older artist was himself an initiator of Shop 6, an artist-run space in the 1970s. Looking back, Soler is proud that many contemporary artists from the 1990s who are well-respected today once exhibited at West Gallery.

Similarly, HOM Arts Trans in Kuala Lumpur (2007-present) has been instrumental in nurturing Malaysian young artists through their exhibitions, residencies and awards. The artist-run space was established by Matahati, an influential five-member artist group that came to prominence in the 1990s. HOM's Young Guns (2013-present) and Malaysian Emerging Artist Award (a biannual award presented since 2011) are two important prizes that have given recognition and international visibility to rising talents. Recipients of the Young Guns award include Seah Zelin (2013) and Yim Yen Sum (2016).

Manzi exhibition space and artist residency at 2 Ngõ Hàng Bún, Ba Đinh, Hanoi. Image courtesy of Manzi Art Space.

Art For You, 2019, an art fair organised by Manzi Art Space and Workroom Four. Image courtesy of Manzi Art Space.

In Vietnam, efforts to grow the local art market are spearheaded by female leaders in the industry. Manzi Art Space (2012-present), co-founded by Tram Vu, Giang Dang and artist-curator Bill Nguyen, is a hub for Hanoi's art scene. Since 2014, it has been collaborating with Workroom Four to organise 'Art for You', an annual art fair with artworks priced affordably between USD25 to USD900. The long-term project has seen positive results in attracting local audiences, with university students and young working adults making up the majority of visitors in its latest edition. While they might not be customers today, Tram Vu is optimistic that they could be in future.

Parallel to this development, The Factory (2016-present) in Ho Chi Minh City aims to build a network of supporters for Vietnamese contemporary art through its 'Glass Box' programme. Founded by Tia-Thuy Nguyen, The Factory adopts a social enterprise model, where revenue is fed back into running the space. At present, less than 20% of its overhead costs is covered by artwork sales. "The initiative was motivated by a realisation that the majority of buyers of modern Vietnamese art at auction are based in Vietnam," Nguyen remarks. By better informing collectors about the synergies between modern and contemporary Vietnamese art, she hopes it would garner more patronage for living artists. Each edition of 'Glass Box' focuses on a specific medium, with guest lectures and private dinners for The Factory's VIP community.

The idea to start a centre for contemporary art came to Tia-Thuy in 2015, and she sought the advice of artists Tran Luong and Dinh Q. Le, co-founders of Nha San Studio and Sàn Art respectively. Commenting on the difficulties faced by artist-founded spaces, she adds, "In my opinion, if artists start a space together, they must rely on someone else to manage it and raise funds. Otherwise, it is hard for them to survive longer than two years. When I think about the future of Vietnamese art scene, I think of an ecosystem, not just individuals." For her, that ecosystem needs local collectors who support contemporary artists, institutions and independent researchers who produce knowledge, galleries that support experimental practices, and artists who are able to focus on practising without having to work multiple jobs to earn a living and cover production costs.

The Factory team on opening night of Leaf Picking in the Ancient Forest by Võ Trân Châu' (left to right): Quỳnh Trần, Bill Nguyễn, Zoe Butt, artist Võ Trân Châu, Vân Đỗ, Uyên Lê, An Duy Ngô and Nhung Lê. Image courtesy of The Factory.

In order to remain economically viable, non-profit artist spaces turn to supplementary businesses as a means of diversifying their revenue streams. One common example is the inclusion of cafés and shops within their premises to bring people into the space. For the last seven years, Manzi has been sustained primarily through its café and art shop, with the exception of large-scale public art projects that required external funding. In Chiangmai, Angkrit Ajchariyasophon's eponymous gallery (2008-2016) located above his family's restaurant, was kept afloat by revenue from the food establishment. In addition to these side businesses, Torlarp Larpjaroensook shared that Gallery Seescape's financial autonomy was possible thanks to Besto Boy, a series of functional sculptures and lamps which he began making in 2009. The Factory charges a small entrance fee for its exhibitions and public programmes to cover administrative expenses.

Elevations, 2018-19, installation view of group exhibition curated by Erin Gleeson at Icat Gallery. Image courtesy of Icat Gallery.

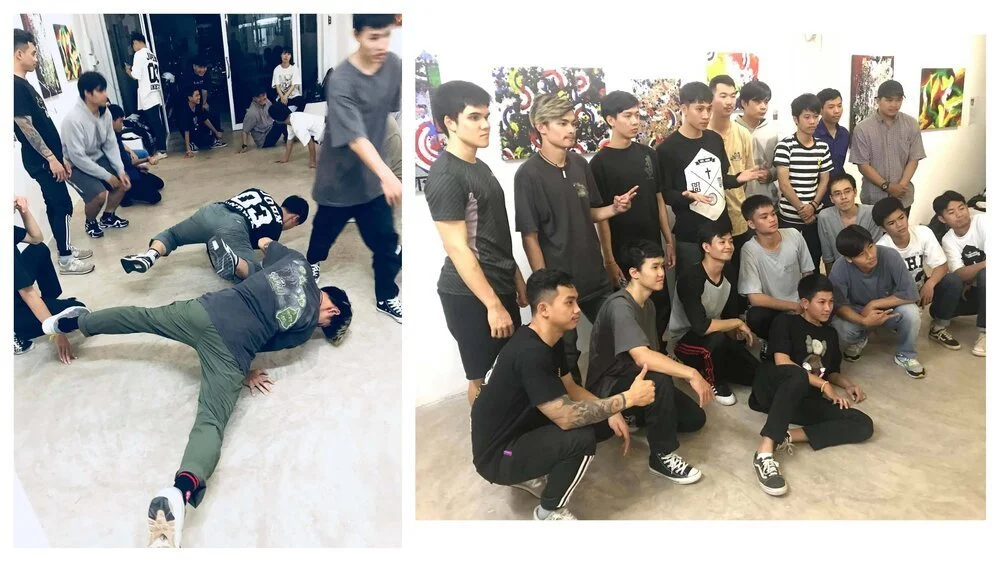

Powermoves and body control workshop by b-boy dancer C-Lil at Icat Gallery. Image courtesy of Icat Gallery.

Another source of financial support comes from grants and private donations. In 2018, Vientiane-based Icat Gallery (2009-present) hosted Elevations, a high-profile exhibition curated by Erin Gleeson which showed Southeast Asian. It was one of two international projects which supported the gallery with rental, refurbishment costs as well as payment for the gallery assistant. However, such private initiatives aren't sufficient to keep the space afloat. To keep rent affordable and to supplement income, Icat moved to a smaller venue and also opened the gallery for art classes, screenings and workshops. To date, it remains one of the few art spaces in Laos that exhibits a diverse range of works by artists living in the country, from drawings of traditional dancers by Souphalak Phongsavath to stop-motion animation by Souliya Phoumivong.

Laos’ political history also proves to be an obstacle for the art scene. Speaking about government regulations and censorship, Icat founder Catherine O'Brien comments, "I lived in Vientiane long enough to know that to survive, it was important to keep this low-key and local." She explains that the reluctance to support many artist-led activities partly stems from the fact that self-organisation outside of official groups was banned until recently. While international non-profit organisations have taken an interest in promoting cultural exchange in Laos, successful initiatives are few and far between and its benefits are often not shared by all groups. Against these challenges, Icat is sustained by support and ideas from its local community of artists and contributors.

Bale Project team. Image courtesy of Bale Project.

Exhibition installation view of SSAS/AS/IDEAS (2018), curated by Hendro Wiyanto. Image courtesy of Bale Project.

Like all ventures, the question of its lifespan comes up eventually and this could be associated with a plethora of concerns such as the founder's old age. In the case of Yayasan Selasar Sunaryo, a foundation established by Indonesian artist Sunaryo Sutono, starting a commercial gallery is envisioned as a means to ensure its longevity. Bale Project (2015-present) is a for-profit unit within the foundation, alongside Selasar Sunaryo Art Space (SSAS), Wot Batu, Cinderamata Selasar and Kopi Selasar. It handles projects ranging from commercial exhibitions to consultancy, as well as artwork commissions. "We want to develop and showcase the potential of Indonesian artists, from prominent old masters to young emerging artists," says Sunaryo. On top of supporting exhibition production, Bale Project also circulates artworks outside of Bandung through its collaborations with international galleries and its participation in fairs, such as Art Jakarta.

Entrance to Coda Culture's third space at 67 Aliwal Street. Photograph by Teck Lim.

Seelan Palay, founder of Coda Culture in Singapore, has a different position with regards to his gallery's lifespan. Since its inception in 2018, Coda Culture has moved twice to different locations when its one-year leases expired. Although the gallery has been able to sustain itself through artwork sales from the second year of operation, Palay insists on remaining agile rather than giving in to the pressure of longevity. "Remaining clear about the conditions that affect the lifespans of most independent art spaces, it doesn't matter if and when we have to close, but rather how much we can achieve before we do."

When asked about the future of artist-founded galleries, Palay remarks that they will always have a part to play, existing both within and beyond the market. For him, they are an integral part of the arts ecosystem as they give space to those who may not fit into one of the boxes defined by commerce or popular style. "They allow for the incubation of talented artists of all ages and backgrounds, and fosters horizontalism, which is important in a world that is so hierarchical."

Santos echoes this sentiment, though he worries that the impact of Covid-19 might affect the economy to a point where it becomes unsustainable for some spaces. As for West Gallery's long term goals, he says they will continue what they have been doing for the past 31 years, exhibiting quality contemporary art, encouraging young artists in their pursuits, and cherishing friendships with artists.

Jason Wee, founder of Grey Projects in Singapore, frames the relevance of artist-founded galleries as a question of spatial justice that applies beyond the arts. He asks, "Is any country or city considered optimal for growth when its markets are dominated by a small handful of large players, or is that a sign that monopolised influence will crowd out creativity? How equitable and democratic do you want your city or your scene to be?" Free spaces for experimentation, exhibition and engagement are essential for a diverse and healthy art ecosystem.

Across various contexts and stages of development in their art scenes, Southeast Asian artists have risen to the occasion to create independent platforms for personal expression. Artist-gallerists have led the way by providing opportunities to new voices and by finding innovative ways to keep these spaces financially viable. At times, their foresight and persistence contributed to the birth of a contemporary art market in their home countries. In today's climate where all galleries face unprecedented challenges compounded by the pandemic, it is worth remembering that culture exists because of the creative labour by artists. How they continue to work in different roles and impact their communities will be a testament to imagination and resourcefulness, regardless if the spaces they make are lasting or temporary, physical or virtual.

For insights on Southeast Asian collectives, artist-curators and the spaces they create, read Why Have Artists Started Independent Spaces and Galleries?.